Volume 15 Number 2

©The Author(s) 2013 Collaboration and Subsidized Early Care and Education Programs in Illinois

Abstract

As a result of policy changes following welfare reform in 1996 and the costs associated with providing high-quality early care and education for children of low-income working families, agency collaboration in the state of Illinois has become an increasingly salient feature of subsidized early care and education programs (SECE). The authors examine how the three major subsidized early care and education programs in Illinois collaborate to meet the diverse needs of low-income children and families. Based on an in-depth literature review and semistructured interviews with state and local stakeholders, the authors find that collaboration in the SECE system is frequent, despite different program eligibility criteria, guidelines, performance expectations, perspectives on quality measures, and mechanisms for monitoring. However, the extent to which collaboration occurs is not well understood, which may affect how stakeholders interpret the impact of publicly funded early care and education programs. This may prevent accurate characterization of children’s early care and education experiences and hinder assessments of how such experiences impact their development.

Introduction

In Illinois, a salient feature of the subsidized early care and education system (SECE) is collaboration among agencies that provide Head Start, the current state-funded prekindergarten program (Preschool for All), and child care subsidies. The extent to which SECE agency collaboration occurs and its effect on program and child outcomes, however, are not well understood. Increased collaboration across agencies in the last 15 years has led to the use of multiple funding streams at the provider level, resulting in a more complex and varied landscape of SECE services than is currently acknowledged by researchers, practitioners, and policy makers.

This paper presents findings from an exploratory study of how agencies and providers collaborate to provide SECE services in Illinois and the key policies that led to these forms of collaboration. It draws on an in-depth literature review and semistructured interviews with 16 stakeholders conducted in early 2013.

Defining Collaboration

This study approaches SECE system collaboration from the perspectives of three groups of actors: agencies, providers, and families. Bound by policy, agencies define the regulations and standards that govern the allocation of funding for SECE programs. Providers use these programmatic funding streams to provide services and implement the policies set by agencies. Eligible low-income families choose providers to fulfill their need to work, as mandated by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996, and to provide quality care for their children. The interaction across agencies, providers, and families defines the patterns of collaboration within the SECE system.

Our definition of agency collaboration is consistent with that disseminated by the Illinois Early Childhood Collaboration: a “process by which agencies formally commit themselves on a long-term basis to work together to accomplish a common mission” (Illinois Early Childhood Collaboration, n.d.). Agency collaboration is expressed in the rules and enforcement mechanisms that govern interaction among agencies. Most collaborations across SECE agencies result from hybrid forms of formal and informal agreements along with formal and informal enforcement mechanisms. This collection of agreements ultimately defines what types of funding providers can use and the set of SECE standards to which they are subject. By combining diverse public funding streams to supply SECE services that meet the needs of working families, providers are thus regulated by multiple agencies with different standards.

Collaboration across agencies is carried out through design and implementation of coordinated strategies to facilitate provision of early care and education services, often through the braiding and/or blending of funding across SECE providers. Frequently, collaboration across agencies is pursued for the purpose of providing full-day SECE services to low-income families. This form of collaboration allows providers to bear their operational costs in exchange for meeting common quality standards of practice. Collaboration requires mechanisms to facilitate the use of multiple funding streams by a single provider, such as standardization of quality rating systems, professional development practices, sharing of resources and staff, and joint administration of programs.

Key Policies Shaping Today’s SECE System

Dynamic processes resulting from policy change have shaped the SECE system in Illinois today. In this section, we discuss the evolution of policies associated with discrete SECE programs—Head Start, Preschool for All, and the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF)—that are key to understanding agency collaboration in the current SECE system in Illinois.

Welfare Reform and CCDF

Collaboration rose markedly on the agendas of SECE agencies following the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996, also known as welfare reform. When the legislation was enacted, an array of early childhood programs and services existed across Illinois. Head Start programs operated in school- and community-based centers. State-subsidized prekindergarten and comprehensive child development centers (Chicago Parent Child Centers) similarly offered early education programming in school settings. The existing SECE programs had the primary objectives of fostering child development and school readiness.

Welfare reform substantially increased the substantially increased the funding available to providers to implement SECE services with the creation of the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG),1 which consolidated all previously established child care subsidy programs and created a new means-tested program. With federal guidelines requiring parental employment, job training, or school enrollment as a condition of eligibility, CCDBG signaled a new policy orientation that focused on promoting family self-sufficiency (Blau, 2003).2 The newly restructured child care system diversified the state’s landscape of SECE programs, creating another funding stream from which these providers and families could draw to cover the cost of full-day, full-year care.

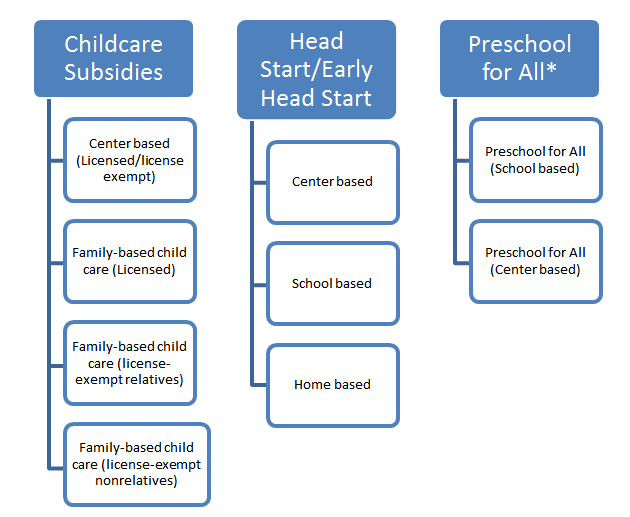

Under CCDBG, states were given a wide degree of discretion to design their child care subsidies programs.3 The Illinois Department of Human Services (IDHS) was designated as the central agency in administering the new Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP), funded by the CCDF block grant, state matching funds, and some money from other programs, including Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). In Illinois, CCAP prioritized parental choice, offering families vouchers to subsidize a wide variety of providers ranging from relatives providing care at home to licensed center-based care (see Figure 1). CCAP has also issued grants to delegate agencies, such as the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS).

Figure 1. Illinois SECE programs and settings.

*Preschool for All is funded by the Early Childhood Block Grant (ECBG), which also funds the Prevention Initiative (PI). PI programs are not part of this analysis.

Notably, Illinois made a strong commitment to supporting Family Friend and Neighbor (FFN) Care, especially in Chicago. CCAP subsidizes informal FFN care as well as licensed and license-exempt family-based child care; its flexibility allows low-income families to simultaneously use multiple combinations of subsidized care. For example, families can receive a voucher for care by a FFN provider along with multiple forms of center-based child care programs (Head Start, Preschool for All, community-based child care, or combinations of them). The availability of subsidies for FFN providers potentially increases low-income families’ access to wrap-around care hours for their children. Adding more subsidies for low-income families also increased the number of SECE providers. This flexibility, coupled with the fact that CCAP was funded with federal and state money, ultimately redefined the landscape of SECE services available to low-income Illinois children. While consistent with the CCDF objectives of promoting parental employment, the policies that led to increasing availability of and enrollment in multiple programs did not articulate a strategy for assuring that children receive high-quality care.

In Illinois and across the nation, the policy goal of sustaining parents’ work efforts through child care subsidies diverged from the historical goals of Head Start and state prekindergarten programs to foster school readiness and child development. Sharing the target population of low-income children, state agencies with stakes in early childhood recognized that collaboration offered opportunities to address the dual goals of providing educational, enriching experiences for children and supporting parental employment.

Head Start Reauthorizations

The structure for funding the Head Start program has changed relatively little since the program’s inception in 1965. However, the programmatic rules, regulations, and conditions for funding have changed dramatically since welfare reform in 1996 (see Appendix A for funding and enrollment changes). Head Start amendments introduced in 1998 launched conceptual, cultural, and structural changes to the program, including requirements about quality improvement, school readiness, and staff and teacher certification (Gish, 2008). The 1998 reauthorization also explicitly promoted collaboration between SECE agencies with new mandates that required Head Start State Collaboration Offices (HSSCO) receive expansion grants to coordinate with state child care offices and resource and referral agencies (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1999). The 1998 amendments also prioritized funding of Head Start providers that coordinated with other funding sources to increase the number of hours that children could receive early education and care (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1999). Observers also noted that reauthorization implicitly discouraged providers from seeking funding for full-day programming, with the understanding that full-day care could be provided in collaboration with the newly created child care subsidy program (Head Start Bureau, 2001).

Collaboration has been a focal point of Head Start since 1998. The reauthorization of Head Start in 2007, consistent with the increased accountability created by the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, introduced more stringent expectations for student outcomes, program accountability, and learning standards. The 2007 reauthorization also highlighted collaboration between Head Start and state and local SECE agencies as the central mechanism for increasing access to and the quality of Head Start programs. The 2007 amendments called for grantees to receive collaboration grants to help Head Start agencies collaborate in planning, administering CCDBG, and aligning programmatic content and standards with their state's early learning standards (Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007). The reform also encouraged collaboration to provide “full working-day, full calendar year” Head Start programs (Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007).

State-funded Prekindergarten

State-funded prekindergarten programs in Illinois date back to 1985 when the State Board of Education (ISBE) secured state funding to administer block grants targeted to early childhood education programs for at-risk children (Illinois State Board of Education, 2004). In 1997, new legislation created the Early Childhood Block Grant (ECBG), substantially increasing funding to expand the state-funded prekindergarten program. The ECBG included new funds earmarked for birth-to-3 programming to be coupled with existing state preschool funds for the creation of a birth-to-5 funding stream to be managed by state school districts (Ounce of Prevention Fund, 2009). By FY 2003, Early Childhood Block Grants subsidized preschool experiences for about 56,000 children in 642 school districts through three programs: 1) Prekindergarten At-Risk program, 2) the Parental Training program, and 3) the Prevention Initiative program (Illinois State Board of Education, 2004).

The Prekindergarten At-Risk program became the Preschool for All program (PFA) in 2006, when the state created the first voluntary universal preschool for 3- and 4-year-old children (Ounce of Prevention, 2009). While designed to be a universal program, because of limited funding, PFA currently prioritizes children who are most at-risk. Limited funding also prohibits PFA from subsidizing full-day care that, in many cases, is required by low-income working parents.

Given its limited resources, the PFA program considers collaboration with Head Start a primary strategy to meet the physical, mental, social, and emotional needs of young children (Illinois Early Learning Council, 2006). Program administrators have also sought to improve integration with CCAP by facilitating children’s transitions across settings by supplementing funding and resources to providers already using CCAP. Developing a consistent set of quality standards common to all SECE providers is also a programmatic priority of the PFA program.

State subsidized preschool in Illinois has been a strategy for increasing school readiness among children at the highest risk of academic failure. Lack of school readiness, the state has long recognized, imposes high costs for the entire school system that can be reduced by high-quality preschool experiences. Collaboration with other programs (primarily CCAP and Head Start) allows ISBE to achieve its school readiness goal, especially in areas where school districts have limited physical infrastructure. Collaboration of PFA with other programs also was driven by the need to share costs of serving hard-to-reach children.

Methods

Sample

Because this was an initial inquiry, we intentionally selected a sample of senior administrators and policymakers at both the state and city levels who are responsible for program implementation or coordinating and oversight of the SECE system. Our sample included representatives from a number of city agencies, including but not limited to the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) and the Chicago Department of Family and Social Services (DFSS), as well as a number of state agencies and advocacy organizations, including Illinois Action for Children, the Ounce of Prevention Fund, the Illinois DHS child care division, the Head Start state collaboration office, and the Governor’s Office of Early Childhood Development. About half of the sample (16 participants) represented Chicago and the other half represented the other regions across the state.

Data Sources

We developed a semistructured, flexible interview guide that allowed informants to respond according to their roles, responsibilities, and knowledge (see Appendix B). The interview guide was developed to identify key issues that state and local program administrators and policymakers encounter in implementing SECE programs; particular attention is given to collaboration, funding, program quality, and assessment and monitoring.

Although all 16 informants had knowledge of both the state and city systems, some were more knowledgeable about the system at the state level and others knew more about Chicago. Twelve informants were interviewed in person and four by telephone. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. Respondents were informed that their comments would be confidential and that no individuals would be identified in written reports. Interview data were augmented by additional documents provided by informants after the interviews.

Analysis

Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Interview data was coded into major categories and themes using both deductive and inductive qualitative methods. Coding was guided by the interview protocol, but we also were open to new topics and themes that emerged in the conversation.

Findings

Evolution of Collaboration in Illinois

Illinois, according to our informants, has a long history of collaboration in the provision of early childhood care and education. Bureaucrats from ISBE and IDHS, for example, met regularly in the early 1980s to discuss needed policy changes and strategies for state-level collaboration around state subsidized preschool (Bushouse, 2009). Illinois leadership has regarded collaboration across CCAP, Head Start, and state-funded prekindergarten programs as a way to give children a more enriched educational experience than child care alone.

The policy changes motivated by welfare reform both encouraged and complicated collaboration among SECE providers, according to our informants. The sweeping changes introduced by the 1996 welfare reform led historically siloed SECE agencies to become more unified in their strategies. Head Start, child care subsidies, and state prekindergarten programs, for example, increasingly focused on full-day programming to meet the needs of working families. Currently, Illinois providers take advantage of various incentives that allow them to combine Head Start, PFA, and CCAP funding.

Policies that allow providers to combine funding from different SECE agencies to offer full-day, full-year early care and education services have had the most salient impact on collaboration across the state. The increasing use of multiple funding streams following welfare reform allows providers to offer full-day services and and enables families to participate in multiple programs. One state administrator remarked, “Collaboration was the obvious remedy, teaming up [between Head Start], PreK and/or child care … [as] families were [going] back to work.” Across sectors, informants from local agencies agreed that, in the words of Selden, Sowa & Sandfort (2006), “coming together to link discrete services and resources into multifaceted delivery systems that, in theory, decreased fragmentation and redundancy and increased access” and allowed providers to coordinate “actual service delivery” (p. 412).

Our respondents indicated that in addition to the 1996 welfare reform, state-level policy changes have affected the way SECE agencies collaborate in Illinois over the past decade. State legislation in 2003 created a formal collaborative governance structure with the passage of the Illinois Early Learning Council Act (Illinois General Assembly, 2003). Intended to serve in an advisory capacity to coordinate and guide a comprehensive early learning system through a politically appointed public-private partnership, the Early Learning Council (ELC) soon took the lead in statewide efforts to achieve a comprehensive early learning system. Although the primary objective of the ELC quickly focused on passing universal preschool legislation, the group also assumed many functions to coordinate collaboration initiatives.4

Another important change with implications for how agencies collaborate in supplying SECE programs in Illinois occurred in 2008, when the state established a P-20 Council, which was authorized “to foster collaboration among state agencies, education institutions, [and] local schools … to collectively identify needed reforms to develop a seamless and sustainable statewide system of quality education and support” (Illinois P-20 Council, n.d.). In 2009, the governor created the Office of Early Childhood Development (OECD) to provide support and leadership for an integrated system of early childhood services.

In addition to existing state and federal policy, recent prospects for federal funding have also increased collaboration among state administrators, our informants noted. The Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge (RTT-ELC) application process, for example, created an opportunity for state agencies involved in the supply of SECE programs to increase their system integration and align quality indicators. Illinois’ RTT-ELC plan includes a new Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS) designed to bring all three SECE programs under the same quality rating umbrella.

Collaboration in Practice

Collaboration has created a SECE system in Illinois that is heterogeneous and complex. Our informants’ comments demonstrate how collaboration policies have been implemented and paint a picture of collaboration that looks very different from agency to agency. The 1996 welfare reform, administrators confirmed, was a turning point; agencies now look to “collaboration [as] the obvious remedy” to support the teaming of SECE agencies and providers to fund full-day services. Families with different needs, values, and preferences often use multiple providers to “wrap around” care for their children, allowing them to sustain their work efforts while exercising choice when attempting to provide quality of care for their children. Agency collaboration, providers’ use of multiple funding streams, and family use of multiple providers have led some observers to characterize the early childhood system as a “patchwork” of discrete, not well-coordinated programs (Murdock, Cline, & Zey, 2012; Raden & McCabe, 2004).

Since 1996, one informant said, “almost anything you can think of [in terms of collaboration] is either going on now or has gone on.” Indeed, according to an Illinois Department of Human Services report (2007) on the state’s child care collaboration program, Illinois SECE providers are using every conceivable legal and allowable model for collaboration. The Illinois Child Care Collaboration Program, led by the state Head Start State Collaboration Office (HSSCO), supports several partnership models for centers or homes, including (1) child care collaboration with Early Head Start or Head Start, (2) child care collaboration with PFA, (3) child care collaboration with Birth to Three programs funded by the state’s ECBG, (4) Head Start collaboration with PFA, and (5) a collaboration among child care, Head Start, and PFA. Within each model, there are further variations in implementation. For example, one provider can blend or braid funds from multiple sources at a single location, or two or more providers may partner to serve children at a single site. In addition, providers may just share space or they may share funding and programming, and costs of collaboration may be handled in a variety of ways (e.g., subcontracts, purchase of services, or other interagency agreements).

Most collaborations in the state involve shared funding—either a blending or, more frequently, braiding in which funds from one stream are designated for particular purposes (e.g., a certified teacher) while funds from another stream are allocated to other purposes (e.g., rent or a family support specialist). One informant described the heterogeneity of collaboration in Illinois:

We’ve had collaborations where the Head Start entity would pay a stipend to the child care partner, and then Head Start provides the family support services and case management. [We’ve also had] shared classroom space, shared teaching, [where] there was actually no big money exchanged. And then there [are other] collaboration models, in which one agency gets all the funding itself and streams are blended.

Although some informants provided examples in which teachers or curricula are shared, these examples were infrequently mentioned, which suggests that such collaboration is rare.

The complexity of the SECE system is most evident in the myriad ways that providers and agencies combine funds from multiple programs to make “wrap-around” care possible. Collaboration, our informants emphasized, augments what a Head Start or PFA program can provide by making it possible for working families to have full-day child care and meet employment requirements of the 1996 welfare reform. Our informants noted that some collaboration models are better than others in accommodating the dual objectives of providing high-quality child care and supporting parental employment efforts.

Several informants stressed that unlike many other states, Illinois permits homes or family child care (FCC) to partner with Head Start or PFA programs:

Even in the homes, you can do collaboration. The provider will designate what time of day is for what program, so that there is some program oversight that’s directly tied to the funding stream. ... Same thing [with Early Head Start]; it’s a collaborative model … because the federal dollars we get for Early [Head Start] are very low.

Collaboration with child care providers has created challenges for practitioners and early childhood administrators. For example, in a model supported by the Community Connections program, children are transported from FCC to a part-day center-based PFA program four days a week, and the fifth day, the teaching staff visit the providers to share curriculum materials and ideas (Illinois Action for Children, 2008). The intent of that fifth day is to extend the developmental component of PFA into the FCC hours. This model’s ability to meet children’s developmental needs, however, depends on the overall level of quality of the FCC providers as well as the number and smoothness of transitions between the home and center (Illinois Action for Children, 2008). Indeed, as noted below, the HSSCO prefers collaborations that involve minimal transitions from one setting to another. As an agency administrator commented, “The child care homes are a different issue altogether. It’s going to take a lot of work to have some deep understanding of [their quality].”

Our informants also reported that the models and types of collaboration in different communities or neighborhoods may vary, depending on family characteristics and needs. In communities where a large percentage of mothers do not work, and consequently do not qualify for child care subsidies, collaboration may look different than in areas with a large percentage of working parents. In one largely immigrant community, this was observed by one of our informants.

We want to get these kids—English-language learning kids, monolingual families at home, Spanish-speaking—into a preschool experience here. A Head Start Preschool [for All] collaboration would have a Head Start experience in the morning and a preschool teacher in the afternoon. Parents love this because they get about a six-hour school day for their preschool-age children. … We’re doing it is because the funding is making us. It highlights the fact that there’s a variety of different ways to do these collaborations, and we’re trying to be creative.

Interviews also revealed some misconceptions of statewide collaboration that are not currently reflected in research. Collaboration across agencies, for example, offers a greater variety of nonparental care experiences for children than is typically acknowledged in implementation and outcomes evaluations. Although the HSSCO tracks which communities engage in collaboration programs it has approved, no information is available on the frequency of different model combinations. Several participants acknowledged that a range of formal and informal collaborations exist, but most are not formally tracked. One informant commented:

When [HSSCO] sets up models for collaboration, [there isn’t just] one model. We’ve given lots of best practice, lots of examples, lots of guidelines but [not] in terms of an actual this-is-how-you-should-do-it. Head Start [usually] wants to extend the day. … It’s hard to say what models we’re using because almost anything you can think of is either going on now or has gone on.

Several informants pointed to the lack of accurate data on the number of children who are served by more than one funding stream—both concurrently and over time—that could inform decisions on resource allocation, program planning, and system-building. State administrators acknowledged that assessment would benefit from data that captures the nature of children’s early experiences in multiple programs concurrently and over time. An agency administrator stated:

[Head Start has] a wide range of program options, plus they had for many years a wide range of what they called “the local design options,” [but] that’s part of the dilemma. So when [a researcher] does the wonderful needs assessment of children in the state and we see utilization data, service need and use data, it’s [meaningless]. The data is not able to capture how one slot helped three funding sources go for one child, or three kids, three different kids. So it looks at times like the state is completely flooded and other times like there’s huge need, and it’s very difficult to unpack it.

Another administrator noted the variety of collaborations around the state, the preference for those that provide continuity of care, and the lack of systematic data on their prevalence:

[HSSCO] only approves collaborations consider[ed] to be the highest quality partnerships, which is what is good for kids, which minimizes the transition. We know there’s a whole lot of collaborations that go on when children are moved to a different setting, but they are not part of what [are] approved collaborations. [We] know a lot about what goes on in collaborations with Head Start. We don’t know so much about the collaborations with PreK [PFA].

High management costs associated with blending and braiding strategies were also described by our informants. While a consensus existed among these administrators that the blending or braiding of funding streams is necessary to improve the quality of children’s experiences in early care and education programs, they recognized that the impact of such collaboration is not well understood. Establishing and enforcing common understandings of quality has remained elusive, and no data are available to confirm whether coordinated or blending funding actually increases quality or helps promote children’s development or readiness for kindergarten. One informant said, “Our instinct is that even if you blend all the funding streams together, it’s still not enough to really do what you would want to do in an ideal world, so we want some data to prove that.”

Conclusion and Implications

Policy changes at the state and federal levels have dramatically changed the supply of SECE programs in recent years in Illinois and increased the complexity of the SECE system in Illinois. Given the many combinations of SECE programs, the need for strategic analysis of interactions within the SECE system and their effect on the experiences of low-income children is crucial. Our informants confirmed that there are not sufficient data to analyze the relationships among the three most heavily funded SECE programs, namely CCDF, Head Start, and state prekindergarten programs. Because little is known about how funding streams are combined and how those combinations affect the provision of early care and education services, there is a risk of misclassification errors when identifying the types of SECE programs in which children are enrolled. This lack of data on collaborations across agencies has resulted in SECE programs that are not appropriately defined, organizational relationships that are poorly understood, and a SECE system that is often mischaracterized. We maintain that this lack of knowledge perpetuates a “black box” of actual practice that must be made more transparent so policies and practices can be designed that better address the needs of low-income children and their families.

Many of our informants commented on the “timeliness” of our inquiry, noting recent efforts to create and implement a new statewide QRIS and to develop a coordinated screening and assessment system for early care and education programs in Chicago. Their comments further reinforced awareness of the need for data on (1) the types of individual and collaborative programs children currently experience, (2) the costs of these programs (including costs of coordination activities), and (3) the ways these programs benefit families and impact child development. Given the potential new federal initiative for a universal preschool program,5 which could substantially increase funding for SECE programs across the country, better understanding is needed on how agencies and providers collaborate to deliver SECE services and how collaboration affects program quality, child development, and family employment.

Collaboration has been implemented for a variety of reasons. Leaders in early care and education have turned to collaboration to accommodate low-income families’ different needs, values, and preferences for child care and to address the fact that collaboration is needed to offer comprehensive, high-quality, wrap-around care. Our evidence suggests that collaboration in the SECE system happens often, despite differing program eligibility criteria, guidelines, performance expectations, perspectives on quality measures, and mechanisms for monitoring. Collaboration occurs even though agencies place relatively different weights on the dual objectives of sustaining parental employment and providing children with high-quality care.

This paper is offered in an effort to stimulate discussion about how children’s early care and education experiences are described and assessed. The pervasiveness of collaboration in Illinois demonstrates that it can be misleading to talk about a “Head Start” or “PreK” child or a typical “child care subsidy” experience without addressing the impact of collaboration. To understand the impacts of different programs on child development, we must first acknowledge, then understand, the diversity and complexity of the SECE system. As the extent to which full-day services for low-income children are supported by a combination of PFA, Head Start, and/or CCAP funds remains largely unknown, further investigation is necessary.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the participation of our informants who graciously made time to talk with us and often provided additional documents to facilitate understanding of their programs and the SECE system.

Notes

1 A description of the history and evolution of the CCDBG can be found in Blau (2003), Blau and Currie (2004), and U.S. House Committee of Ways and Means (2008).

2 Federal guidelines also allocated up to 4% of the CCDBG budget to improvements in quality of care.

3 Nationwide, the Administration for Children and Families coordinates CCDF through the Office of Child Care (OCC), which in turn delegates to the states the administration and management of child care subsidies funded by CCDF.

4 The ELC subcommittees are charged with examining how to remove barriers to and make recommendations for blended and braided funding to sustain quality early childhood development programs.

5 In his 2013 State of the Union address and FY2014 budget, President Obama proposed spending $77 billion to create a universal prekindergarten program—similar to PFA in Illinois—for all 4-year-olds through federal-state partnerships.

References

Blau, David M. (2003). Child care subsidy programs. In Robert A. Moffit (Ed.), Means-tested transfer programs in the United States (pp. 443–516). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Blau, David, & Currie, Janet. (2004, August). Preschool, day care, and afterschool care: Who’s minding the kids? (NBER Working Paper 10670). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bushouse, Brenda K. (2009). Universal preschool: Policy change, stability and the Pew Charitable Trust. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Gish, Melinda. (2008). Head Start: Background and issues (CRS Report No. RL30952). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Head Start Bureau. (2001, March). Financial management issues in Head Start programs utilizing other sources of funding (Report ACYF-IM-HS-01-06). Washington, DC: Author.

Head Start Bureau. (2012). Head Start program facts fiscal year 2012. Washington, DC: Author.

Illinois Action for Children. (2008). State-funded preschool and home-based child care: The community connections model. Chicago, IL: Author.

Illinois Department of Human Services. (2007, November). Child care collaboration program evaluation report. Springfield: Author.

Illinois Early Childhood Collaboration. (n.d.). What is early care & education collaboration? Springfield, IL: Author.

Illinois Early Learning Council. (2006, Spring). Preschool for All: High-quality early education for all of Illinois’ children.

Illinois General Assembly. (2003). Public act 93-0380. Springfield: Author.

Illinois P-20 Council. (n.d.). About us. Champaign, IL: Author.

Illinois State Board of Education. (2004, June). Illinois prekindergarten program for children at risk of academic failure: FY 2003 evaluation report.

Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007, Pub. L. No. 110-134, § 1(a), 121 Stat. 1363 (2007).

Murdock, Steve H.; Cline, Michael; & Zey, Mary. (2012, August). The children of the Southwest: Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics impacting the future of the Southwest and the United States. Washington, DC: First Focus.

Ounce of Prevention Fund. (2009, August 4). Governor Quinn partially restores preschool funding. Ounce of Prevention Fund.

Raden, Anthony, & McCabe, Lisa A. (2004). Researching universal prekindergarten: Thoughts on critical questions and research domains from policy makers, child advocates and researchers. New York: Foundation for Child Development.

Selden, Sally Coleman; Sowa, Jessica E; & Sandfort, Jodi. (2006). The impact of nonprofit collaboration in early child care and education on management and program outcomes. Public Administration Review, 66, 412–425. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00598.x

U.S. General Accounting Office. (1999, November). Education and care: Early childhood programs and services for low-income families (GAO/HEHS-00-11). Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. House Committee of Ways and Means. (2008) Background material and data on the programs within the jurisdiction of the Committee on Ways and Means (Child care chapter). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Author Information

Dr. Julie Spielberger is a research fellow at Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. Her research focuses on child development, kindergarten readiness, early childhood programs and system-building, and quality improvement initiatives.

Julie Spielberger, Ph.D., Research Fellow

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago

1313 East 60th Street

Chicago, IL 60637

Dr. Wladimir Zanoni is an economist and senior researcher at Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. His research interests include the effects of subsidized early childhood programs on social policy and child and parent outcomes.

Elizabeth Barisik, M.Ed., is a project associate at Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. Her research interests include early childhood policy and program development, child development, and school readiness.

Appendix A

| Year | Enrollment | Funding (in millions of dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 793,809 | 3,980.55 |

| 1998 | 822,316 | 4,347.43 |

| 1999 | 835,365 | 4,658.15 |

| 2000 | 857,664 | 5,267.00 |

| 2001 | 905,235 | 6,199.12 |

| 2002 | 912,345 | 6,536.60 |

| 2003 | 909,608 | 6,667.57 |

| 2004 | 905,851 | 6,774.85 |

| 2005 | 906,993 | 6,843.11 |

| 2006 | 909,201 | 6,872.06 |

| 2007 | 908,412 | 6,888.57 |

| 2008 | 906,992 | 6,877.98 |

| 2009 | 904,153 | 7,112.79 |

| 2010 | 904,118 | 7,112.78 |

| 2011 | 964,430 | 7,559.63 |

| 2012 | 956,497 | 7,968.54 |

| Source: Head Start Bureau (2012) | ||

Appendix B

Interview Protocol for Illinois SECE Collaboration Study

Background

- What is your position and title? How long have you held this position? What is your role in relation to the early childhood system in Illinois?

- What is the role of your organization in the EC system? Please describe your organization, funding, etc.

- What challenges does your organization face in implementing and supporting high-quality ECE programs? How has your organization responded to these challenges?

System Development

- To begin, how would you describe the SECE system in Illinois at this point in time? What are some things that have been put in place in the past decade/years to build IL’s SECE system?

- How would you describe the relationship among the three main types of publicly funded ECE programs in the state—Head Start, child care (CCDF/CCAP), and PFA programs at this point in time? How has this relationship evolved?

- What policies enable collaboration between your agency/organization and other agencies or programs in the SECE system?

- What are the “drivers” for collaboration? (e.g., meet diverse needs of families, improve access for families, improve program quality and accountability, reduce program costs, reduce duplication of services, improve gaps in services, funder requires it)

- How often do you have professional contact with [other SECE organizations]? What is the nature of your contact? How well are these relationships working? How have the frequency and nature of your contacts evolved over time?

Barriers to and Supports for System Integration and Alignment

- What do you see as the primary benefits to collaboration (vs. competition) for families, workforce, program quality, etc.?

- What do you see as some of the drawbacks or disadvantages? (e.g., different quality, eligibility guidelines, staff credentials and qualifications, ratios, class size)

- How can benefits be enhanced and drawbacks minimized?

- What are some of the supports/facilitators vs. challenges/barriers to collaboration? (Probe for federal, state, and local policies, provider factors, and family needs and preferences.)

- What factors make collaboration work? (e.g., personal qualities of people, management skills, communication, problem-solving, finances) What supports are there in terms of workforce training or coaching to improve skills?

Tensions in Collaborations

- There are some natural tensions in collaboration, e.g., a tension between advancing or improving a particular program vs. developing a system of services. Or a tension between increasing supply and access vs. improving quality? Do you agree? Where is the emphasis in current policies and practices? Is there a way to resolve these tensions?

Example of Successful Collaboration

- Can you describe a successful collaboration among ECE providers? How did participating agencies come together? How were responsibilities determined? How did participants define objectives? What makes this a successful collaboration?