Volume 6 Number 2

©The Author(s) 2004

Head Start Families Sharing Literature

Abstract

The purpose of this research was to ascertain the types of books read by Head Start families to their children, conditions for reading aloud at home, perceived benefits of reading aloud, and children's responses to books. Data were collected from parent interviews and reading logs. Participants included 14 children and families from four Head Start classrooms located in two states. Researchers conducted content analysis and frequency counts of the data. Researchers used qualitative research methods to explore the ways books were used at home and children's responses to reading aloud. Systematic review of both parent reading logs and parent interviews led to common patterns and frequencies of responses. Findings indicate that Head Start families read to their children mostly in the bedroom at night. Mothers were the primary readers, sharing mainly books that were not challenging in terms of language and concepts. Children responded to the books by relating them to their own experiences, noticing details in pictures, asking questions, labeling, reading emergently, and enacting stories. Recommendations include encouraging families to read many times during the day, supporting a variety of responses, and accessing high-quality children's literature.

Introduction

Each child follows a distinctive path to literacy, created by unique personal, family, social, and cultural factors. Literacy practices vary from family to family, with children acquiring internal understandings of and dispositions toward spoken and written language. The foundations of literacy begin long before formal instruction, as preschoolers observe adults and older children interacting with oral language and print. It is critical for early childhood educators to learn about children's past literacy experiences and ongoing practices in order to understand the attitudes and abilities they bring to school or child care (Martello, 2002; Taylor, 1997).

Research over the past three decades has illuminated the importance of a strong oral language foundation (Hart & Risley, 1995; Pellegrini, Galda, Jones, & Perlmutter, 1995; Rowe, 1998; Rush, 1999; Valdez-Menchaca & Whitehurst, 1992), the efficacy of families reading aloud to children from an early age (Morrow, 1995; Schieffelin & Cochran-Smith, 1984), and the value of books in the home (Aulls & Sollars, 2003; Cochran-Smith, 1984; Neuman, 1996; Whitehurst, Arnold, Epstein, Angell, Smith, & Fischel, 1994) for later achievement. Children learn new vocabulary, gain important concepts, and develop a sense of story from hearing books read at home during the years before school (Clay, 1991; Green, Lilly, & Barrett, 2002; Harste, Woodward, & Burke, 1984).

Figure 1. A mother reads to her daughter.

The achievement gap between children from low-income families and children from middle-class families has been documented over several decades (Baker, Sonnenschein, Serpell, Scher, Fernandez-Fein, Munsterman, Hill, Goddard-Truitt, & Danseco, 1996). Recent evidence reveals the significance of the years before school as a critical time for developing a strong foundation in language, awareness of print, and development of story concepts (Hart & Risley, 1995; Jordan, Snow, & Porche, 2000; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998). An understanding of the home literacy environment of low-income children may assist teachers as they plan emergent literacy experiences for children from diverse cultures and varying income levels. Although there have been many studies on the value of reading aloud to young children, few have focused specifically on the family reading habits of low-income or Head Start families.

Nespeca (1995) interviewed nine urban mothers of Head Start children (four African American, three European American, and two Hispanic) regarding their literacy practices. The open-ended questions explored mothers as role models for reading, values placed on reading, personal experiences with literacy, parental involvement with children's early reading and writing explorations, and the role of the library. Mothers in this study reported very little or no reading-aloud experiences in their own childhoods. Two mothers commented that they had become avid readers as adults, and eight of the nine mothers read to their children and discussed books while reading. In one family, the 7-year-old read to the younger child. Seven of the mothers mentioned reasons why reading was important, such as learning about the world, using one's imagination, and as a pastime. In addition to reading aloud, many parents introduced some academic skills, including letter recognition and counting, sometimes using flash cards and workbooks. The time spent on literacy endeavors (e.g., reading aloud, acting out roles of story characters, practicing ABCs from flash cards, playing games, and memorizing prayers) varied among the families in the study. Mothers also differed in the times they began reading to their children: three reported reading to their children during infancy, two started when the baby was about a year old, two started when their children reached 2 years, and one did not begin until her child was in Head Start. The time spent on literacy endeavors and the types of activities varied among these families.

In a study of 39 Head Start children and their families, Rush (1999) examined the children's levels of early literacy skills and the degree to which these skills were related to caregiver-child shared reading and language interactions. The early literacy skills assessed in this study were letter-naming fluency, onset recognition fluency, and phoneme blending. Caregiver factors were measured using selected questions from a standardized family reading survey along with one-hour structured observations. Pearson product-moment correlations indicated three types of caregiver interactions that contributed to children's early literacy skills: structured play following the child's lead, language characteristics of the caregivers, and the amount of shared book reading and connected literacy activities.

Parents' thoughts about their second-grade children's reading habits at home and the importance of reading were examined by Anderson (2000). The 95 African American children in the study attended an inner-city school where the mean family income was $10,000-$15,000 per year. The students were given the Gates-MacGinitie Reading Test, with a resulting average grade equivalent of 1.2 for vocabulary and 1.5 for comprehension at the beginning of second grade. Highlights from the parent interviews included the following findings: only 16% of parents read to their children daily, 58% read in front of their children daily, 75% asked questions when reading to their children, and 95% felt that reading was very important. During a 6-week intervention, 100% of students read to their parents in week 1, but in week 2, only one-sixth of the children acquired library cards and checked out books. Participation was so low on subsequent literacy activities (reading recipes, and bringing library books to school) that the researcher eliminated the last two weeks of the intervention.

A study comparing the early literacy skills of 3- to 5-year-olds in 1993 with a group of 3- to 5-year-olds in 1999 showed that children from middle-class families had higher-level skills in 1999 than did their 1993 counterparts; however, children from poorer families or families where English was not spoken by the mother were at about the same level as their 1993 counterparts (Nord, Lennon, Liu, & Chandler, 2000).

In a study of prekindergarten children from low- and middle-income African American and European American families in Baltimore, Baker and colleagues (1996) asked parents to keep a diary of their children's activities for one week. Researchers followed up with interview questions relating to literacy-enhancing activities. The results of the study showed that children in all of the families participated in events that were connected to literacy, such as book reading, singing, viewing television, and conversing during mealtime. Parents seemed to be guided by one or more of the following views of literacy: literacy as a pleasurable activity, literacy as a set of skills to be learned in a planned way, and literacy as an essential part of daily life. The researchers found that in middle-income families, there were many activities in which literacy was seen as a source of pleasure or entertainment, such as children pretending to read to each other. The low-income families reported fewer activities with print. The print engagements that did occur involved an emphasis on skills such as learning alphabet letters, spelling names, and flash-card practices. Many low-income families also engaged in literacy for pleasure, including reading aloud with excitement and expression. ".[M]iddle income families tend to adopt a more playful approach in preparing their children for literacy than low-income families" (Baker et al., 1996, p. 71). The children whose parents stressed literacy as a source of entertainment were stronger on print knowledge (e.g., letter identification, concepts about print, purposes of written materials) and story comprehension than children whose families emphasized a more skill-based approach to literacy learning. Greater differences were seen in this study based on income than were seen based on ethnicity.

Many families with young children have received the message that reading aloud and owning books are important for later achievement. Not all families, however, have equal access to high-quality literature for their children. Research by Neuman, Celano, Greco, and Shue (2001) revealed that although families with incomes below $30,000 purchase 33% of all juvenile trade books, those earning $30,000-$49,999 purchase 25%, those earning $50,000-$74,999 purchase 20%, and families with incomes above $75,000 purchase 22%. A recent government study found that 63% of White Americans reported having more than 50 books in their homes, but only about 25% of families from other ethnic backgrounds have that many (Bracey, 2000). There are more places to purchase children's books in high-income neighborhoods (bookstores, grocery stores, children's stores, and discount stores) compared with low-income neighborhoods (Duke, 2000; Haycock, 2003). Libraries in high-income neighborhoods provide more books per child than those in low-income areas and are open longer hours (Duke, 2000). During times when the job market and economy are not thriving, schools and libraries have less money for book purchases, limiting accessibility for low-income families and widening the gap between middle-class and poor children.

Access to books has been associated with higher levels of literacy (Krashen, 1993). Extreme differences in access to books were found within families in three communities in the Los Angeles area (Smith, Constantino, & Krashen, 1997). The researchers visited children and families in Beverly Hills, Compton, and Watts, counting books in each home. The wealthy children had a mean of 199.2 books, working-class children had 2.67 books, and those in poverty had an average of .4 books per home. The classroom collections for these three geographic areas were similarly disparate, as were the public library collections.

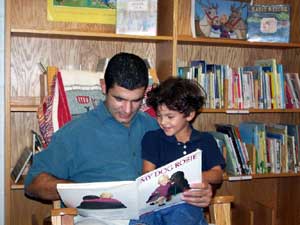

Figure 2. A grandmother reads to her grandson.

Green, Lilly, and Barrett (2002) investigated the ways in which families share books with young children and children's responses to books within the home setting. They asked parents of 12 children (predominantly middle-class and European American) to keep a journal of the books they read and the youngsters' responses to literature during a 3-month period. The children ranged in age from 14 months to 5 years. Parents recorded between 5 and 29 anecdotes about their children's comments and activities related to books. The researchers also interviewed families on two occasions regarding reading routines, favorite books, and the benefits that they perceived from reading to their children.

Data from reading logs and parent interviews indicated that families shared books in the following ways: conversations during reading, activities during reading (e.g., counting objects in books, making sounds of animals), and comments and activities at other times (parents listening as children retell stories from pictures). Children in this study responded to books primarily in five ways: (1) literary language (using the vocabulary or syntax of a book), (2) concept acquisition (developing concepts or acquiring skills from books), (3) book-related dramatic play (enacting stories or illustrations), (4) affective associations (developing understanding of emotions and relationships), and (5) book-related experiences (arts, crafts, cooking, outings). The study described in this article is a replication and extension of this research, focusing on culturally diverse, low-income Head Start families.

Methodology

Background

Qualitative methods of inquiry, data collection, and data analysis were used in this study. Questions posed in an earlier study of book sharing and young children's responses within the home setting (Green, Lilly, & Barrett, 2002) led us to the guiding questions. We gained access to the research subjects via Head Start teachers and social workers who facilitated communication with families. The two data sources were reading logs and interview data on parent perceptions of the benefits of reading aloud. These data sources provided insights into types of books read, location of reading, people who read to the children, time of day reading occurred, and responses to books.

Participants and Setting

The participants in this study included 14 children and their families from four Head Start centers, two in North Carolina and two in Florida. The children ranged in age from 3 years to 4 years 11 months, with a mean age of 4 years 2 months and a median age of 4 years 4 months. Equal numbers of boys and girls participated.

Of the seven children from a small university town in North Carolina, two (one African American and one Hispanic American) attended a free-standing Head Start center located in an old home. The other five children attended Head Start in a rural elementary school near the Tennessee border. Both Head Start programs followed a public school schedule. Three of the families from the rural program lived in mobile homes, and two lived in single-family houses. Six of the children had one sibling, and one had four.

The seven children in the Florida study attended Head Start classrooms in two elementary schools where they followed a public school schedule and were part of the ongoing events within the school. Five of the children in the Florida group were African American, and two were European American. One child, who was visually impaired and learning Braille, received services from a special needs coordinator, but the child participated fully in the regular Head Start program. The families lived in apartments and single-family homes in an urban area. Three of the families were headed by single mothers. In the four remaining families, children lived with both parents. Three of the children had one sibling, one child was an only child, and one child had three siblings.

Procedures

Four questions guided this study:

- What are the conditions for reading aloud at home: time, location, and reader?

- What types of books do Head Start families read at home with their children?

- What were the perceived benefits of reading aloud for these families?

- How do Head Start children respond to reading aloud within the home?

In each location, a parent meeting was held to introduce the study and explain procedures that the researchers would follow. North Carolina participants were told about the study during a regularly scheduled Head Start parent workshop. At one center, the researcher conducted a workshop on positive discipline, followed by a description of the project. At the second center, graduate students presented a workshop for families and child care providers on the same topic, with the researcher explaining the study to parents at the end of the meeting. In the Florida study, the researcher met with families to explain the study after a potluck dinner held in the Head Start classroom.

Families in both states who expressed interest in the study were given a letter explaining the procedure, a consent form, and a blank reading log. Interview times were either arranged at the meetings or in follow-up phone calls. Several families in each location agreed to participate but did not collect the data or follow through with appointments. They were dropped from the study.

Interviews took place before and after school at the Head Start centers in Florida, with the exception of one mother, a family day care provider, who was interviewed in her home. In North Carolina, the mothers from the school-based center were all interviewed in their homes. The mother of one of the children in the free-standing center taught Spanish at a local elementary school and was interviewed at the school. The second mother was interviewed in the Head Start center where she worked as a cook. No fathers were present for the interviews. During the first interview (Figure 3), families were asked questions about their own reading experiences as children, their reading practices with their own children, and their children's responses to books. The researchers reviewed procedures for the study outlined in the initial letter and gave the family the first gift book at the conclusion of the interview.

- What types of reading experiences do you remember from your own childhood?

- What do you remember about being read to?

- What books do you remember?

- Who read to you?

- What do you remember about reading books to yourself?

- Tell me about the ways you share books with your child.

- What are some of your child’s favorite books? Why do you think he/she finds them so appealing?

- What have you learned about reading aloud from your child?

Figure 3. First parent interview.

Families were encouraged to follow typical reading routines and to make notes of titles of books read, time of day reading occurred, names of readers, location of reading, and the child's responses to the books. They were provided with reading logs containing spaces for 15 entries, copied on colored paper.

The study lasted 3 to 5 weeks, depending on families' completion of the reading logs. Calls to the home were made at least once during the study to check on progress and to set a convenient time for the second interview. Second interviews (Figure 4) were conducted by telephone or in the home, with reading logs either being returned to the Head Start Center or collected during home interviews. An additional gift book was provided at the time of the second interview. At one center in the Florida study, a culminating meeting was organized by the classroom teacher and researcher to thank families for their participation and to share highlights about the findings and benefits of reading aloud. Thank-you letters were sent to all participating families.

- How do books help your child understand new experiences and things in the natural world?

- What are his/her favorite books now?

- What is your current reading routine?

- Do you ever read about places you visit or different types of families?

- In what ways do you think reading helps your child?

Figure 4. Second parent interview.

In analyzing the results of the study, the researchers examined two primary sources of data: reading logs and parent interviews. Notes from parent interviews were transcribed as soon as possible after the visit and were later arranged by question for ease in analysis. Systematic data analysis was employed in order to make sense out of the parent notes, reading logs, and extensive interview data that were collected. The guiding questions gave focus to the analysis as researchers sorted and categorized the data to each of the questions. From these questions, themes and patterns emerged, leading to analysis of the content and connections to each of the questions (Bogdan & Biklen, 1982; Sherman & Webb, 1997).

Reading log records were entered into the Microsoft Excel database program and were organized by child's name, time of day, reader, title of book, location of reading, child's comments, and child's activities. The researchers worked independently to discern patterns in the data collected on children's responses and activities. Next, researchers coded and categorized data independently, then together, to look for emergent themes; then they made frequency counts of the time of day, persons who read aloud, and location where reading occurred. After content analysis, they also conducted frequency counts on types of books read, children's comments, and children's activities.

Results

Results of the study were based on the researchers' inquiry into the conditions under which reading occurred (time, location, and reader), types of books read aloud, perceived benefits of reading aloud, and children's responses to literature.

What Were the Conditions for Reading Aloud at Home?

When Did Families Read Aloud? The majority of book-reading episodes (67%) occurred at bedtime, with early evening being the second most popular time (27%). Few families reported reading in the morning (5%), afternoon (3%), or noontime (3%) (Table 1). Several mothers commented that they read stories to their children between bath and bedtime, and they put their children to bed at 8:00. One mother added that their family read a lot on Friday nights because the children needed to unwind; another mentioned reading books to her two children after school.

| Time of Day |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Bedtime |

|

|

| Early evening |

|

|

| Afternoon |

|

|

| Noon |

|

|

| Morning |

|

|

According to a mother of five, it was not always possible to read aloud because of their family size and busy schedule (both parents were ministers). In families with more than one child, parents often read to all of the children at the same time.

Where Did Families Read? The location for reading aloud was fairly consistent across the 14 families. The most frequent setting was the child's bedroom (42%), followed by the living room (31%). Other places families reported reading were outside (8%), parents' bedroom (6%), grandmother's house (5%), kitchen table (4%), and floor (4%) (Table 2).

| Location | Number of Responses | Percentage of Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Child's bedroom | 72 | 42% |

| Living room | 52 | 31% |

| Outside | 13 | 8.0% |

| Parents' bedroom | 11 | 6.0% |

| Grandmother's house | 9 | 5.0% |

| Kitchen table | 7 | 4.0% |

| Floor | 6 | 4.0% |

Who Read to the Children? Mothers were by far the most frequent readers. Based on the reading-log data, 76% of the time mothers read with their youngsters. Siblings read 14% of the time, and fathers and grandmothers each read 5% of the time (Table 3). The mothers in this study seemed to spend more time at home with their children than did the fathers. With one exception, the mothers were present for all of the interviews.

| Reader | Number of Responses | Percentage of Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Mother | 143 | 76% |

| Siblings | 27 | 14% |

| Father | 10 | 5.0% |

| Grandmother | 9 | 5.0% |

What Types of Books Did Families Read?

The data analysis revealed that the families in this study read several types of literature, which the researchers classified as noteworthy literature, concept books, folktales, religious books, and other. Noteworthy literature, as defined by Beck and McKeown (2001), comprises texts that are effective for developing language and comprehension. These books contain concepts that challenge children to wrestle with ideas and actively construct meaning from the text. They are written by skilled authors, whose work withstands critical analysis of experts in the field of children's literature (Darigan, Tunnell, & Jacobs, 2002). High-quality books for young children also have exemplary illustrations by well-known artists, rhythmical language, straightforward narrative, strong characters, positive values, and new information about the world. The elements of style, language, plot, character, setting, and theme are considered exemplary. Many high-quality books provide a positive reflection of the diversity within the United States and the world. The themes addressed in high-quality literature for young children expand children's everyday experiences and go beyond their daily routines (Cochran-Smith, 1984), thus helping children develop new concepts and related vocabulary (Feitelson, Kita, & Goldstein, 1986).

The following two examples demonstrate the difference between language in pop culture books and noteworthy books:

Pop Culture Book:

"Her wicked stepmother and spoiled stepsisters made Cinderella do all the chores, day and night" (Findlay, 2004, unpaged).Noteworthy Book:

"The girl had to do all the unpleasant tasks about the house, scrubbing and sweeping and keeping her stepsisters' beautiful rooms clean and neat, while she herself slept on a wretched straw mattress in a little attic" (Perrault, 1999, unpaged).Pop Culture Book:

"He swam off to explore and he found Tubb and Sploshy in a beautiful underwater palace" (Silverhardt, 2004, unpaged).Noteworthy Book:

"Only Swimmy escaped. He swam away in the deep wet world. He was scared, lonely, and very sad" (Lionni, 1963, unpaged).

Noteworthy books read by study participants included The Little Engine that Could (Piper, 1961), Where the Wild Things Are (Sendak, 1963), Buenas Noches, Luna (Good Night, Moon) (Brown, 1990), If You Give a Mouse a Cookie (Numeroff, 1985), No, David! (Shannon, 1999), and Rosie's Walk (Hutchins, 1998). Most of these were gift books provided by the researchers.

We classified 29% of the books read by study participants as noteworthy or high-quality literature. In addition, 10% of the books read were concept books (e.g., books about shapes, colors, letters, or numbers), 6.5% were folktales (e.g., Little Red Riding Hood, The Three Pigs), and 6.5% focused on religious themes (e.g., prayer books and Biblical stories). A large number (48%) of books read by families in this study were classified as "other." These books were not challenging in terms of language or concepts. Many of the titles were based on television characters or toys (e.g., Disney characters, Rugrats, and Barbie). These appeared to be books purchased at grocery or discount stores (Table 4).

| Type of Book | Number of Books | Percentage of Books |

|---|---|---|

| Noteworthy literature | 54 | 29.0% |

| Folktales | 12 | 6.5% |

| Concept books | 19 | 10.0% |

| Religious books | 12 | 6.5% |

| Other | 88 | 48.0% |

Four mothers said that they read different types of books (genres) and did activities with some books, such as gluing leaves after reading a book about trees or playing hide and seek after reading a book on that topic. During the time of the study, there were only two reported instances of families reading poetry or Mother Goose books.

Several mothers mentioned that they read multicultural books. The mother from Puerto Rico said that her daughter liked books with little girls who had skin that looked like her own. One African American mother chose Peter's Chair (Keats, 1967) as her gift book because it was about "a little black boy." A rural Appalachian mom said she used books to introduce her child to "all kinds of families, like families without dads."

What Were the Perceived Benefits of Reading Aloud?

During the second interview, mothers discussed their beliefs about the advantages that reading aloud gave their children. Because all of the families in the study reported reading to their children, it is believed that they viewed it as a worthwhile activity. When asked, "How has reading aloud benefited your child?" three mothers reported each of the following: learning letters and sounds, expanding vocabulary, and pretending to read. Other mothers reported that their children developed longer attention spans, greater imagination, and the ability to predict upcoming events in a story. One mother said that her child listened to books for long periods of time and wanted to hear books read again and again. Another mother said that her daughter hears different words and asks her mother how to spell them. At 4, the child knew some beginning sounds and wanted her mother to spell the whole word.

How Did Children Respond to Reading Aloud within the Home?

Thirteen types of responses emerged from the data in the reading logs and interviews (Table 5 and Table 6). We will discuss the six most prevalent response categories: (1) asking questions, (2) labeling or naming, (3) noticing details in pictures, (4) relating books to personal experiences, (5) emergent reading, and (6) story enactment (see Figure 3).

| Children's Book Responses | Number of Responses | Percentage of Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Relating books to personal experiences | 39 | 16% |

| Noticing details in pictures | 29 | 12% |

| Asking questions | 26 | 11% |

| Labeling, naming, or counting | 25 | 11% |

| Story retelling | 23 | 9.5% |

| Story enactment | 22 | 9% |

| Drawing conclusions about pictures or story | 18 | 7.5% |

| Requesting object or action from book | 16 | 6.5% |

| Attention to print | 16 | 6.5% |

| Morals and values | 10 | 4.5% |

| Arts and crafts | 8 | 3.0% |

| Predictions | 5 | 2.0% |

| Singing | 3 | 1.0% |

| Responses | Definitions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Asking questions | All types of queries related to the storyline, pictures, or vocabulary. | "Mommy, can we go on a train?" "Can a dog really sail a boat?" "What is a difference?" Timmy wanted to know what kind of animal a seal is. |

| Labeling or naming | Pointing to and naming pictures. Counting. Naming colors. | Mary counted things on each page of a concept book, named the colors, and matched things together. While reading Buenas Noches, Luna (Good Night, Moon) (Brown, 1990), Juanita said the words in Spanish, then pointed to each picture and said the name in English. |

| Noticing details in pictures | Distinguishing specific aspects of the illustrations, such as ways characters are related, hidden objects, and characteristics of the setting. | While listening to a story about cars, Clay said, "That’s a high truck. Drove his car right into the water and then on the beach." While reading Froggy Goes to Bed (London, 2002), Ellen remarked, "Oops, he accidentally spilled it there and there. He closed the door real nice." |

| Relating book to personal experience | Child makes a connection between the book and something she or he has done in the past. May also connect to something in the environment or outer world. | After hearing a book about fishing, Jenny observed, "Granddaddy likes to go fishing." Helen told her mother which foot was her left foot and which was her right. She said that they didn’t have front and back legs like some of the people in the book had. She had just heard The Foot Book (Seuss, 1988). |

| Emergent reading | Retelling all, or part of, a story based on memory or language patterns. | Darren’s mother wrote, "Darren really understood this book, because he repeated every word that I read in the book." Following her mother’s reading of The Sailor Dog (Brown, 2000), Martha and her mother "looked at the pictures, and she read her own version of the book." |

Relating Books to Personal Experiences. Many children made connections between books and things they had done in the past or experienced in the environment or the outer world. Sixteen percent of the responses fell into this category. Parents sometimes facilitated these connections by extending the child's comments or engaging the child in a discussion about a related topic. When Melissa's mother read a book about a father cutting down a tree, the 3-year-old observed, "We have lots of trees. I like to play in the leaves." On another occasion, after listening to My Dad, the Magnificent (Parker, 1990), Melissa said, "I love my daddy. Karen don't have a daddy. Daddy always tucks me in when he can, but he don't know how to say prayers." Jenny remarked on her own ability to tie her shoes when her grandmother read Froggy Gets Dressed (London, 1995).

After hearing a story called Tight Times (Hazen, 1983), Blair mentioned that he didn't like lima beans either. Jennifer said, "My favorite color is red. I know my colors," after hearing a concept book on this topic. She then named colors of items in her bedroom. When Helen saw a worm in the book that she was reading, she reminded her mother of a worm that they had seen and showed her how it moved. Relating text and pictures to personal experiences extends children's comprehension and makes the story more meaningful (Wolf & Heath, 1992).

Noticing Details in Pictures. When children noticed details in pictures, they distinguished specific aspects of the illustrations, such as noting the way book characters were related, finding hidden objects, or mentioning characteristics of the setting. Early childhood teachers and parents have often observed that children discern features in pictures that adults overlook. Several of the children demonstrated this type of visual literacy. Eleven of the 14 children distinguished details in pictures during at least one read-aloud session. This category was the second most common category; it included 12% of the responses from the reading logs.

As he heard a book about the seashore, Curt, an observant 3-year-old, said, "Look at that big crab. He'll pinch you if you hurt him" and "That's what sand fleas look like." Referring to Leo the Late Bloomer (Kraus, 1971), he said, "Leo is in the hole. His dad is catching the rabbit." When his mother read him The Selfish Crocodile (Charles, 1999), Denver said, "Look at their eyes. They're scared," and "He's picking his teeth with a stick." Blair noticed that a pumpkin had "two eyes, a nose, and a mouth." In response to The Rugrats Versus the Monkeys (David, 1998), Curt commented, "They built a Pterodactyl, just like we are going to."

Asking Questions. For the purposes of this study, "asking questions" was defined as all types of queries related to the story line, pictures, and vocabulary. Children's natural curiosity appeared to be stimulated by the illustrations and words in the picture books that their families read to them. Eleven of the 14 children asked questions at some time during the course of the study, and 11% of the responses were in the form of questions.

When Curt's mother read Harold and the Purple Crayon (Johnson, 1983), Curt looked at the picture of Harold and the moon and asked, "How can the moon go with him?" He quickly proposed his own answer: "Maybe it follows you when you walk." His other questions were more specific, such as, "What's that?" when pointing to something in an illustration, or "What did that goat say?"

Jennifer asked many questions relating her own experiences and desires to the events in books. "Mommy, can we get a kitten?" was asked after hearing a story about a cat. After reading The Velveteen Rabbit (Williams, 1983), she requested a rabbit, and she wanted to go on a train ride after hearing a story about a train.

A few children asked questions to help them understand a story better. Timothy wanted to know what a seal was, and Helen asked which plant (in the picture) was a squash. Clarification questions were not common among the children of this group.

Labeling, Naming, and Counting. Children often pointed to objects in pictures and named them, identified colors, or counted items in picture books. For example, when reading a book about monkeys, Helen counted the animals on each page. Mariana labeled items in Spanish and English when her mother read her Buenas Noches, Luna (Brown, 1990). Along with his mother, Blair made sounds for each animal in a concept book. Denver pointed to the picture in Peter's Chair (Keats, 1967) where the father and son are painting furniture for the new baby's room and noted, "Pink, pink, pink-everything is pink."

Emergent Reading. In the family interviews, five mothers told us that their children often retold stories based on illustrations, memory, or language of the story. Reading-log data showed that such emergent literacy responses constituted 9.5% of the responses in this study.

Mariana's mother reported that her daughter predicted words in Madeline (Bemelmans, 1939) based on the rhyming scheme. Janna's mother mentioned that her 4-year-old had retold If You Give a Pig a Pancake (Numeroff, 1998) to her younger sister three times. "She loves to be able to look at the pictures and tell the story to herself," the mother wrote. On another occasion, Janna read nursery rhymes along with her mother from I Love Nursery Rhymes (Barney) (Golden Books, 1997).

On two occasions during the study, Melissa reached for a book after her mother had read it and told the story back to her. Once she said, "Let me read it to you." This 3-year-old enjoyed retelling stories to herself or family members.

A few examples of emergent reading included a focus on print. Shanda's mother encouraged her daughter's questions about letters and sounds. "She asked questions as to why this letter comes first or last," her mother wrote. She also reported that they sang the ABC song after reading a Sesame Street alphabet book. "We sang the ABCs. I had her repeat them after me. I helped her write them down, and we picked out the letters that spelled her name. She really enjoyed it. We also talked about the shapes of the letters."

Ella's mother reported: "Ella is so familiar with the book that she read most of it along with me." She also pointed out her name in the gift book they were reading. "See, this says Ella. My teacher gave this to me." On another occasion, Ella pointed to and named the letters in an alphabet book.

Summary and Discussion

Read-aloud times provided warm, nurturing experiences for the Head Start children and families in this study. Parents valued the language and cognitive benefits of reading and shared books with their children regularly, if not every day. Almost all families read to their children at night, but much less frequently during the day. One mother commented that her children were tired after their bedtime stories and did not talk about books or engage in response activities because of the late hour. Teachers might recommend that, in addition to bedtime, families read to their children at earlier times during the day when children and adults would be more likely to actively respond to books.

In both of the research sites, families encouraged various forms of response, the most frequent of which were (1) asking questions, (2) labeling and naming, (3) noticing details in pictures and text, (4) relating books to personal experiences, and (5) emergent reading behaviors. Families might be encouraged to expand their children's responses to include more enactment of stories, predictions, and drawing conclusions that could enhance comprehension and higher-level thinking.

Reading aloud, mediated by adults, has been shown to have a positive influence on children's ability to comprehend literature. Specifically, the benefits extend to the following areas (Feitelson, Kita, & Goldstein, 1986):

- Reading aloud enriches the child's knowledge base. New terminology and themes outside the child's immediate experiences are often addressed.

- Reading aloud introduces the child to grammatical forms and ways of using language that are not commonly found in oral language.

- Reading aloud helps the child become familiar with the structure of stories.

- Reading aloud helps the child become familiar with literary devices, such as metaphor and simile.

- Reading aloud extends the young child's attention span.

When basic measures of early literacy development (i.e., letter recognition and formation and book handling) are administered at a child's entry into school, they are strong predictors of later academic achievement. Other good predictors of school success are knowledge of traditional nursery rhymes and having favorite books (MacLean, Bryant, & Bradley, 1987). The variability we see in children's abilities upon school entrance is most often caused by the home environment and experience families have provided during the early years. The home literacy environment continues to have a strong influence on children's academic success (Hannon, 1998).

Figure 5. A father reads to his son.

Implications and Directions for Future Research

This exploratory study provides a glimpse into the way 14 Head Start families shared books with their children at home and the responses the children had to the literature they heard. The following suggestions for Head Start directors, curriculum coordinators, and teachers are implied in the results of this study:

- Demonstrate reading aloud approaches for family members (Darling & Lee, 2004).

- Model ways to extend literature experiences by asking open-ended questions, encouraging story retelling, and initiating dramatic reenactment (Jordan, Snow, & Porche, 2000; Lilly & Green, 2004).

- Provide information on genres of literature and ways to evaluate the quality of books.

- Make books more accessible to families by organizing a family lending library where families can check out books and related props (Brock & Dodd, 1994).

- Propose ways that families can share books with children in various places and at different times of day (e.g., after school, while supper is cooking, during car trips).

- Share information on library resources and cards (Anderson, 2000).

The message that reading aloud is crucial to independent reading and later achievement had certainly reached the families who participated in this study. Their willingness to share their family literacy practices was admirable and encouraging. If Head Start educators could build on this enthusiasm by providing workshops and information to help families extend and expand read-aloud experiences, the sharing of books might be even more worthwhile.

References

Anderson, Sherlie A. (2000). How parental involvement makes a difference in reading achievement. Reading Improvement, 37(2), 61-86. EJ 611 093.

Aulls, Mark W., & Sollars, Valerie. (2003). The differential influence of the home environment on the reading ability of children entering grade one. Reading Improvement, 40(4), 164-178.

Baker, Linda; Sonnenschein, Susan; Serpell, Robert; Scher, Deborah; Fernandez-Fein, Sylvia; Munsterman, Kimberly; Hill, Susan; Goddard-Truitt, Victoria; & Danseco, Evangeline. (1996). Early literacy at home: Children's experiences and parents' perspectives. Reading Teacher, 50(1), 70-72. EJ 533 989.

Beck, Isabel L., & McKeown, Margaret G. (2001). Text talk: Capturing the benefits of read-aloud experiences for young children. Reading Teacher, 55(1), 10-20. EJ 632 232.

Bogdan, Robert C., & Biklen, Sari K. (1982). Qualitative research for education. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Bracey, Gerald W. (2000). A child's garden no more. Phi Delta Kappan, 81(9), 712-713. EJ 606 466.

Brock, Dana R., & Dodd, Elizabeth L. (1994). A family lending library: Promoting early literacy development. Young Children, 49(3), 16-21. EJ 479 988.

Clay, Marie M. (1991). Becoming literate: The construction of inner control. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Cochran-Smith, Marilyn. (1984). The making of a reader. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. ED 265 507.

Darigan, Daniel L.; Tunnell, Michael O.; & Jacobs, James S. (2002). Children's literature: Engaging teachers and children in good books. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Darling, Sharon, & Lee, Jon. (2004). Linking parents to reading instruction. Reading Teacher, 57(4), 382-384.

Duke, Nell K. (2000). For the rich it's richer: Print experiences and environments offered to children in very low- and very high-socioeconomic status first-grade classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 441-478. EJ 624 130.

Feitelson, Dina; Kita, Bracha; & Goldstein, Zahava. (1986). Effects of listening to series stories on first graders' comprehension and use of language. Research in the Teaching of English, 20(4), 339-353. EJ 345 187.

Green, Connie R.; Lilly, Elizabeth; & Barrett, Theresa M. (2002). Connecting literature and life: Young children and families sharing books. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 16(2), 248-262. EJ 654 383.

Hannon, Peter. (1998). How we can foster children's early literacy development through parent involvement. In Susan B. Newman & Kathleen A. Roskos (Eds.), Children achieving: Best practices in early literacy (pp. 123-131). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. ED 437 649.

Harste, Jerome C.; Woodward, Virginia A.; & Burke, Carolyn L. (1984). Language stories and literacy lessons. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. ED 257 113.

Hart, Betty, & Risley, Todd R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. ED 387 210.

Haycock, Ken. (2003). Closing the disparity gap. Teacher Librarian, 30(4), 38.

Jordan, Gail E.; Snow, Catherine E.; & Porche, Michelle V. (2000). Project EASE: The effect of a family literacy project on kindergarten students' early literacy skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 35(4), 524-546. EJ 616 175.

Krashen, Stephen. (1993). The power of reading: Insights from the research. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Lilly, Elizabeth, & Green, Connie. (2004). Developing partnerships with families through children's literature. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

MacLean, Morag; Bryant, Peter; & Bradley, Lynette. (1987), Rhymes, nursery rhymes and reading in early childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33(3), 255-281. EJ 361 475.

Martello, Julie. (2002). Many roads through many modes: Becoming literate in early childhood. In Laurie Makin & Criss Jones Diaz, Literacies in early childhood: Changing views challenging practice. Sydney, Australia: MacLennan & Petty. ED 475 381.

Morrow, Lesley Mandel (Ed.). (1995). Family literacy: Connections in schools and communities. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. ED 383 995.

Nespeca, Sue McCleaf. (1995). Parental involvement in emergent literacy skills of urban Head Start children. Early Childhood Development and Care, 111, 153-180. EJ 508 888.

Neuman, Susan B. (1996). Children engaging in storybook reading: The influence of access to print resources, opportunity, and parental interaction. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 11(4), 495-513. EJ 550 960.

Neuman, Susan B.; Celano, Donna C.; Greco, Albert N.; & Shue, Pamela. (2001). Access for all: Closing the book gap for children in early childhood education. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. ED 458 569.

Nord, Christine Winquist; Lennon, Jean; Liu, Baiming; & Chandler, Kathryn. (2000). Home literacy activities and signs of children's emergent literacy, 1993 and 1999. Statistics in brief (NCES 2000-026). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. ED 438 528.

Pellegrini, A. D; Galda, Lee; Jones, Ithel; & Perlmutter, Jane. (1995). Joint reading between mothers and their Head Start children: Vocabulary development in two text formats. Discourse Processes, 19(3), 441-463. EJ 511 440.

Rowe, Deborah Wells. (1998). The literate potentials of book-related dramatic play. Reading Research Quarterly, 33(1), 10-35. EJ 559 451.

Rush, Karen L. (1999). Caregiver-child interactions and early literacy development of preschool children from low-income environments. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 19(1), 3-16. EJ 583 793.

Schieffelin, Bambi B., & Cochran-Smith, Marilyn. (1984). Learning to read culturally: Literacy before schooling. In Hillel Goelman, Antoinette A. Oberg, & Frank Smith (Eds.), Awakening to literacy (pp. 3-23). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. ED 248 483.

Sherman, Robert R., & Webb, Rodman B. (1997). Qualitative research in education: Focus and methods. Philadelphia, PA: Falmer.

Smith, Courtney; Constantino, Rebecca; & Krashen, Stephen. (1997). Differences in print environment for children in Beverly Hills, Compton, and Watts. Emergency Librarian, 24(4), 8-10. EJ 544 813.

Snow, Catherine E.; Burns, M. Susan; & Griffin, Peg (Eds.). (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. ED 416 465.

Taylor, Denny (Ed.). (1997). Many families, many literacies. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Valdez-Menchaca, Marta C., & Whitehurst, Grover J. (1992). Accelerating language development through picture book reading: A systematic extension in Mexican day care. Developmental Psychology, 28(6), 1106-1114. EJ 454 910.

Whitehurst, Grover J.; Arnold, David S; Epstein, Jeffrey N.; Angell, Andrea L.; Smith, M.; & Fischel, J. (1994). A picture book reading intervention in day care and home for children from low-income families. Developmental Psychology, 30(5), 679-689. EJ 493 520.

Wolf, Shelby Anne, & Heath, Shirley Brice. (1992). The braid of literature: Children's worlds of reading. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Children's Books Cited

Bemelmans, Ludwig. (1939). Madeline. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Brown, Margaret Wise. (1990). Buenas noches, Luna (Clement Hurd, Ill.). New York: Lectorum.

Brown, Margaret Wise. (2000). The sailor dog. New York: Golden Books.

Charles, Faustin. (1999). The selfish crocodile (Michael Terry, Ill.). New York: Little Tiger Press.

David, Luke. (1998). The rugrats versus the monkeys. New York: Simon Spotlight/Nickelodeon.

Findlay, Lisa (adapter). (2004). Walt Disney's Cinderella. New York: Random House.

Golden Books. (1997). I love nursery rhymes (Barney). New York: Golden Books.

Hazen, Barbara Shook. (1983). Tight times (Trina Schart Hyman, Ill.). New York: Penguin Putnam.

Hutchins, Pat. (1998). Rosie's walk. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Johnson, Crockett. (1983). Harold and the purple crayon. New York: HarperCollins.

Keats, Ezra Jacks. (1967). Peter's chair. New York: Harper & Row.

Kraus, Robert. (1971). Leo the late bloomer (Jose Aruego, Ill.). New York: Windmill Press.

Lionni, Leo. (1963). Swimmy. New York: Dragonfly Books.

London, Jonathan. (1995). Froggy gets dressed (Frank Remkiewicz, Ill.). New York: Scholastic.

London, Jonathan. (2002). Froggy goes to bed (Frank Remkiewicz, Ill.). New York: Scholastic.

Numeroff, Laura Joffe. (1985). If you give a mouse a cookie (Felicia Bond, Ill.). New York: Harper & Row.

Numeroff, Laura. (1998). If you give a pig a pancake (Felicia Bond, Ill.). New York: HarperCollins.

Parker, Kristy. (1990). My dad, the magnificent (Lillian Hoban, Ill.). New York: Penguin Putnam.

Perrault, Charles. (1999). Cinderella. (Anthea. Bell, Trans.). New York: North-South Books.

Piper, Watty. (1961). The little engine that could (George Hauman & Doris Hauman, Ill.). New York: Platt & Munk.

Sendak, Maurice. (1963). Where the wild things are. New York: HarperCollins.

Seuss, Dr. (1988). The foot book. New York: Random House.

Silverhardt, Lauryn. (adapter). (2004). Rubbadubbers underwater adventures. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Shannon, David. (1999). No, David! New York: Scholastic.

Williams, Margery. (1983). The velveteen rabbit (Allen Atkinson, Ill.) New York: Knopf.

Author Information

Connie Green is a professor in the Department of Language, Reading, and Exceptionalities and the Birth through Kindergarten program at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. Her research interests include emergent literacy, family involvement, and the role of religion in public education. She is a coauthor of Developing Partnerships with Families through Children's Literature. Dr. Green is currently on off-campus scholarly assignment teaching a public school More at Four prekindergarten class.

Connie R. Green

Professor

,

Reading, & Exceptionalities

P.O. Box 32085

Appalachian State University

Boone, NC 28608

Telephone: 828-262-2195

Email: greencr@appstate.edu

Sharen W. Halsall is assistant director/elementary coordinator in the School of Teaching and Learning, College of Education, University of Florida. She has taught over 10 years in elementary classrooms and early childhood special education settings. Following the completion of her Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction in early childhood, Dr. Halsall became coordinator of child development at Santa Fe Community College, where she wrote personnel preparation grants and worked on articulation of programming between community colleges and university teacher education programs. Dr. Halsall joined the faculty at the University of Florida in March 2000. In addition to teaching, she is responsible for coordinating the Unified Elementary Proteach field experiences, and she serves as a liaison with the local school districts in the planning, designing, and assessment of field experiences.

Sharen W. Halsall

Elementary Coordinator

School of Teaching & Learning

University of Florida

College of Education

P.O. Box 117048

Gainesville, FL 32611

Telephone: 352-392-9191

Email: swhalsall@coe.ufl.edu