Volume 7 Number 2

©The Author(s) 2005

Early Childhood Education as Risky Business: Going Beyond What's "Safe" to Discovering What's Possible

Abstract

Much has been learned about the possibilities of early childhood education from nations that have long invested in high-quality early care and educational programs. These new understandings are now being used by U.S. early childhood advocates to help parents, policy makers, and others better understand children's vast learning potentials, to acknowledge the deep intellectual work of teachers, and to recognize the rights of parents to help determine the essential features of a challenging and beneficial early childhood curriculum. What is less well acknowledged are cross-cultural insights into the potentials of a "risk-rich" curriculum, one in which both adults and children explore new topics and unfamiliar terrains, including those traditionally identified as developmentally inappropriate and beyond the reach of young children. In this article, the potentials of a "risk-rich" curriculum are explored using examples from the cross-cultural research literature as well as two classrooms of young children—one of 3- and 4-year-olds, the others from a kindergarten class. Teachers' reflections on what they learned about themselves and the children they teach are presented as they reveal untapped potentials of early childhood settings as sites for new discoveries and new relationships.

Introduction

In her keynote address at the recent European Early Childhood Education Research Association conference in Dublin, Noirin Hayes (2005) challenged the audience to reconsider some of the many ways that adults have interpreted their roles in the care and education of young children. She urged those who would prioritize adult expertise over children's curiosities and understandings to explore alternative interpretations of professionalism, and she called for a "nurturing" pedagogy that is interactive, dynamic, ethical, educational, and caring. She linked her critique of education-as-knowledge-transfer to what Yeats described as a "filling of the pail," and she echoed Dewey's admonition (1926) to attend to children "living in the present"-not as a proverbial turn of phrase but as an incontrovertible fact (Hayes, 2005). Her remarks resonate with a litany of progressive and postmodern critiques of overly standardized and controlled early childhood education. It was when she called for environments for children that are "respectful, reflective, and risk-rich" [italics added] that she moved squarely inside classroom walls and into the arena of teacher decision making. The purpose of this article is to explore the nature and possibilities of such a "risk-rich" environment as it might expand adult and child understandings of each other and the world(s) in which we live.

Cultural Interpretations of Early Childhood Environments as Safe Havens

It is well established that views of high-quality early childhood environments, reasonable and attainable curriculum goals, and developmentally appropriate pedagogy vary as a function of cultural values, beliefs, and goals (New, 1999). And yet few would argue that one of teachers' primary responsibilities-wherever in the world they might be-is to insure that the early childhood environment is safe for children and that potential risks are anticipated and eliminated. Children's physical safety-including protection from hot water, from exposed electrical outlets, from falling down stairs-is a primary focus of state licensing standards in the United States. Children's emotional security-typically defined as avoidance of emotional distress as well as the presence of feelings of belonging and secure attachment relationships-has been identified repeatedly as an essential element of a high-quality early childhood environment. What is less often acknowledged is that cultures also have diverse and sometimes conflicting interpretations of what is safe for children and what constitutes an unwarranted risk. Diverse interpretations of practices that might place children at risk are associated with variations in the ecologies of early childhood, including cultural differences in what is regarded as necessary, appropriate, and desirable for children's early learning and development.

Risks or Reasonable Practice?

Some early childhood practices defined as risks from one cultural perspective are regarded as sensible child care or educational practices in another. For example, American educators express surprise upon learning that children in Scandinavian countries are allowed to roam outside for long periods of time, often in weather that would send us scurrying back into the warm dry classroom. Yet enjoying the out-of-doors and learning to tolerate and even appreciate all sorts of weather conditions are seen as reasonable values to instill in young children by means of educational practices deemed appropriate in cultural settings where fears of child molesters and liability suits are uncommon and pride in the national landscape is widespread. Italian interpretations of good health preclude purposeful exposure to inclement weather, and yet teachers in this southern European nation regard some forms of risk taking as highly appropriate for young children. Visitors to Reggio Emilia are open-mouthed when they see 5-year-olds ladling hot soup into their classmates' bowls or 4-year-olds atop the tall climbing apparatus outside or swinging on the hanging rope ladder attached to the classroom ceiling. These practices suggest that Italian early childhood educators, like their Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish colleagues, have fewer concerns than do Americans about potential litigation if a child has an accident. These Italian practices also reflect teachers' beliefs that children have the right to engage in physical activities that test their developing motor and critical thinking skills and that "children generally know when they've gone far enough; they are careful because they don't want to get hurt."

Risks Worth Taking

Some cultural practices acknowledge risks but assess them as preferable to the alternative(s). Japanese practices that permit young children to monitor classroom behavior (Lewis, 1995) and resolve conflicts (Tobin, Wu, & Davidson, 1989)-with no mediation on the part of the teacher-are rejected by many U.S. educators as inappropriate and unreasonable expectations of young children. And yet Japanese educators defend such practices as essential to helping children learn how to regulate their behaviors and emotions and to work effectively and constructively as a peer group. Other cultural practices-whether leaving the Danish infant to nap outside in an open crib during the winter, permitting the young Norwegian child to use a sharp knife to whittle wooden sticks (New & Akslen, 2005; see Fig. 1), or allowing the Japanese child to repeatedly engage in physically aggressive and hurtful behavior-are decried by some cultural outsiders as patently dangerous and beyond the pale of professionalism (Tobin, 2005). And yet most teachers and parents in these cultural settings agree that such practices are consistent with goals they have established for children's early educational experiences and beliefs about how children learn.

Figure 1. Norwegian child using sharp knife to whittle.

When Playing It Safe Puts Children at Risk

There are many ways to analyze such cultural diversity in risk taking, the most obvious of which is to consider the role of the larger sociocultural context in its definition. If the social world of young Japanese children is densely populated and places a premium on self-control, it might be risky if schools didn't allow some conflicts; how else can children learn early to manage their own behavior and work and live peacefully with others? A similar case can be made for helping Scandinavian children learn how to engage with physically demanding environments. If there is little respite from the long winter months, it seems reasonable that teachers would encourage activities that promote a love of adventure and an indifference to inclement weather, surely preferable to the idea that children and families might otherwise spend most of their lives indoors.

Other cultural practices that involve risk taking seem to be based on another sort of rationale-one that has more to do with how adults view children and interpret the purposes of an early childhood education than with explicit environmental contingencies. Some of our colleagues around the world even go so far as to suggest that the U.S. emphasis on keeping children safe comes at a cost-that of unduly prohibiting children's active engagement with the physical and social world.

Where Did All the Flowers Go?

The image of Norwegian children playing in a field next to the cow farm reminds us of what children in the United States now rarely do. Traditional images of an ideal U.S. early childhood are replete with depictions of trees to climb, creeks to explore, and home or neighborhood hide-a-ways where children can gather to play make-believe. Regardless of whether or not such activities were ever available to all children or only those of middle-income households in safe suburban neighborhoods, it is certainly the case that such experiences are now rarely encouraged or even allowed in contemporary U.S. early childhood settings. Whether out of fears that children will actually come to serious harm or, more likely, to avoid accusations of irresponsibility, teachers now maintain constant supervision over children's activities even as they discourage or avoid potentially "unsafe" activities. Once-standard field trips are increasingly seen as "taking a chance" with transportation and more open and/or public environments where "anything could happen." Such broadened interpretations of what might be dangerous may be unavoidable in a litigious society such as the United States; they also prohibit children's physical activity as well as their opportunities to participate in and learn from the surrounding community. As such, increased emphasis on the avoidance of risk may limit the very sorts of experiences long held to be part of a healthy and happy early childhood.

Playing It Safe with the Status Quo

A more subtle form of "playing it safe" may also preclude children from having valuable learning experiences. Readiness screening that keeps children out of early childhood programs avoids the risks that come from working with a diverse classroom of learners and increases another sort of risk by effectively shutting some children out of the environment in which they might have acquired the skills and knowledge they lacked. Standardized curriculum goals may also contribute to children's "at-risk" status, whether through failure to ascertain and then build upon the child's prior knowledge and experience or by demonstrating indifference to family values and cultural traditions. For example, an increased (and federally mandated) emphasis on English-based literacy experiences discouraged Latino parents from enrolling their children in the Head Start programs for which they were eligible (Fuller, Eggers-Pierola, Holloway, Liang, & Rambaud, 1996). Still another way in which children may not get what they need is when narrow interpretations of an age-appropriate curriculum fail to acknowledge children's strong predispositions to learn, to make sense of their world, and to "reason facilely with the knowledge they have" (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 1999).

Going Out on a Limb to Secure a Better View of Children and an Early Childhood Education

In the second half of this article, we share some of our own experiences with "risk-rich" classrooms as they validate our belief in the unavoidable need for teachers to take risks if they are to respond authentically to children's ideas, curiosities, and understandings. We are persuaded by the burgeoning literature that challenges canned curriculum and formulaic teaching. We are also encouraged by the courage of others who have looked more deliberately and more critically at early childhood education as a space where children and adults can learn together. Vivian Paley's mandate—you can't say you can't play-comes to mind, going as she did against decades of a cherished tradition of free play (Paley, 1992). We are inspired by Italian early childhood educators, including those in Naples, who invited disgruntled grandparents to teach the children how to make wine; and teachers in Reggio Emilia, who challenged parents convinced that their children didn't really know what was going on in the Persian Gulf War. In each of these cases, teachers took a chance, responding to real concerns with creativity and courage. The resulting classroom cultures were neither predetermined nor "safe" in any traditional sense of the word, and yet everyone-adults as well as children-benefited from their risk-rich qualities.

The two stories that follow took place in a university laboratory school setting where university professors, students, parents, children, and their classroom teachers daily cross paths. The setting is filled with colleagues committed to principles of diversity, inclusion, and-more recently-the practice of collaborative inquiry. Our own understandings of a "risk-rich" curriculum grew in this context, inspired, in one case, by children's curiosities about a large dog with grey eyes and floppy ears and, in the other, by children's frustrations at trying to resolve a seemingly irreconcilable conflict in a way that would "be fair to everybody." Both stories began in a state of uncertainty. As the two projects grew over time, they each became contexts in which 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds learned alongside their teachers about how to make sense of and contribute to a world that is not always fun, nor fair.

"Can You Draw Me a Map to the Cemetery?"

This curriculum project didn't start out as a project at all. In fact, it was a chance encounter that lead to a teacher's decision to allow children to develop a relationship with a sick dog-a decision that seemed sure to lead to a sad ending. David, the teacher in this classroom of 3- and 4-year-old children, explains how this began:

One cold morning last January, 4-year-old Michael arrived at the door of our laboratory school just as one of the university professors, accompanied by her dog, Tucker, was heading to her office. Michael is blind, and so his mother told him a dog was also entering the building. Michael then sought out the dog, asked his name, and inquired whether Tucker was a seeing-eye dog. The professor-Ann-explained that Tucker's only responsibilities were to play. Ann and Tucker soon went on to her office and Michael joined his classmates, sharing his experience with me and his other teachers and peers. I was inspired by Michael's story to follow up with Ann. She explained that Tucker had been diagnosed with cancer and he often accompanied her to work, where he could be found resting in her office or, less often, running around the campus. We discussed the possibility of facilitating a relationship between Tucker and the children in my preschool class, and Ann reassured me that the dog was not contagious and had enough energy to visit and play with the children.

But why would a preschool teacher purposefully encourage children to develop a relationship with a sick dog-one not expected to survive his illness? David explains the sources of his decision making, including his interpretations of children's competencies and his responsibilities as their teacher:

As a teacher, I have always used the children's interests to generate curriculum ideas. Developing a relationship with Tucker seemed to open up many potential activities to support the children's development. Letter writing, cooking, and scientific explorations related to dogs were a few of my thoughts.

This confidence in children and the potentials of an emergent curriculum did not assuage all of David's concerns, however. He was fully aware of the possibility of less-desirable outcomes:

In spite of my initial enthusiasm, I was troubled by the potential risks of allowing children to become emotionally attached to an animal who might die in the near future. I wanted to protect them from the possibility of emotional pain, but I also felt strongly about helping them expand their understandings of the world by developing a relationship with Tucker.

It was ultimately the support that David felt from the larger school culture, including the educational goals set by children's parents, that encouraged him to risk inviting Tucker into the children's school lives:

In retrospect, I think I chose to pursue a relationship with Tucker for the children because this decision seemed consistent with the culture of my classroom and school and our commitment to diversity and inclusion. The children came from diverse cultural backgrounds, with a range of abilities and skills as well as social, emotional, physical, and learning dispositions. Their parents had already decided to send their children to a school that values inclusion and diversity, and wanted their children to learn that everyone has "special needs," and to learn how to be both accepting and caring of others within a context of an inclusive setting. Teaching in a supportive community that respects difference and individual needs helped convince me that it was worth the risk to construct a space for developing a relationship with a sick dog. I was confident that Tucker would provide a context in which the children could learn about each other's individual needs even as Tucker also offered them an opportunity to learn about the needs of a dog.

As David and the children developed a relationship with Tucker, they revealed their capacities to nurture, to look beyond the presence of illness, and to derive pleasure in caring for others:

We started our relationship by visiting Tucker in small groups and occasionally by writing letters to Tucker. I chose to tell the children that Tucker was sick, but I didn't go into detail because one child had cancer as an infant. The children didn't ask questions when Tucker turned yellow from jaundice, nor did they seem to notice his lethargic behavior after receiving chemotherapy. Instead, they focused on Tucker as a new friend. While lying down next to Tucker, the children would say, "Tucker gets excited when he sees us. He wags his tail. He is soft with thick fur," and "He licks us when we visit, that's his way of saying hello. We like lying down with him; he likes his tummy rubbed, and he likes putting balls in his mouth."

Figure 2. Children petting Tucker.

When the children were told that he wasn't eating his food, they cooked homemade dog biscuits. When they delivered them to him, they shrieked with delight when he greedily ate the biscuits.

David used children's concerns for and pleasure in Tucker to promote alternative forms of communication and connection:

Sometimes Tucker was not in Ann's office, and so the children began to look for other ways to communicate with him. They created a "Tucker" mailbox and made frequent visits to deliver the mail. Sometimes the children received a letter in response, which initiated a discussion about whether Tucker "really" knew how to write. Some children explained, "Tucker talks to us by showing us what he wants." Other children proposed that Tucker told Ann what to write. Over several weeks, the children developed a loving and caring relationship with Tucker, and his role in the classroom expanded.

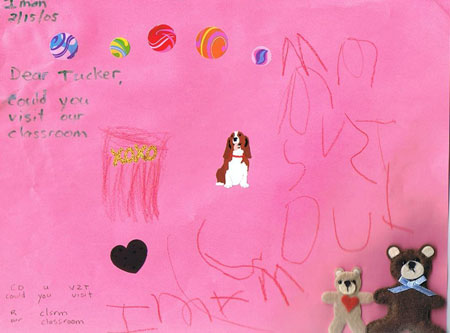

The letter writing was done by boys and girls, including some who had only begun to demonstrate their emerging literacy understandings (Figs. 3 & 4).

Figure 3. A letter to Tucker.

Figure 4. Grace's letter to Tucker.

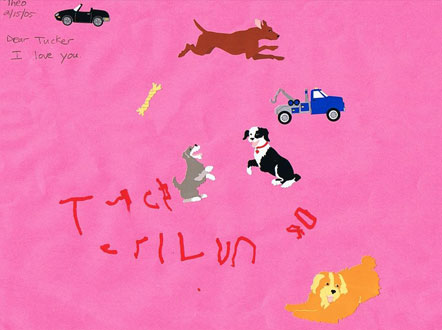

Sometimes stickers took the place of words as children looked for ways to share their ideas and their affection with Tucker (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Letter with stickers instead of words.

Tucker often served as a catalyst for other ideas and concerns. For example, children wrote a fictional story about Tucker that reflected their own experiences and interests. The story described how Ann cared for Tucker when he was sick or hurt-paralleling real experiences about how their parents help them when they are sick. The children illustrated the story by adding tactile objects that represented the storyline. When Tucker was hurt in the story, they added a bandage to that page. The tactile objects supported Michael, the child who is blind, by serving as cues to the story, and the children also thought Tucker would enjoy the objects.

As Tucker's role in the life of the classroom increased, David's initial concerns were mediated by his growing appreciation of children's capacities to relate, to communicate, and to be creatively caring. Letters to Tucker also began to include consideration of Michael's special needs, as Tucker's name was also written in Braille (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Letter with braille in the upper right-hand corner.

Our relationship with Tucker was exciting, and I pushed aside my original concerns about the risks of their growing attachment as I observed how the children related to Tucker as a peer and how they incorporated him into their daily life. Repeatedly, Tucker served as a reference point for their efforts to make sense of their world. At snack time, they thought about Tucker by planning a time to make more dog biscuits. While playing outside, the children thought about sharing the playground with Tucker, and at group time, they made a space for Tucker to sit. Their curiosity to learn about themselves and their relationship with Tucker was the foundation of many role-playing experiences.

David was also reminded of children's powerful drive to make sense of what they are experiencing by incorporating real-life themes into their dramatic play:

While role playing various themes, the children incorporated Tucker as a coveted role. A "pretend" Tucker was frequently a part of doctor role playing."Bow-wow, it hurts," said Tucker. His "mother" then helps him and takes him to the doctor."He has an ear infection," says the pretend doctor. While engaged in restaurant play, the children pretended that "Tucker ate one hundred pizzas, one hundred macaronis, and eighty squashes." During pretend play, one child said, "We made everything for Tucker. He said, 'RUFF' which means thank you!"

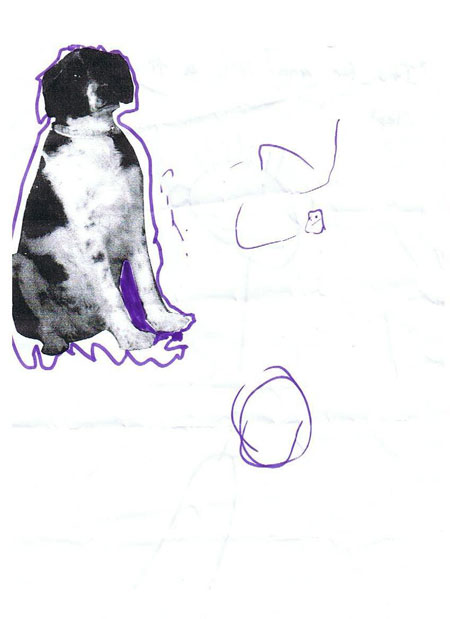

Tucker's presence was found throughout the classroom, in children's conversations, their drawings, their play (Fig. 7). When it was time for the school picture to be taken, there was no question-of course Tucker had to be in the photograph!

Figure 7. A photograph of Tucker in a drawing.

Some of the children who had difficulty verbally expressing their thoughts were able to discuss their feelings and ideas related to Tucker. Inviting Tucker into our lives was an enriching experience for all.

As David had anticipated, however, the loving relationship with Tucker could not deter the inevitable decline in his health:

The children continued to play with, care for, think about, and talk about Tucker throughout the winter and early spring. The initial relationship, sparked by curiosity, eventually turned into a strong and vibrant friendship. When I learned of Tucker's death in late May, I dreaded telling the children and parents. The children trusted their school as a safe and predictable environment, and I knew that the parents might be distressed that their children were exposed to emotional pain. I was sad for Ann and the children, and I felt a deep sense of loss for Tucker. My emotional response led me to question my judgment about taking the risk of having the children befriend a sick dog, and so I waited two days before telling them. I needed time to process Tucker's death and think about how and when to tell the children. Writing a letter to parents helped me to put my own complex feelings into words. As I described how they might want to support their children, I also validated my risk taking when I described the many ways we had learned from and with Tucker. "We have written letters to him, made him dog biscuits, and visited him in Ann's office. Tucker even visited us a few times. The children have truly developed a special bond with Tucker—he is even in our class photo!"

So now David took a second chance-to tell the children the truth. Although he knew that he was taking a risk in discussing Tucker's death, he was not willing to risk their loss of trust by hiding the sad news about their friend Tucker:

Two days after Tucker's death, I anxiously gathered the children at morning meeting and told them that I had something very important to tell them. My tone of voice created a hush among the children and I said, "I have something sad to tell you." I paused and some children asked, "What?" I said, simply, "Tucker died." Their first response was denial. They all said, "NO! YOU'RE LYING!" They didn't believe me, and one child said they would only believe Ann. They insisted on visiting her office to see if Tucker was gone. I knew Ann was not in her office, but I allowed the children to march down the hall, and they returned unsatisfied when they learned Ann was not at school. Throughout the day, the children talked amongst themselves about whether they believed that Tucker died. They repeatedly asked me if it was true. When the parents picked them up from school, the children told their parents that Tucker died. I was thankful that I had already alerted the parents, and they were able to share the children's sadness and help their children cope with Tucker's death.

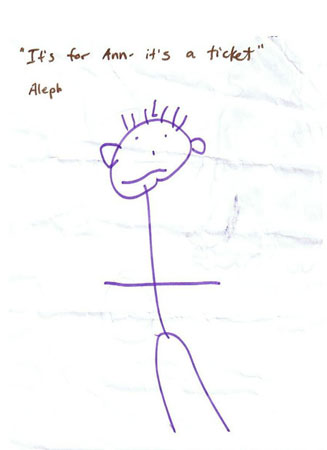

Soon thereafter, the children met with Ann, and she described Tucker's illness and death and her own sadness. The children decided to write a book about Tucker and to construct a papier-mâché model to represent his body (Fig. 8). They were concerned with Ann's welfare and wrote letters to her expressing their grief. One letter invited Ann to come visit them, and a ticket was provided (Fig. 9).

Figure 8. A papier-mâché model of Tucker.

Figure 9. A ticket for Ann.

The children wrote the following in memory of Tucker:

Tucker was a good dog. Tucker had black spots and white on him. We liked his dots. Tucker looked like a Dalmatian. He was soft with thick fur. He was pretty fat. We loved Tucker. He was nice. When we visited Tucker, he licked us. That was his way of saying hello. He was a good dog. We liked playing with him. We could lie down with him. He liked having his tummy rubbed. He liked putting balls in his mouth. He would get excited when he saw us. He would wag his tail. It would tell us that he was happy. Sometimes he would run around with a cow in his mouth when he saw us. He liked to be rubbed on his tummy. Tucker would eat and sniff for food. Tucker had a bone to eat. He liked the dog biscuits we gave him. He was a good dog and he didn't bark. We liked that he would stay still when we petted him. Tucker was a nice dog because Ann wouldn't want to have a mean dog. Tucker was furry and warm. We liked everything about Tucker.

Although the children in David's class learned a lot about a good dog and their own capacities to nurture and care for a sick animal, David also learned-about himself and about the children in his care:

Now we are in a new year at our school, and most of the children who were in my classroom are in kindergarten; and yet they continue to make sense of their world by processing their loss. One child recently said to me, "I like going to kindergarten because everyday I pass the Tucker we made." Another explained that her parents took her to walk through the woods where his ashes were scattered. Only recently, two children-who seemed to forget the events of last spring-asked if they could visit Tucker in Ann's office. We walked to Ann's office and visited with her for a while.

Throughout this experience, I often had doubts about my decision to allow the children to become emotionally attached to Tucker. Although I wasn't surprised that they came to love Tucker, what I had not fully anticipated was their remarkable ability to express empathy for Tucker and Ann. Many children said, "Ann must be very sad." And "I bet Tucker is sad." Their ability to verbally express their thoughts and feelings was displayed in the book written in Tucker's memory. As a teacher, one of the most difficult aspects of risk taking is that curiosity leads you into spaces and places that require you to take a reflective stance. Posing questions and seeking answers through active exploration with children is one way to provide an environment that allows risk taking. Michael took a risk by trusting Ann and Tucker on that cold January morning. I recognized and celebrated Michael's risky experience by taking a risk myself to provide an opportunity for all of the children in my class to learn more about their world.

This risk-rich experience grew out of a serendipitous moment that David recognized and respected as significant-not only for Michael, the child who is blind, but also for the other children in the class. Following their lead, David was able to fashion learning activities suitable to the preschool setting based on initiatives children took. Sometimes, though, teachers decide to take a risk in the absence of a clearly articulated interest of the children; rather, it is the teacher's curiosity-or concern-or knowledge that serves as the catalyst for a risk-rich curriculum that eventually circles back to connect with children's interests and understandings. Ben describes just such a project in his kindergarten class.

Democracy as Making Things Fair

The kindergarten class had been engaged in small group explorations known as "study groups" for most of the school year, and the children were accustomed to having their ideas taken seriously by their teacher (Ben) and the other student teachers in their classroom. When they began to argue about what was fair and how voting might be unfair to people who always lose, Ben-an experienced head teacher-decided that he was ready to take the plunge:

"Smash it! Smash it! Smash it!" chant the majority of my students, while a minority react in horror, hoping to spare the clay bunk bed the class is creating for several beloved puppets (Fig. 10). They plead, "But we worked so hard to make it." Indeed, the children have worked hard on this project, spending over a month drawing design plans, debating structural features, and having multiple sessions building the bed. The impulse to smash began as a reasonable response to cracks that appeared in the clay. During a whole group discussion about this problem, one child suggested taking the bunk apart in order to rebuild it. Deconstruction morphed into destruction, and a mob-like enthusiasm for smashing the bed emerged.

Figure 10. Children constructing clay legs for a bed.

As the children chanted, my mind raced as I considered two seemingly conflicting priorities: protecting the children's work and giving the children meaningful control over their classroom lives. Did the latter include the right for a majority of the group to destroy their own work? Should I risk giving children the option to make a decision I felt was patently wrong? One thing was clear: the current environment was not conducive to making a reasoned decision. I told the class the conversation would be continued.

As I reflected on the morning meeting, I soon realized the bunk bed issue would fit in perfectly with our soon-to-be-launched, culminating, end-of-year classroom study on democracy. It seemed to make sense that the feelings of risk about the bunk bed debate coincided with my feeling about the upcoming curriculum. Studying democracy felt risky. Democracy had become controversial, linked to actions being played out on the other side of the world. While my own reference points about democracy were in Boston rather than Baghdad, and concerned classrooms rather than nation building, I was counseled not to take the high emotions connected with democracy lightly. Democracy was also a pedagogical risk; success was by no means guaranteed. While the issues involved-fairness, rules, decision making, and community-have deep resonances with 5- and 6-year-olds, the word itself is abstract. Until we began our inquiry, the word democracy was completely unfamiliar to most of my students.

Most teachers of young children have accepted the standard mantra of limiting curriculum topics only to those things that provide children with "hands-on" experiences. Why would this experienced teacher decide to pursue a topic of inquiry that is challenging for adults to articulate, much less for children to ponder?

I must admit, the hardness of the subject was one of its appeals. Some of the best and most important teaching occurs when teachers-as individuals or as members of groups-push the boundaries of accepted curriculum. And the topic made sense for our group. This was a class that enjoyed identifying problems, discussing them, and then making up rules to solve them. Yet despite my own interest in democracy, I was initially unsure about proceeding. The thoughtful and enthusiastic responses of several key colleagues (including my director) gave me the conviction to move forward.

How might a teacher pursue a topic of inquiry that is likely to elicit diverse and conflicting responses from parents? In this case, Ben's strategy was to immediately involve the parents in assessing children's learning:

Parents were kept abreast of the curriculum through weekly newsletters, and four weeks into the democracy curriculum, on a Friday after school, 10 parents and I stood around a table covered with kindergartners' pictures about democracy. The images include figures carrying signs reading "Bush" and "Kerry," the U.S.S. Constitution, and a group of people discussing the clay bunk bed. "What strikes me," Yuriko, one of the parents, insightfully observed, "is that the children are attracted to so many different aspects of democracy. My daughter is really interested in the issues about classroom governance and couldn't care less about the historical stories. But it's clear that some kids are really taken by the history." The fact that a majority of the families participated in this discussion is a testimony that the topic of democracy generated much interest among the adults in our school community. The discussion itself, because of comments like Yuriko's, helped draw my attention to aspects of the children's thinking that then moved the curriculum forward.

Eventually, this democracy project evolved into a broad exploration of topics associated with U.S. history-many of which would typically be considered years beyond the reach of 5-year-old children. Topics emerged from both children's interests and suggestions from parents. The children used their new and developing understandings to make critical decisions about their own lives in the classroom:

In the end, the democracy curriculum covered a wide, diverse terrain, from taxation (a subject brought up by a parent serving as a selectman for her local town government) to the American Revolution (Lexington and Concord are just a stone's throw away).

Regarding the bed, three children volunteered to work out a decision-making process, interviewing a number of adults at the school as part of their research. Eventually, a consensus was reached. The group decided to design and build a second bunk bed, and then choose one to save and one to smash. In this process, the children demonstrated their abilities to discuss, work out solutions, take the perspective of others, and advocate for themselves.

This sort of risk-rich classroom project is reminiscent of Carol Seefeldt's (1993) advocacy for classrooms where democracy is lived as a way of life, not as a chapter in a social studies project. Such a commitment is fraught with complexity-many aspects of democracy are surely beyond children's capacities to comprehend. Ben shared more of his thoughts about why he chose to go down this risky path:

Why democracy? I had been thinking about what the capstone curriculum unit should be. Though the previous year's marathon curriculum was very successful, I didn't want to repeat it, as it might feel stale. Based on the children's interests, friendship was a leading candidate, but that just didn't inspire me. I had been thinking a lot about democracy, and then, in the midst of a very heated discussion the children were having about whether there should be a rule banning candy from lunches, it hit me that this was a group that could certainly study democracy.

Of course how to frame this, explain it to children, how much information and definition to give them and how much to let them explore-these were all issues. The exploration part was a challenge to figure out since democracy wasn't something you could go watch or touch or smell.

What Ben learned, however, is that exploring a concept such as democracy is not as difficult as it seems, not when children's ideas are elicited, their disagreements are aired, and their understandings and agreements negotiated and documented. Ben notes the value of participating in these experiences-not only for the children, but for him:

For this middle-aged teacher, who at times can fall victim to cynicism, seeing the children in action helped restore some of my faith in the possibilities of democracy. For all involved, children and adults alike, the curriculum, to borrow a phrase from Saul Bellow (1982), helped open the universe up a little more.

Moving from Playing It Safe to Being Collaboratively Courageous

In this article, we have described teachers (ourselves and others) making choices on behalf of children and working in the guise of curriculum that reflects beliefs about what seems best, right, necessary, essential. What is not always acknowledged is that each of these decisions about what to do entails implicit if not explicit decisions about what not to do. Effective teaching in this light has recently been described as akin to jazz or improvisation, such that the teacher's responses to children link with what they have proffered and, in the next moment, take them to a place not yet fully defined but ripe with possibilities (Sawyer, 2004). And yet scholars have documented the general aversion to such ambiguity; more recent research of classroom dynamics attests to the anxiety that teachers often feel when they are unable to predict or control the outcome of their interactions with children. That teachers would be averse to purposefully adding risk taking to their professional repertoire is thus not surprising. And yet, when we consider the alternative possibilities consciously eliminated or unconsciously precluded as teachers go about their daily planning and interactions with children, we are left with an image of teaching that is unavoidably risk filled.

We do not propose to redefine the parameters of safety and risk as applied to early childhood education, nor do we mean to suggest that teachers disregard concern for children's well-being. Rather, our aim has been twofold: (1) to suggest that the topic of risk is more complex and culturally situated than is typically understood, and (2) to highlight the potentials of an explicitly risk-rich curriculum. Our stories—about a dog and a project on democracy—have in common a willingness to embrace unknown territories, new ideas, and new relationships. In sharing stories of our own experiences with risk taking, we argue in favor of being less fearful and more open to an early childhood curriculum characterized by purposeful and collaborative risk taking. Such a "risk-rich" early childhood curriculum

- acknowledges children as capable and desirous of testing their developing skills and understandings of and in the world,

- invites parents into collaborative relations that inform decision making about what and how children can learn, and

- encourages teachers to trust themselves and their children to learn together while exploring meaning making in the real world they inhabit.

Such an approach to the early childhood curriculum requires more than courage to "move out and beyond" the status quo (Gitlin, 2005). It also requires curiosity and imagination as well as faith in the collective intelligence of teachers, children, and families. Such a curriculum has the potential to not only benefit children—it also reminds adults of the purposes of an early childhood education in a democratic society. This orientation to the care and education of young children is also consistent with an image of teaching as a means to expand "the space of the possible" (Davis, 2004). Given the multiple challenges facing children, families, and teachers in an increasingly unpredictable global society, it may well be that the best way to keep children safe is to be willing, as adults, to take more risks on their behalf. Such a public embrace of negotiated risk taking makes explicit the moral dimensions of teaching-and invites parents and community members to join in the conversation. We can think of no other more worthy goal to which we might direct our efforts.

References

Bellow, Saul. (1982). The dean's december. New York: Penguin.

Bransford, John D.; Brown, Ann L.; & Cocking, Rodney R. (Eds.). (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school (pp. xiv-xv). Washington, DC: National Academy Press. ED 436 276.

Davis, Brent. (2004). Inventions of teaching: A genealogy. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dewey, John. (1926). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: Macmillan.

Fuller, Bruce; Eggers-Pierola, Costanza; Holloway, Susan; Liang, Xiaoyan; & Rambaud, Marylee F. (1996). Rich culture, poor markets: Why do Latino parents forgo preschooling? Teachers College Record, 97(3), 400-418. EJ 525 350.

Gitlin, Andrew. (2005). Inquiry, imagination, and the search for a deep politic. Educational Researcher, 34(3), 15-24.

Hayes, Noirin. (2005, September). Including young children in early childhood education. Keynote address presented at the15th Annual Conference on Quality in Early Childhood Education: Young Children as Citizens, European Early Childhood Education Research Association, Dublin, Ireland.

Lewis, Catherine C. (1995). Educating hearts and minds: Reflections on Japanese preschool and elementary education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ED 382 383.

New, Rebecca S. (1999). What should children learn? Making choices and taking chances. Early Childhood Research and Practice [Online], 1(2). Available: http://ecrp.illinois.edu/v1n2/new.html [2005, October 11]. ED 435 501.

New, Rebecca, & Akslen, Aase. (2005, September). Cultural differences in the place of values in early childhood education. Paper presented at the 15th Annual Conference on Quality in Early Childhood Education: Young Children as Citizens, European Early Childhood Education Research Association, Dublin, Ireland.

Paley, Vivian. (1992). You can't say you can't play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sawyer, R. Keith. (2004). Improvised lessons: Collaborative discussion in the constructivist classroom. Teaching Education, 15(2), 189-201.

Seefeldt, Carol. (1993). Social studies: Learning for freedom. Young Children, 48(3), 4-9. EJ 460 157.

Tobin, Joseph J. (2005). Quality in early childhood education: An anthropologist's perspective. Early Education and Development, 16(4), 421-436.

Tobin, Joseph J.; Wu, David Y. H.; & Davidson, Dana H. (1989). Preschool in three cultures: Japan, China, and the United States. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Author Information

Rebecca New is associate professor of child development at the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Development at Tufts University. A classroom teacher for nine years, she has spent the past three decades working in the fields of early childhood teacher education and cultural psychology. Her scholarship focuses on the cultural bases of early care and education, and a bulk of her research has been conducted in Italy. She is currently completing a book-length manuscript on a collaborative study on home-school relations in the cities of Reggio Emilia, Milan, Trento, Parma, and San Miniato. She is also conducting a pilot study on parent and teacher conceptions of school readiness in a Head Start program for children of Chinese immigrant parents living in Chinatown, Boston. Her primary interests are in the interface between cultural values, children's development, and adult relations within pluralistic democratic societies.

Rebecca S. New

Tufts University

Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Development

105 College Ave.

Medford, MA 02155

Telephone: 617-627-4129

Fax: 617-627-3503

Email: becky.new@tufts.edu

Ben Mardell has worked in early childhood education for over 20 years, mostly as a classroom teacher. He holds a master's degree from Wheelock College and a doctorate from the Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Development at Tufts University. Ben is the author of From Basketball to the Beatles: In Search of Compelling Early Childhood Curriculum and Growing Up in Child Care: A Case for Quality Early Education. From 1999 to 2001, he worked at Harvard Project Zero, collaborating on the publications Making Learning Visible: Children as Individual and Group Learners and Making Teaching Visible: Documentation as Professional Development. Ben is currently the kindergarten teacher and research coordinator at the Eliot-Pearson Children's School in Medford, Massachusetts.

David Robinson has worked as a preschool teacher for 15 years. He has a B.S. in early childhood education from Boston University and a master's from the University of Pittsburgh. His recent projects include finding creative ways to integrate clay into the classroom curriculum and exploring documentation as it helps teachers understand children's classroom experiences. David has presented workshops at NAEYC about centerwide curriculum projects and anti-bias curriculum. He currently teaches preschool at the Eliot-Pearson Children's School at Tufts University.