Volume 10 Number 2

©The Author(s) 2008

"Fixing Puppets So They Can Talk": Puppets and Puppet Making in a Classroom of Preschoolers with Special Needs

Abstract

This article describes the ways in which puppets were used in two preschool classes of 3- to 5-year-old children with special needs in Indianapolis, Indiana. During their study of puppets, the children created topic webs, used and created different types of puppets, listened to guest experts, and participated in a workshop conducted by nationally renowned puppeteers. The article concludes with teacher reflections and the Indiana Foundations for Young Children that were addressed by the puppet activities.

Background

The Warren Early Childhood Center, where the activities described in this article took place, provides services for 340 children in kindergarten, preschool, developmental preschool, and developmental kindergarten. The school is inspired by the practices and philosophies of the Project Approach and Reggio Emilia. The walls are covered with children's transcribed conversations, photographs, documentation, and child-created work. The classroom environment is designed to create a warm atmosphere that encourages learning and creativity.

The children in my classes attend school 3 hours a day, 5 days a week. There were 10 children in the morning (five boys, five girls) and nine in the afternoon (eight boys, one girl). Their disabilities ranged from developmental delay to communication disorder to moderate mental handicap to multiple disabilities. In addition to direct instruction, the children received speech, occupational, and physical therapies. One of the boys, Ruben, spoke very little English at the beginning of the year.

This was my first year at the Warren Early Childhood Center, and my first year of teaching special education. When the school year began, many of the children in my classroom lacked the language skills many would consider necessary for a sustained study of any topic. However, as I listened to the children and observed them in action, it was possible to develop many projects from the children’s interests. Throughout the year, I saw their language abilities increase, along with instances when they showed initiative and took leadership roles, and I was impressed at the level of their engagement in investigations of topics—from shadow play to pizza to automobile repair to stained glass.

At the beginning of the year, the center’s director and I spoke about ways to promote language development. We talked about using puppets, but I had not made them available during the first semester. At the time that I decided to introduce puppets, the children had just completed projects on automobile repair and color with stained glass. Neither class had gotten involved in a new project, so I thought it was a good time to introduce some new materials for play. The children had also formed friendships and were playing well with one another. I thought that the puppets might provide opportunities for the children to interact more deeply with one another.

Emerging Interest

Introducing Puppets

The children’s involvement with puppets began with a small tub filled with store-bought puppets, which I placed on the floor during choice time. The initial puppets were purchased at dollar stores and were hand puppets or character bath mitts. I did not make any verbal introduction of the puppets, because I wanted to see whether the children might investigate them on their own.

In the afternoon class when the puppets were first offered, there was initially very little conversation among the children playing with the puppets. The class had nine children, but five boys primarily played with the puppets. Their play consisted mainly of aggressive actions, such as the puppets tackling each other. As they made the puppets tackle one another, the boys would yell, “Ahhh!” and “Get me!”

Figure 1. Nate and Brennan examine the store-bought puppets.

I allowed this type of play for a couple of days, waiting for a child to take the lead in expanding to a study of puppets. On February 11, 2008, I sat down with a group of the children who had been playing aggressively with puppets and used a different voice to make the giraffe puppet talk to them. I began with the simple introduction, “Hi, my name is Mrs. Giraffe.” I felt this introduction would allow the children to see how easy it could be to make a puppet talk; they would not need to make up an unusual name or a story line to follow.As I asked questions, all of the boys and girls responded to the giraffe puppet with puppets that they had selected.

Nate: I’m Duck.

Mrs. Servizzi: Hello, Mr. Duck. How are you doing today?

Nate: I’m getting Tiger.

Ruben: Get me, Ms. S.!

Mrs. Servizzi: Oh, Mr. Tiger, I want to be your friend. Would you like to play?

Ruben: Yes. Puppets friends.

Brennan (with the lion puppet): I’m Ruben.

At this point, Nate, age 3, began bringing pretend food—a cake and cookies—over from a dollhouse and offering it to the other puppets. Through their puppets, he and some classmates began to plan a party:

Nate (with a duck puppet): I’m having a party.

Brennan (age 3, with a lion puppet): I wanna come.

Nate: You bring the cake.

Nate to Ruben: You bring chips.

Ruben (age 3, with a tiger puppet): Don’t have chips.

Nate: You have to go to the store.

Brennan: I bring water too.

Boys: Mmmm, yum.

Introducing the Puppet Theater

I noticed that the children appeared to be giving the puppets a storyline, but they did not have a setting. On February 15, I brought a small commercially made puppet theater stage into the classroom. The stage was free-standing, with three shelves on the back for storage. On the side facing the audience were a red and white curtain, which covered the opening, and a chalkboard above and below the curtain.

As I had done with the puppets, I placed the stage at the front of the room and left it to the children to investigate. I did not tell them what it was or what they should do with it. The first children to look at the stage were Scarlett and Tommy. Both children have developmental delays, and Tommy has been diagnosed with a communication disorder and is very hesitant to speak in front a large group of children, though his speech is intelligible:

Scarlett (age 4): What is it?

Tommy (age 3): For puppets!

While Scarlett and Tommy looked at the puppet stage from all angles, their curtain discussion began. Although this exchange was mostly nonverbal, it was an important part of the inquiry. The children were debating whether the curtains should be open for the show or whether they should be closed, with the puppets sticking out from underneath.

Figure 2. Tommy and Scarlett explore the puppet stage.

Figure 3. Tommy tries a puppet show with the curtain closed.

Tommy, who was the more reserved child, preferred to have the curtains closed. His perspective changed, however, after he asked Ms. Sue, an instructional assistant, to do a puppet show. Ms. Sue made up her puppet show on the spot to demonstrate some of the play possibilities, sitting with three of the students in front of the puppet stage while two others moved in front of and behind the stage. The children seemed to be eageraudience members.

When Ms. Sue was finished with her puppet show, Scarlett and Tommy performed the first student-led puppet show. Scarlett used giraffe and frog puppets, and Tommy used a hippo and a bookworm. Scarlett’s puppets sang as Tommy opened the curtains and asked other children to clap. Scarlett made her puppets sing “The Wheels on the Bus” to the audience. During circle time, she often asked to sing the song. The class had done so earlier in the morning, and she carried it over into choice time. Tommy was still reserved during his play, so his puppets moved a bit to the song, and then he operated the curtain.

Figure 4. Scarlett and Tommy perform the first student-led puppet show.

Puppet Play Expands

After my initial observations of the children with the stage, I assumed that the children would want to perform a puppet show as a culminating activity, but that idea began to change as I observed how they used the puppets.

I had noticed that they enjoyed when the puppets “read” stories to them. During one observation, for example, Ms. Leti, an instructional assistant, read No David! aloud using the duck puppet. Six children eagerly sat on the classroom’s full-sized couch, leaning toward the book, while one sat on a stool and one on the floor.

Figure 5. The children are on the edge of their seats as the puppets read a story.

The child on the floor had rarely listened to read-alouds before, but he was almost in Ms. Leti’s lap, attending to the story as the puppet read. When one child would become loud or inattentive during the reading, he was hushed by another child (another unusual occurrence). When the story was complete, the children thanked the duck puppet and asked him to return the next day.

In addition to paying close attention when an adult used a puppet to read, the children had begun to create storylines that involved many puppets. I had noticed, however, that the number of audience members was dwindling. At the turning point, one child was sitting on Ms. Sue’s lap while four to five were packed behind the stage, moving the puppets and making them talk. The stage could comfortably accommodate two to three children, but many more wanted to be participants. The teachers had to work with the children on taking turns and being gentle with one another. The children wanted to stand while they operated their puppets, and four to five children smashed into one another in the process.

Figure 6. The children jockeyed for a spot behind the stage.

Ms. Sue and I demonstrated how to sit and extend the puppets above the stage, and this strategy helped ease the crowding. We also talked about taking turns and listening to friends—that is, spending some time as an audience member and some time moving the puppets. Taking turns proved difficult for the children. The children would take their turns operating the puppets and then leave the area until a space again became available behind the stage. The teachers did not impose a number of children that could play or a time limit. The children did so themselves.

Creating the Puppets

Inspiration for the New Direction

I made the decision to see whether the children might move in a different direction—away from creating puppet shows toward studying the different types of puppets and how they are made.

As I prepared for the activities to take a new direction, I remembered a puppetry workshop that I had attended at the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. The museum has an extensive educational section on its Web site, which includes a kindergarten through second-grade unit of study titled “Puppets: Here, There, and Everywhere” (http://www.childrensmuseum.org/teachers/unitsofstudy/puppets/activities.htm). As I read through the material and thought about the interests and abilities of my children, I focused on four types of puppets—finger, paper bag, stick, and shadow puppets. I felt that the finger puppet would be the simplest in construction and movement, and I decided to have the children work on finger puppets first.

Making Finger Puppets (February 20, 2008)

To begin our work with finger puppets, I printed pre-made, full-color Disney characters and laminated them for use at the puppet stage. I chose Disney characters because I felt that they would be recognizable to all of the children.

I made the same characters available in black and white for the children to color and use in making their own finger puppets. Although they found favorite characters, this attempt to engage them did not work as I expected. First, it was difficult to make the puppets small enough for the children’s fingers. Second, after the initial introduction, I noticed that the Disney puppets were strewn about the floor, and that some of the puppets were bent and torn. It seemed to me that the children felt no sense of ownership of these puppets, and they did not value playing with them.

After researching finger puppets, I came across the technique of creating a puppet around a 35-mm film canister. Polyfiber (e.g., small pieces of quilt batting) can be inserted and formed around a child’s finger, achieving a secure fit. Children can then decorate their film canisters. We made available pom-poms for heads, chenille stems for arms, and scraps of fabric for clothes. The children seemed to be delighted about selecting these items to construct their puppets. While making the puppets and when standing at the stage, they talked about the attributes of their puppets—the colors of the clothing, glittery hair, and so forth.

Figure 7. Tommy’s film canister puppet is almost complete.

In contrast to their treatment of the Disney-cutout finger puppets, the children walked around with the film canister puppets on their fingers and took them to the stage. When they were finished, they placed the puppets on the shelves behind the stage or gave them to the adults for storage.

Making Paper Bag Puppets (February 25, 2008)

Several days later, it was evident that the children’s interest in puppets was continuing, so I introduced paper bag puppets. I was eager to try this type, because the flap of the bags would let the children attempt more puppet manipulation and “conversation” than was possible with the finger puppets.

At circle time, the children and teachers talked about differences between the two styles of puppets: a film canister puppet was operated by moving a finger; a paper bag puppet by opening and closing the hand with the puppet on it. The children seemed excited and inspired by the conversation. They moved to the puppet-making center, where they found brown paper bags, yarn and lace, beads, and other art supplies awaiting them, set out by the adults. As with the film canister puppets, the children were given the freedom to create their own representations. The class had worked on portraits during the school year, and I noted that many of the children were putting recognizable facial features on their puppets.

Capitalizing on learning to use the bag flap, the teachers helped the children work on some conversation at the puppet stage, primarily adult to child. The focus of these interactions was on asking and answering simple questions, such as name and favorite activity.

Figure 8. Aimee works on her paper bag puppet.

Figure 9. Nate and a friend take their paper bag puppets to the stage.

Making Stick Puppets (February 27, 2008)

I decided that the next type of puppet-making experience would involve stick puppets. These puppets seemed to be a natural extension of the paper bag puppets; the bag puppets allowed children to re-create facial features, and the stick puppets allowed them to re-create clothing in addition to facial features. They had experience with animal puppets when they used the store-bought puppets. I wanted the boys and girls to experience human-like puppets as well.

The adults provided them each with a craft stick, a human body outline, and a selection of art materials. The children transformed the outline into representations of themselves. It was interesting to see how intently the children worked to match the puppets’ clothing colors and designs to their own.

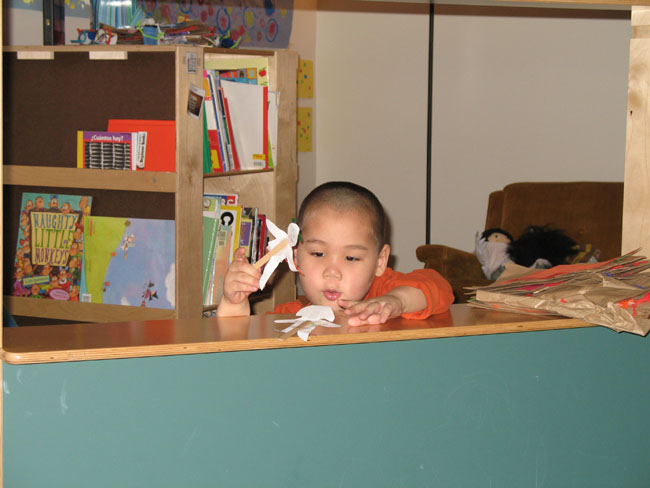

Figure 10. Nate’s favorite puppet was the body outline stick puppet.

The first activity with the completed stick puppets was singing the action song “Going on a Bear Hunt.” The song was extremely popular in the classes, and the children were able to make the movements and recite the lines. I sang the first line and my puppet acted out the movement, and the children repeated the words and the actions.

On the second day of working with the stick puppets, something occurred that amazed the teachers. To introduce a new texture to the project, I placed an overhead projector at the front of the room. Michael, a 5-year-old boy with Down Syndrome and a moderate mental handicap, began the year in the morning class and transferred to the afternoon. While in the morning class, Michael participated in a project on shadow and light. In fact, Michael had initiated that project with his interest in making hand shadows during recess. Several times during the shadow and light project, he had explored ways to create shadows using the overhead projector in the classroom.

On the second day of working with the stick puppets, Michael again found a leadership role. He turned on the overhead projector and began making full-body shadows. After he and his classmates delighted in this play, Michael used his hands to make shadows, just as he had done on the playground and in the morning class. Michael’s experience and the collaboration of his friends deepened the work with stick puppets and led us to the use of shadow puppets. The following is a conversation between several of the boys during shadow puppet play:

Nate: It’s Joey! No, it Rick!

Brennan: Mine is Joey!

Michael: Look, I fly (using his hands to make a butterfly).

Nate: Ricky jumps!

Ruben: Puppet’s name is Ruben.

Nate: There’s four people. They’re gonna play.

Ruben: Why you here? My puppet fell down. Help me! He fell off a rock! He have rope. He climb rope.

Robbie (age 3): My puppet want to jump.

Nate: The brother said be careful. Jump! Jump! Jump!

Robbie: My puppet. He want to go. Come on, Nate! He need to go!

Nate to Michael: Do you want to play with the mommy?

Michael: Yeah! Hi! Hi! Look!

All boys laugh.

Shadow Puppets (March 3, 2008)

Building upon the popularity of the stick puppets, I provided materials so that the children could create shadow puppets starting with simple outlines of objects. I set out craft sticks, tagboard, and colored cellophane. The children were given the materials and told that they could make any type of puppet they wished. Several girls in the morning class liked princesses and castles, so they worked with an instructional assistant to draw and cut out castles. They used the colored cellophane in the castle windows. The class had sung “The Wheels on the Bus” earlier in the day, and the boys in the afternoon had previously completed a project on automobile repair. They were eager to make bus puppets, and again, the cellophane was primarily used for windows. Their prior experience with the overhead projector and stick puppets seemed to lead naturally into exploring shadow puppets.

In the morning class, the children created a variety of shadow puppets, including castles, horses, and buses. In the afternoon class, most of the puppets the children made were buses.

Figure 11. Kyle experiments with his bus shadow puppet at the overhead projector.

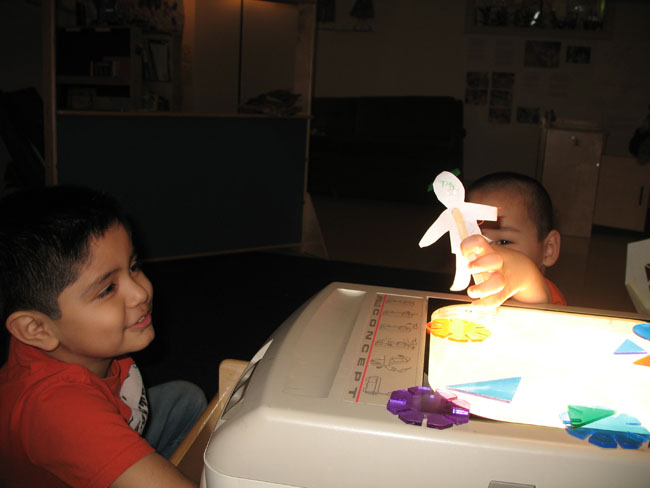

Figure 12. Ruben and Nate laugh as their puppets “climb ropes” and “fall off the rock.”

Nate found that the size of the shadow changed as he moved closer to and further away from the overhead projector:

Nate (moving the puppet): My bus is getting bigger! People on the bus go up and down.

Brennan’s stick puppet had a bent leg, and the children turned their buses into ambulances. Brennan and Kyle had this exchange:

Brennan: I need an ambulance.

Kyle (age 3): I help you. I a doctor.

Guest Expert Visit (March 5, 2008)

Ms. Nancy, the Warren Early Childhood Center’s coordinator of child care and a member of a puppet ministry, was able to lend her expertise to the project. On March 5, Ms. Nancy spent 30 minutes with each class showcasing different puppet styles, talking about puppet movement, and giving the children hands-on experience. She showed them how a puppet walks up to the stage and how a puppet can move its arms using a human arm glove.

Figure 13. Ms. Nancy, a guest expert, shows Gareth how to make the bird talk by moving his hand.

Although the children enjoyed all of her puppets, a few styles made an impact on the group. One stick puppet was simply a foam core head with a hair scrunchy mouth. A piece of fishing line was tied to the scrunchy, and when pulled, it appeared as if the puppet was talking. Three girls elected to make the “scrunchy mouth” puppet during choice time.

The children immediately connected the Muppet-type puppet to Ernie from Sesame Street.

Scarlett: Him’s Ernie!

Ms. Nancy: No, he’s not Ernie.

Maya (age 5): He’s Ernie’s friend. He looks like Ernie.

Figure 14. Beth interacts with the Kermit the Frog puppet during Ms. Nancy’s visit.

The final puppet was a long monkey whose arms and legs wrapped around the puppeteer. The monkey had been used in many shows and was beginning to show wear-and-tear:

Gareth (age 3): He doesn’t have eye.

Nate: He blinking.

Ms. Nancy did not have a marionette to show the groups, but she described the marionette style of puppet. So, the next day I read the Disney version of Pinocchio to the classes. The children were not familiar with the tale and expressed amazement that the story involved a puppet that could really talk and become a real boy. (The teachers had already talked with the children about differences between “true” stories and “made up” stories. Each time the adults would read a story aloud, the children would discuss the type of story and what made it fiction or nonfiction. It seemed to me that the children were aware that the story of Pinocchio was “made up.”)

Nate’s Story Extension

The story of Pinocchio influenced Nate in a way that surprised the adults. At choice time the next day, I found Nate behind the puppet stage with tools and the store-bought hand puppets:

Nate: I’m fixing puppets so they can talk. Then they will be real. They have to write their names all by themselves. This one (duck) will have lips. I will hang him up so he can dry. He doesn’t have teeth, because he doesn’t bite.

Figure 15. Nate fixes the lion puppet so “it can talk” following the Pinocchio reading.

Culminating Activity: A Puppetry Workshop

The culminating activity was always in the back of my mind throughout the children’s study of puppets. Adzooks (http://www.adzooks.com/index.html) had facilitated a puppetry workshop I attended at the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. Robin Lee Holm and David Wright, the Adzooks puppeteers, present 250 shows and workshops to 20,000 participants annually throughout Indiana and nationwide. Adzooks workshops were made available to schools through Young Audiences of Indiana (http://www.yaindy.org/), an organization that connects professional teaching artists and children in schools or other locations that serve them.

With the assistance of Young Audiences of Indiana, Adzooks puppeteers came to the Warren Early Childhood Center for a 2-hour workshop with my classes, which combined for the experience. The workshop was paid for by the school.

In a workshop titled “Anything Can Be a Puppet,” Adzooks puppeteers helped each child in my class create and animate a found object puppet—a puppet made from a spoon, a spatula, a toy rake, and a variety of materials that can be found around the home.

Adzooks puppeteers began by showing the children how a finger and a hand could be a puppet. Robin showed how, with a few embellishments, her hand could become a spider. Tommy, Michael, and Maya assisted in the enactment of “The Itsy Bitsy Spider.”

Figure 16. Three children perform Itsy Bitsy Spider with the Adzooks puppeteers.

Robin and David then showed the children objects from the classroom, such as keys from the dramatic play area, a block, and a book. They animated the objects as the children guessed what action the puppet was performing. This activity transitioned into the use of a spoon and shovel, and Robin made “Grammy” in front of the children with a spoon, foam shapes, chenille stems, and fabric:

All: "What's your name?"

Robin: "Grammy."

All: "Hi, Grammy."

Kyle: "Wow!"

There was a buzz in the room as the children moved to three tables with their spoons, shovels, and spatulas. The tables were stocked with found materials, and the children were free to create their puppets as they wished:

Ruben: "Here are my eyes."

Brennan: "My eyes are green."

Nate: "This is a smile."

Maya: "My mom wears earrings. She always wears earrings. I can make earrings and eyelashes, too."

Nate: "This heart is my eye."

Maya: "This gives me an idea."

Brennan: "Hair, I need hair."

Figure 17. Lola selects the material for her puppet’s hair.

After the children created their puppets, they moved to the costume table.

Gareth (age 3): “My friend is a lion. Roar!”

As they completed the puppets’ costumes, the children freely moved around the classroom with the puppets, and many of them found their way to the stage.

Figure 18. Tommy, Maya, and Gareth try out their found object puppets at the stage.

Adzooks puppeteers soon brought the group together, and the children introduced their puppets one at a time, asking and answering the two questions—“What is your name?” and “What do you like to do?”

I felt that the workshop was successful because the children were actively engaged throughout the afternoon. The boys and girls were intent on creating their puppets, and all children were able to participate regardless of their communication skills.

I didn’t realize the full impact of the workshop, however, until a few days later when I spoke with the parents of Will (age 3) and Tommy. Will’s mother said that he continued to play with his found object puppet, and Tommy’s parents said that every spoon in their home was now a puppet, because Tommy and his sister thought it was “so neat.”

Teacher Reflections

The children’s investigation of puppets did not develop in the manner in which I expected, but that is what made it seem such a rewarding and successful experience. The children worked with me on two topic webs—one very early on and the other following the expert visit. My experience with the children led me to believe that if I came up with subtopics, the children would contribute their ideas, and that is how the web could be constructed. The subtopics were the same for both webs—What Puppets Are Made Of, How Puppets Move, Feelings about Puppets, and Types of Puppets. Comparing the webs enabled me to see how much the children learned about puppets. In the first web, little of the information had been listed by the children. They did not know what materials might be used to make puppets. Only one child had an idea of how puppets moved (she said they moved when her hand moved). The only feeling listed by the children was “fun,” and the only type of puppet named was “paper bag puppet.”

Following the expert visit, the web was richer, with contributions from many of the children. For What Puppets Are Made Of, the boys and girls listed fabric, pom-poms, bag, craft sticks, and other items that they had used themselves. In responding to How Puppets Move, children still noted that puppets moved when the puppeteer’s hand moved, but they also mentioned puppet body parts that could move, and they used the words “fast,” “slow,” and “run.” Their list of feelings expanded to “happy,” “funny,” “silly,” and “make me laugh.” In the Types of Puppets category, the children named all of the kinds of puppets that they had created in the classroom up to that point, as well as those brought in by the guest expert.

It was easy for me to underestimate the importance of a craft stick until I saw it turned into a puppet and witnessed the children engaged in self-initiated dialogue and play. An overhead projector was merely a source of light, until a student with Down Syndrome and a moderate mental handicap created shadows and became a classroom leader. Experiences like this are about more than building to a culminating event. They are about making observations and listening to the children, and they are about letting go as a classroom teacher and allowing the interests and skills of the smallest learner to be the guide.

Figure 19. Children show puppets to the audience.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the children in my classes for their enthusiasm and imagination. They inspire and amaze me each day, and I am so proud to be their teacher and have the opportunity to learn with them. To Ron Smith, director of the Warren Early Childhood Center, thank you for bringing me to the center and giving me the chance to grow. To Sue McGovern, Leti Velasquez, and Lisa Wildrick, my instructional assistants, thank you for your daily contributions to the children. To Adzooks, Young Audiences, and the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis, thank you for providing such rich experiences for all children. Project documentation shared with the permission of the MSD Warren Township.

Author Information

Kelli Servizzi is a developmental preschool teacher at the Warren Early Childhood Center in Indianapolis, Indiana. She received her master’s degree in special education from Butler University.

Kelli Servizzi

Warren Early Childhood Center

1401 N. Mitthoefer

Indianapolis, IN 46229

Email: kservizz@warren.k12.in.us

Appendix

English/Language Arts |

|

| F.1.7 | Tell something that a favorite character does in a story. |

| F.1.14 | Watch and listen to a story to completion or for ten or more minutes. |

| F.1.37 | Ask and answer simple questions about a story being read. |

| F.1.38 | Ask adult to read printed information. |

| F.1.42 | Pretend to do something or be someone. |

| F.1.43 | Use new vocabulary learned from experiences. |

| F.1.44 | Act out familiar, scripted events and routines. |

| F.2.2 | Request or select a story by the title of the book. |

| F.2.3 | Tell simple stories from pictures and books. |

| F.2.4 | Express what might happen after the action in a picture. |

| F.2.5 | Tell one thing that happens in a familiar story. |

| F.3.2 | Actively look for or keep attending to things that an adult points to, shows, or talks about. |

| F.3.13 | Talk about the cover and illustrations prior to the story being read. |

| F.4.1 | Draw pictures and scribble to generate and express ideas. |

| F.4.6 | Position paper for writing. |

| F.4.7 | Write from left to right. |

| F.4.8 | Write using pictures, letters, and words. |

| F.4.9 | Use writing or symbols to share an idea with someone. |

| F.5.4 | Draw name or a message on a card or picture. |

| F.5.5 | Give writing to someone as a means of communication. |

| F.7.17 | Initiate turn taking in play. |

| F.7.20 | Repeat simple sentences as presented. |

| F.7.21 | Engage in reciprocal conversations for two to three exchanges |

| F.7.30 | Pick from two ideas to talk about. |

Mathematics |

|

| F.1.21 | Pass out objects or food to people or characters. |

| F.3.13 | Categorize familiar objects by function and class. |

| F.6.8 | Identify similarities and differences in objects. |

| F.6.18 | Imitate the use of an adult tool in play. |

| F.6.19 | See a simple task through to completion. |

Science |

|

| F.1.2 | Interact with and explore a variety of objects, books, and materials. |

| F.3.1 | Participate in activities using materials with a variety of properties (e.g., color, shape, size, name, type of material). |

Social Studies |

|

| F.1.2 | Relate new experiences to past experiences. |

| F.3.28 | Pretend to take care of a doll by feeding and other activities. |

| F.3.29 | Play the role of different family members through dramatic play. |

| F.3.36 | Help clean up after doing an activity. |

| F.5.9 | Use interpersonal skills of sharing and taking turns in interactions with others. |

Music |

|

| F.1.2 | Verbally express enjoyment. |

| F.1.3 | Sing along to familiar songs. |

Visual Arts |

|

| F.2.1 | Participate freely in dramatic play activities that become more extended and complex. |

| F.2.2 | Express self in dramatic play through story telling, puppetry, and other language development activities. |

| F.2.3 | Compare and contrast own creations and those of others. |

| F.2.7 | Show individuality by actions such as drawing a pumpkin that differs in color and design from the traditional. |

| F.2.8 | Engage in cooperative pretend play with another. |

| F.2.10 | Use objects as symbols for other things (e.g., a scarf to represent bird wings or a box to represent a car). |

| F.2.11 | Pretend through role-playing. |

| F.2.14 | Watch an activity before entering into it. |

| F.2.15 | Enjoy repetition of materials and activities to further explore, manipulate, and exercise the imagination. |

| F.2.19 | Use a variety of materials (e.g., crayons, paint, clay, markers) to create original work. |