Volume 10 Number 2

©The Author(s) 2008

At the Zoo: Kindergartners Reinvent a Dramatic Play Area

Abstract

In a South Dakota early childhood program, children and adults in the kindergarten classroom collaborated to build a “classroom zoo” in support of the children’s pretend play. Creation of the zoo incorporated information about animals and zoos that the children and their families and teachers located in secondary sources such as nonfiction books and the Web site of the San Diego Zoo. Zoo-related activities culminated in a Grand Opening to which families and other classrooms in the center were invited.

Background Information

The Fishback Center for Early Childhood Education is located in Brookings, South Dakota, on the campus of South Dakota State University. The program houses three laboratory preschool classrooms and one kindergarten classroom. At the time of the activities reported in this article, 22 children were enrolled in the toddler lab. Thirty-four children were enrolled in the 3- and 4-year-old classrooms, 38 in the 4- and 5-year-old classrooms, and 22 in the kindergarten classroom. Fishback Center has been accredited by the National Association for the Education of Young Children since 1978.

The threefold mission of the Fishback Center is (1) to be a model inclusive childhood program that ensures optimum experiences for training early childhood teachers, (2) to provide a unique research opportunity for students and faculty, and (3) to serve as a community resource for families. The Center offers an experiential, inquiry-based, negotiated curriculum inspired by the Reggio Emilia philosophy and emphasizing a rich classroom environment and close observation of children’s interactions.

The kindergarten classroom, which is the focus of this article, is part of the Fishback Center as well as a collaborative effort with the Brookings School District. Enrollment is open to anyone in the district; the 22 students are selected through a lottery process. In fall 2007, when the activities describe in this article took place, the classroom population consisted of 9 males and 13 females. Two children were Asian, and the other children were Caucasian. One child’s home language was Dutch, and one child spoke Chinese at home. Classroom staff consisted of one head teacher (Sue Brokmeier) and one assistant teacher, both of whom had been teaching in the kindergarten classroomfor 3 years. The principal author of this report, who worked with Ms. Brokmeier to plan and implement activities related to the zoo, is an assistant professor at South Dakota State University.

The school district’s selected texts and the South Dakota state educational standards are major components for the development of the kindergarten curriculum, but the inquiry approach utilized is similar to that used in the other Fishback Center classrooms. Topics for investigation (ideas, explorations, and projects) emerge through dialogue among children, teachers, and parents.

The daily classroom schedule consists of the following:

| 8:15 | Settle in |

| 8:30 | Morning Meeting/Large Group Discussions |

| 8:45 | Reading |

| 9:15 | Choice Time |

| 10:15 | Writing Workshop |

| 11:00 | Recess |

| 11:30 | Lunch |

| 12:00 | Reading |

| 12:30 | Math |

| 1:00 | Large Group (PE, art, or projects) |

| 1:30 | Centers |

| 2:00 | Dismissal |

Choice time and centers, two components of the overall daily schedule, are the time periods when several areas of the classroom are made available to children. When the children are immersed in project work, center time is still part of the schedule, even though the children may choose not to participate in the different centers because of their high interest in a project.

The morning meeting is an important community building time, to settle issues or to present ideas to the whole group. Large group discussions are used as well when decisions or issues need to be settled. Group decisions are often made through the voting process, which is a part of the classroom culture from the very first day of school. The teacher explains the voting process and begins with “low-risk” votes—for example, the class votes to decide between two books to be read aloud. The book with the most votes is read first, but the other book is read later in the day. The teachers avoid terms such as “winner” and “loser,” although the children sometimes see voting in those terms. The teachers find that the class tends to adopt the mantras to support peers disappointed by the outcome of a vote: “You get what you get and you don’t throw a fit” and “Don’t worry, there are a lot more days of kindergarten.”

Laying the Groundwork

Prior to the start of the school year, Sue (the kindergarten teacher) and I discussed the areas of the curriculum that needed closer observation. Sue expressed concern that the dramatic play area did not seem to support the children’s literacy development the ways she had hoped. She felt that the children did not take “ownership” of incorporating literacy-related items into the dramatic play area by (for example) asking for or including items as books, notepads, menus, etc., to further their play. Some storytelling occurred within the dramatic play area, but the play did not carry over to other areas of the classroom. Sue noted that when teachers introduced literature items and ideas as provocations to the dramatic play area, the children seemed to see them as novelties for a brief time but did not use them for functions of literacy, as she had hoped.

To help identify how literacy might be better incorporated, Sue and I arranged for me to observe her class during choice time two to three mornings per week for 1 hour each day, when we expected children to use the dramatic play area. Sue and I also decided to meet once per week to discuss our observations and findings, determining where we might go next with the children’s ideas.

Even though the incorporation of literature into dramatic play was our main focus, a new concern arose a few weeks after the children arrived, when we observed the children becoming less enthusiastic about playing “house” in the dramatic play area during choice time. The dramatic play center was also part of the afternoon center rotation, so each day two to three children would be assigned to that area. The first rotation of the centers met with success, but the second time the children were assigned to the dramatic play center, grumbling started. Jacob spent much of center time sitting on the steps of the loft. “What’s the matter?” Sue asked. “This is boring,” complained Jacob. “Hmm, the dramatic play area is boring,” Sue replied. “Yeah,” he stated. “Do you think we could change it? Would you want to change it?” Sue asked. While Jacob didn’t offer any specific suggestions for a new setup for the center, he did agree that this would be a good topic to bring to a class meeting. Over the next few days, Sue informally surveyed some of the students about their continued interest in playing “house.” “Jacob thinks we should change the center into something else,” Sue confided. “What do you think?”

Sue suspected that the children had not realized that they could have input into changing part of the classroom; she felt that their experiences may have been in adult-controlled environments. Although she could have simply changed the center herself, she decided to “set the stage” so the children would take ownership of the center.

The Beginning: From Animals to Zoo

Meanwhile, in my observations during choice time, I was seeing several different types of animal play. Some of the children made “leashes” out of plastic chain links and took their classmates, who were pretending to be cats or dogs, out for a “walk.” The children would hook the plastic chain links onto another child’s clothing and walk behind that child, who would crawl on the floor. They would go around the room explaining what type of animal they were following. The children also built “kennels” for the animals in the block area by stacking up blocks under the loft area, especially underneath the stairwell to the loft. The children expanded their imaginative play by discussing with each other what type of animal was in their “kennel” and what their animal needed. I noticed reciprocal leadership and follower abilities emerging—some children wished to be owners of the “kennels,” telling the “animals” what to do, while other children appeared willing to follow the orders given to them. Children would switch roles with each other, signaling that they wanted to change with statements such as, “It’s my turn to be the dog and you can be the walker,” or “It’s been a few minutes. I want to be the dog now.” Children switched roles on a daily basis, with every child participating in the animal play in some manner during the first few weeks.

Figure 1. Susie took Chris for a walk using the plastic chain links.

Sue and I discussed changing the dramatic play area to a pet store or a veterinarian’s office based on our observations of children acting as animals. Sue arranged to have one of the children’s fathers—a veterinarian—speak to the class about his work, potentially sparking the children’s ideas for dramatic play setup. This father’s specialty is large animals, so he brought photographs of cows and horses that he had helped. He also brought his doctor’s bag and demonstrated how several of his instruments worked. Several of the children responded to the veterinarian’s visit with stories of their own experiences with animals. (“I rode a horse once.”) Others remembered getting their “kindergarten shots” and could connect such experiences to how a veterinarian would give shots to animals. The children asked no specific questions about animals or animal care during this visit. Shortly after the visit, I read a book, “Pick a Pet” by Diane Namm to the class, which introduced a pet store, vet, and zoo.

In spite of hearing the information about animals and animal care from the book and the guest speaker, the children still did not convert their interests and ideas into creating a dramatic play area focusing on animals. This was apparent when Sue decided it was time to ask the children to generate a list of possible directions for the dramatic play area to take. During that group discussion, children presented the following ideas for the dramatic play area: a castle, a pet store, a veterinarian’s office, numbers, a library, a dragon pet store, a doctor’s office, a home, a zoo, and a farm. Because it was not feasible to include all of these ideas, Sue suggested taking a vote. The selection process for changing the dramatic play area was perhaps the first “high-stakes” vote of the school year, but the novelty of being able to change the classroom and the enthusiasm for the project may have prevented some of the disappointment that may have been present in other situations. Rather than having strong convictions about what type of dramatic play center they wanted, it appeared that the children were interested in being part of the process of generating ideas and voting; I noted that many children did not vote for their own suggestions. The results of the voting are shown below (initials indicate which child made the suggestion).

Ideas for Our Pretend Play Center: Our Votes

- Castle/Palace (CW, HN, LD) XXXX 4

- Vet’s office (AS, LD) 0

- Pet Store (IR, BR, HV, ZQ, JW, AS, SH, KM) XXX 3

- Numbers (DN) X 1

- Library (AS) X 1

- Dragon Pet Store (GC) XX 2

- Doctor’s Office (TH) X 1

- Home (NR) X 1

- Farm (ZML) 0

- Zoo (GC, ZQ) XXXXXXX 7

The final decision, based on the votes, was to turn the dramatic play area into a zoo. This decision led to several other large group discussions. Sue and I wondered what the zoo should include and how to guide the children toward taking ownership of the process. Sue started recording the children’s ideas as lists and plans that could be revisited as the work continued. Below are two samples.

What Should Be in Our Zoo? Jenny: Pretend animals Sophia: Elephant Shane: Veterinarian Andrew: Ellie (a stuffed elephant that belongs to the Center) Ella: Hippos Brandon: Lions Chris: Fish Payton: Zookeeper James: Sheep Paul: Dogs Liz: Cats Cade: Cages Sophia: Ducks |

Our Plan Bring pretend animals from home Get real wood Use blocks for the crocodiles Make some animals out of paper and wood, play dough, glue, tape, and clay Create signs |

The children began to bring stuffed animals from home. They brought toy giraffes, elephants, whales, snakes, cats, pigs, cows, polar bears, teddy bears, birds, dogs, penguins, rhinos, rabbits, water buffaloes, tigers, lions. The collection grew, but the zoo did not. The animals were stacked on shelves and brought out to play with during choice time.

Moving toward Deeper Understandings

Sue and I discussed ways that children’s involvement in converting the dramatic play area to a “zoo” might include developing deeper understandings of animals, such as being able to sort living from nonliving things, identifying the needs of all living animals, and being able to identify specific animal characteristics and habitats. We also wanted the children to develop greater understanding of what having a zoo might entail, as they moved toward creating one in support of their own dramatic play.

Sue began a unit of study in science that was focused on animals. She read books to the class and introduced new vocabulary such as hibernate, nocturnal, oviparous, and habitats. Some of these books were part of the Macmillan/McGraw-Hill Science Series, while others were teacher picked and read at group meeting time, such as Chickens Aren’t the Only Ones by Ruth Heller. Sue also utilized a few of the Harcourt Reading Series books related to animals during reading time. Other nonfiction and fiction books about animals were already present in the classroom (see the book list at the end of the article).

New vocabulary related to animals and zoos emerged during group meetings and reading. A new word, such as omnivorous, would be said aloud to the class, reviewed again by revisiting the word or asking questions related to its definition, and then supported by reports the children prepared to present later in the month. The reports were part of a homework assignment that Sue created in order to bring more family involvement into the investigation. She asked each child to find information on an animal of his or her choice and to share that information with the class. This assignment allowed individual children and their family members/parents to self-select one animal and to answer a set of questions about it, using multiple resources of their choice. The questions on the report included the following:

- "What is the name of your animal?"

- "Where does your animal live?"

- "How many legs does your animal have?"

- "What kind of covering does your animal have?" (shell, skin, fur, feather, scales)

- "What does your animal like to eat?"

- "Is your animal oviparous?"

- "Does your animal hibernate?"

- "Does the baby look like its mother?" (for example, giraffes do, frogs do not)

- "Is your animal smaller than your hand?"

- "On another piece of paper, draw a picture of your animal."

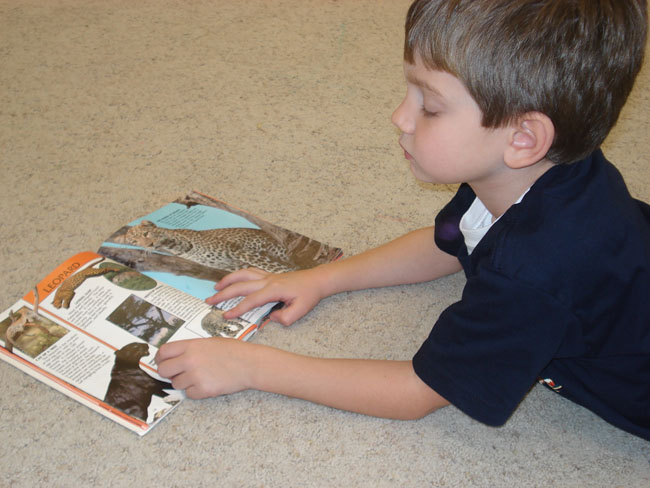

During center time, Sue also worked with small groups of children to help them fashion animals out of clay. Each group had 30 minutes with the teacher, but the children could continue to work on their animals over the next few days, if they chose. Most of the children took great care with their creations and appeared to pay more attention to the unique characteristics of their animal than they had prior to their study of animals. For example, Molly, in the picture below, reviewed a nonfiction book of wild animals while creating her cheetah out of clay. She noticed the head, body, and leg size proportions, along with the cheetah’s spots, which she created by poking small holes into the clay sculpture. She also created a giraffe picture, indicating the presence of giraffes after reviewing the same wild animal book. Brandon attempted to create an elephant. His creation had several weak spots, but he was determined to have a trunk and ears on his clay animal and worked until his elephant stood independently. Chris, on the other hand, was content to shape his clay in just a few minutes. He said he was making a dog, but he decided it looked like a fish, so a fish it remained.

Figure 2. Molly’s clay cheetah model was based on illustrations in a book about wild animals.

Figure 3. Children made sketches for signs indicating the presence of the giraffes after looking at a book about wild animals.

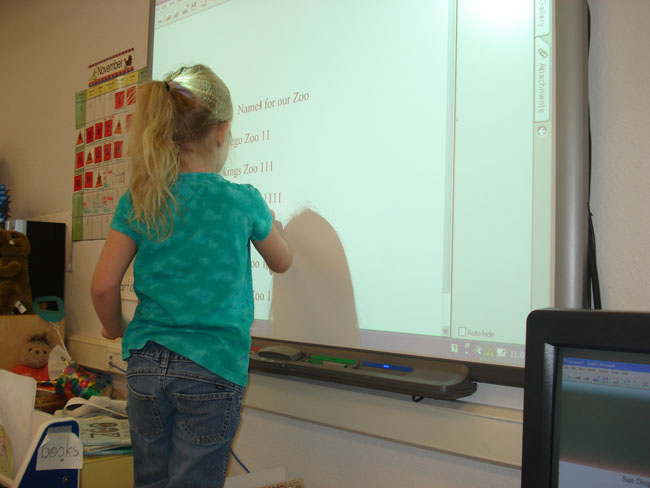

Sue also found information about zoos on a variety of Web sites, and using a projected interactive whiteboard called a “Smartboard” with the entire class, she provided a wide-screen virtual tour view of the San Diego Zoo (http://www.sandiegozoo.org). The children were especially excited to hear sounds of animals and view the pictures and brief descriptive summaries of each animal on the Web site. They often asked to visit the “Animal Bytes” site again during choice time (http://animals.sandiegozoo.org/).

Sue and I both noted that children were discussing their prior experiences of being at a zoo and pinpointing similarities and differences among animals on the Web site during choice time. In these conversations, children utilized terms such as rain forest and jungle (which they used interchangeably), habitats, and environments. They began to be able to label the stuffed animals within the classroom to some extent. For example, a few of the boys labeled the snakes as cobras or pythons, indicating that these were types of snakes that needed trees to climb and water for swimming and drinking. Other children found differences in their knowledge base when some children labeled the orca a “killer whale.”

To further enhance the children’s vocabulary, Sue wrote different terms onto the marker board during morning meeting times. She used open-ended questions, finding out more about the children’s knowledge base by asking about their prior experiences. Her questions included, “What did you see at the zoo? What did the animals look like? What animals belong in the zoo?” She continued to provide new information and assist children in finding answers to their questions, such as “What are the differences and similarities between the orca and killer whale?” and “What is the difference between a rain forest and jungle?” Even though Sue knew that some of the children’s misunderstandings (for example, the idea that koalas are bears) would be addressed and their questions answered in due time, she decided to address specific questions or misunderstandings during group time, and to offer and use nonfiction books, Web sites, and prior knowledge (the children’s and her own) to further the children’s understandings. For example, after finding out the children’s ideas and conclusions, she made them aware that different terms, such as killer whale and orca, or jungle and tropic rain forest, were used interchangeably in society. The children understood that even though they might be using different terms, the terms had the same meaning.

Figure 4. Chris used a book to further his understanding about cheetahs.

By this time, some of the children were beginning to create homes for the stuffed animals they had brought. The block area underneath the loft in particular was a popular place to keep the animals, but it was too small to accommodate all of the animals, and children began fighting over the space. Sue called a meeting, and ultimately the group decided that they needed to turn the whole classroom into a zoo. Children initiated the discussion by telling one another that they needed to sort the toy animals into groups based on different animal species and then to place the animals in different areas. Sue and I believe that the children initiated this idea based on their prior experience of visiting zoos. Several of the children began this process (for example, all bears were placed into one pile) during choice time.

Zoo Project Conversation Log 10-24-07

Several of the students are sorting the stuffed animals to help decide how many different cages the class will need to make for their zoo.

Sophia: We’re sorting them! Look!

Molly: Everything can’t be by itself.

Sophia: I can count them. (She starts counting the bears and Brandon joins in.)

Brandon: .10—10 of them. I know how many bears.

Molly: I can count for cages. (She counts the groups of animals.) 1 cage, 2 cages. (She stops when she sees a koala.) This is a koala bear. It should go by the other bears.

Brandon: That means there’s 11 bears!

Figure 6. Children sorted the toy bears into one pile.

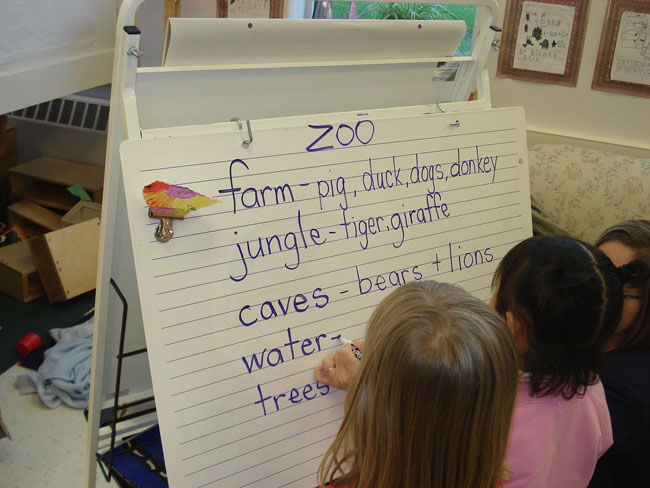

Then, writing on a large marker board, the children listed different habitats, such as jungle, farm, caves, water area, and tree area, and further discussed and sorted the animals into more specific groups, based on their understandings of animals’ environmental needs. As they sorted the animals, some children wrote down where they thoughtthe animals belonged onto a large marker board. Their judgments were based on a combination of factors: what they had personally experienced when visiting one of the habitats, what they learned through the classroom’s nonfiction books and the San Diego Zoo Web site, and what they heard about others’ experiences. They placed pigs, ducks, dogs, and donkeys into the farm habitat, knowing from their own experiences and that of others in the class that those animals belonged at a farm. To reinforce the decision making about animals and habitats, Sue revisited the San Diego Zoo Web site with the children using the Smartboard and referred children back to nonfiction books to find answers to their questions.

Figure 7. Children wrote on the marker board to record how they were sorting the animals by what they thought would be the appropriate environment or habitat.

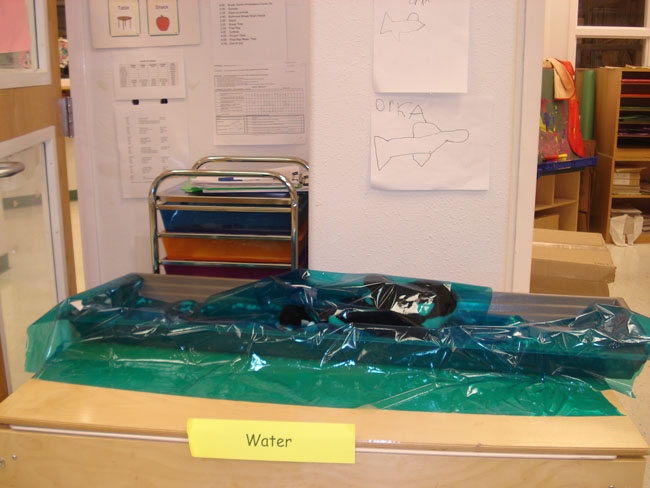

Soon the children decided that they were ready to create habitats for the animals. Sue posed the question, “How many habitats do we need?” Even though the children had initially discussed farm, jungle, caves, water area, and tree area as possible habitats, several of them stated that the zoo also needed cages. She asked each child to sign up to help build one of the habitats/cages. Then she met with each group to see what supplies they thought they would need and to designate a location in the classroom for their habitat. Many attempts and much problem solving occurred as children used a variety of materials—clay, play dough, tape, glue, cardboard, tin foil, and craft sticks—in attempts to create cages and fences that would stand up without support.

Other children used large wooden blocks to provide barriers for animal cages. A few children used textile products such as blue and white plastic wrap for “ice and snow,” while others made trees, vines, and leaves from cardboard tubes, construction paper, and glue. As they worked to transform the room into a zoo, children covered shelves and tables, taped “trees” to the loft, and even covered the wooden play kitchen set with paper. The stuffed animals were placed into their new homes, but the clay animals were kept on a separate shelf for safety.

Figure 8. Sue met with small groups of children to help with planning.

Figure 9. Cade and Molly created small cages out of craft sticks.

Figure 10. Sections of blue and white plastic wrap were used for the icebergs habitat.

Figure 11. The rain forest was created with construction paper and cardboard tubes.

Figure 12. Children created the water area for the orca.

Figure 13. Children used blocks to form the “bear cage.”

Figure 14. Children used aluminum foil as cage bars, green construction paper as the grassy areas, and blue construction paper as the water areas.

Children began spontaneously putting up signs for the zoo. When Sue noticed that Ella, one of the girls, had started making signs for “Kindergarten Zoo,” she realized that naming the zoo was something that should include everyone. The children suggested names and eventually voted to name their project “SDSU Zoo.”

Figure 15. Sophia used the Smartboard to cast her vote for the name of the zoo.

When the teachers felt that the children’s hard work was ready to share with friends and families, they designated November 29 as the day that the zoo would be open. The teachers helped the children write invitations to their families. Sue made copies of the invitations and distributed them to the preschool and other people in the South Dakota State University Early Childhood Education Department. The children made maps of the room so the visitors would know where the exhibits were located.

Figure 16. Andrew drew a map of the SDSU Zoo.

Checking to see whether the class was ready for visitors to the SDSU Zoo, Sue revisited the original plan with the children. During the conversation, they realized that the zoo still had no veterinarians or zookeepers. Some of the children planned what those roles should entail. The children who wished to be zookeepers indicated their specific duties during a planning meeting.

| Zookeepers | Things Zookeepers Do |

|

|

BR: We need zookeeper clothes. The children in the Out-of-School Time Program could make some hats.

NR: I’ll take care of monkeys.

DN: I’ll do the bears’ cave.

CW: I want the donkey (Molly).

HN, EF, IR, and JW: We want the elephants!

SH: Sophia (bear).

ZQ: I’ll help the squirrels.

BR: I’ll do the giraffes.What We Need

- hats

- sign

- food

Three of the girls decided they would rather be animals than tour guides or zookeepers. They made masks out of paper plates and yarn and created signs such as, “Wild Donkey—Watch out!” for their specific cages. The girls also wanted to wear costumes that were comfortable and would allow them to move freely. Sue talked with the children’s parents, assuring them and the children that dressing in a solid color would suffice. One of the boys, Payton, insisted on being a ticket taker, and several children helped him make tickets to have on hand.

I helped several of the boys in the room record their own individualized animal sounds on a tape recorder so our zoo would have sound bytes like the San Diego Zoo’s Web site. I would state an animal’s name, and the boys collaboratively created that animal’s sounds for the recording. The extent of the boys’ knowledge of animals and the sounds they make was apparent. For example, when I stated, “Monkeys” for the recording, Chris asked, “What kind of monkey, Teacher? There are different kinds.”

The day before the zoo opened, the class practiced their roles and discussed how to handle the visitors.

Figure 17. Molly acted as a wild donkey while zookeeper Cade tried to clean her cage.

Grand Opening of the SDSU Zoo

Over 150 people attended the grand opening of the SDSU Zoo, including 100 preschool children and teachers, as well 50 family members. Every child had at least one family member visit the zoo. The teachers had scheduled the zoo to be opened at times convenient for families—at drop-off time, during the noon hour, and at the end of the day. The preschool teachers made appointments for their classes to visit so it would be easier to manage the number of visitors.

As the children led tours or acted out various roles, they welcomed the visitors and demonstrated what they understood about zoos and animals after their research.

Graham: Welcome to our zoo.

Shane: Watch out! There’s a donkey in that cage and he’s wild!

Chris (animal sound manager): Come listen to the animals sounds we made.

Sophia: We had lots of bears so our cave is pretty big.

Cade: I am a zookeeper so I take care of the animals. I clean the cages too.

Figure 18. A sign marked the zoo’s entrance.

Figure 19. One hundred fifty teachers, parents, and children attended the “Grand Zoo Opening.”

The children appeared to take pride in what they had done and to have a sense of ownership about what they had created together. Sue mentioned that her only job during the event was to direct traffic flow for the guests while the children did the remainder of the activities. The children were eager to show the visitors what they had made and seemed proud that their families and friends had come to support them.

Parents’ Comments on the Zoo

One parent of a child who had participated in zoo activities remarked, “My son decided to make a zoo in his room. It was great. We even did our own map. The learning that took place further enhanced my child’s cognitive abilities. Way to go!” Another parent reported, “My child created animal habitats at home, including drawing animals. She has definitely improved with her problem solving as well. She tries several ways to fix a problem and then decides upon the best.”

Reflections on Creating the SDSU Zoo

Reflections from Sue Brokmeier, Kindergarten Teacher

Had I just chosen to turn the dramatic play into a vet’s office instead of involving the children in the process, we would not have had nearly such a successful experience. The children’s ownership of the project kept them motivated and engaged. I am amazed that such a common theme—pretending to be animals—could turn out to be so rich. Children accepted one another’s ideas well—the jungle trees were different in sizes and the signs and maps were also unique, and yet all children were okay with them. The children’s literacy and math skills were strengthened; their problem-solving abilities were impressive. I was delighted with their interest in new vocabulary and their desire to read nonfiction books. Yet, it wasn’t just their cognitive skills that were addressed. Their social and creative skills were also greatly enhanced. You know the children are excited about a project when they choose to work on it during their choice time!

Reflections from Mary Bowne

Sue and I saw the invaluable inquiry-based learning that took place during the investigation of animals and zoos in this kindergarten class. We saw evidence that each of the 22 children in the class was highly motivated and involved in a number of activities.

Increasing the children’s opportunities for literacy during play was initially the main focus of this research project. During their work on the SDSU Zoo, the children expanded their literacy and language development in several ways. They utilized fiction and nonfiction books to support their questions about animals and zoos. They also used verbal and nonverbal language techniques to ask questions, to communicate their ideas, and to act as certain animals. The children also demonstrated writing skills as they communicated their ideas about different aspects of their investigation to others. They also utilized computer technology, such as the San Diego Zoo Web site, to further their knowledge of certain animals.

In addition to their literacy learning, the children’s academic skills were strengthened through authentic tasks such as sorting, classifying, and counting the different animals. The children also utilized research techniques and knowledge of how to use secondary sources to find information about animal life, including habitats, lifestyles, and environmental needs. They created “masterpieces of art”: using clay to create animals, drawing pictures of animals, creating costumes and masks to resemble specific animals, and creating representations of habitats from everyday materials, showing their awareness of the needs of each animal.

The scope of the zoo activities was broad enough to incorporate the range of interests and multiple intelligences that the children brought to the process. The fact that everyone came together with a common interest and formed common goals for the creation of this project created a strong sense of community in the classroom. The children were able to feel ownership of the process and the results of their work. The curriculum was truly negotiated between the children and the teacher; the negotiation occurred through listening and observing, through opening and sustaining dialogue, and through overall reflection.

Author Information

Mary Bowne is an assistant professor at South Dakota State University where she teaches undergraduate courses and conducts research and service activities.

Mary BowneBox 2218

South Dakota State University

Brookings, SD 57007

Email: mary.bowne@sdstate.edu

Sue Brokmeier is head teacher of the kindergarten classroom at the Fishback Center for Early Childhood Education located in Brookings, South Dakota, on the campus of South Dakota State University.

Sue BrokmeierBox 2218

South Dakota State University

Brookings, SD 57007

Email: sue.brockmeier@sdstate.edu

Appendix A

Literature Resources

Andreae, Giles. (2002). Rumble in the jungle. David Wojtowycz (Illus.). Wilton, CT: Tiger Tales.

Carle, Eric. (1987). A house for hermit crab. New York: Aladdin Paperbacks.

Carle, Eric. (2000). Does a kangaroo have a mother, too? New York: HarperCollins.

Gibbons, Gail. (1987). Zoo. New York: T.Y. Crowell.

Harter, Debbie. (2004). Walking through the jungle. Cambridge, MA: Barefoot Books.

Heller, Ruth. (1981). Chickens aren’t the only ones. New York: Grosset & Dunlap.

Matero, Robert. (2001). Reptiles. Vero Beach, FL: Rourke Publishing.

McKee, David. (1968). Elmer. New York: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Books.

Namm, Diane. (2004). Pick a pet. New York: Children’s Press.

Rathmann, Peggy. (1994). Good night, Gorilla. New York: Putnam.

Seuss Dr. (1950). If I ran the zoo. New York: Random House.

Van Laan, Nancy. (1998). So say the little monkeys (Yumi Heo, Illus.). New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers.

Wexo, John Bonnett. (2008). Zoobooks Magazine. http://www.zoobooks.com/.

Appendix B

Reading |

|

| K.R.1.3 | Students can comprehend and use vocabulary from text read aloud. |

| K.R.2.3 | Students can comprehend and respond to text read aloud. |

| K.R.3.1 | Students can identify concepts of print in text. |

Writing |

|

| K.W.1.1 | Students can draw a picture and write a simple sentence about the picture. |

| K.W.1.2 | Students are able to use pictures and words to tell a story. |

| K.W.1.3 | Students are able to retell or restate what has been heard or seen. |

| K.W.1.9 | Students are able to write notes to classmates and family members. |

Speaking |

|

| K.S.1.6 | Students are able to follow simple rules for conversations (example: taking turns, listening). |

Math |

|

| K.A.2.1 | Students are able to compare collections of objects to determine more, less, and equal (greater than and less than). |

| K.A.4.2 | Students are about to sort and classify objects according to one attribute. |

Technology |

|

| K.IL.5.2 | Recognize that information can be represented in a variety of ways. |

| K.S.1.1 | Demonstrate respect for the work of others. |

Science |

|

| K.P.1.1 | Students are able to use senses to describe solid objects in terms of physical attributes. |

| K.L.1.1 | Students are able to sort living from non-living things. |

| K.L.1.2 | Students are able to describe the basic needs of living organisms. |

Social Studies |

|

| K.G.1.1 | Students are able to use map colors to recognize land and water. |

| K.G.1.2 | Students are able to compare the globe and a map as models of the Earth. |

| K.E.1.1 | Students are able to identify occupations with simple descriptions of work. |

| K.C.1.1 | Students are able to recognize the important actions required in demonstrating citizenship: respecting roles of members and leaders in a group; sharing responsibilities in a group; identifying ways to help others; respecting the individual right to express an opinion; and acknowledging that people think and act differently. |