Volume 3 Number 2

©The Author(s) 2001

Purposeful Learning: A Study of Water

Abstract

This article describes a project on water undertaken by kindergartners. The article first lists criteria that help determine the merit of a topic for study. A discussion of how the water project emerged follows. Preliminary work by the teachers, the formation of groups to explore specific aspects of water, and the results of each group's work are then discussed. The role of the teacher in providing teacher-directed activities to complement project work is presented. The article also examines how the activities undertaken during a project meet state and local standards.

Introduction

My teaching style has been greatly influenced by the work of Lilian Katz, Sylvia Chard, and the Reggio Emilia approach to early education. In my classroom of kindergartners, I have seen evidence that learning and growth in all areas have been greatly enhanced through the process of study or project work. Integrating curriculum learning around a study not only helps children make strong and relevant connections to real-life inquiries, it also builds a sense of community, democracy, and empowerment for the group and for each individual child who plays a role in the process. My role as facilitator is to guide the process; to assist in developing the study; to gather resources, including planning trips or arranging for guest speakers; and to reflect on and assess the development of the project and the children's experiences.

As a teacher in a public school setting, I am well aware of my responsibility to incorporate meeting district and state standards into children's experiences. I do feel it is my responsibility as the classroom teacher to provide ample opportunities for the children in my class to experience purposeful activities that will further growth and development in every area. My goal is to weave the learning of these proficiencies into the tapestry of naturalistic early childhood explorations. The focus of our learning goes far beyond learning a set of proficiencies. For me, the main criteria for determining the merit of a study are whether a topic provides:

- opportunities to pursue real inquiries

- opportunities for teamwork and community building

- opportunities for individual strengths to shine

- opportunities to showcase learning as a journey of exciting discovery and exploration

- opportunities for incorporating the learning of knowledge and skills relevant to development across ALL content areas

These criteria will be examined in more detail as we take a closer look at our study of water.

Emerging Project

Clear Creek Elementary School houses approximately 550 children. Bloomington is home to Indiana University's main campus. Our school is located on the southern outskirts of the city, bringing together a broad mix of families—some affiliated with the university and others residing in rural areas. We usually have four sections of half-day kindergarten divided between two teachers. At the time of this project, my kindergarten classes were composed of 18 children in the morning and 16 in the afternoon. I had a full-day student teacher for eight weeks of our project from January until March. An aide also accompanied a child with special needs in my afternoon class each day. Our teaching team also included our wonderful parent volunteers and other university practicum students.

Our study of water began in December. We had completed a lengthy project on the Olympics during September and October. In November, I initiated a study on "The Sky"—one of our adopted science series units. I wondered if kindergartners could grasp the abstract nature of things so distant, but I hoped that at some level they could connect with the theme. After all, it is a part of their visual world. They certainly relate to night and day, and they have had interest in clouds, storms, and the moon and sun. We had been enjoying reading popular American tall tales and folklore. From this point, we started reading some Native American tales about the stars and the characters and stories they represented to these storytellers. We created punched-hole constellation pictures on paper and made constellations in a box and on our Lite Brite. We looked through telescopes and enjoyed seeing things far away. A few children connected with our activities, and their work lingered. For others, the project lost steam quickly. Perhaps my own interest and energy waned. We were saved by a cold and snowy week in December.

Our "Sky" project seemed barely off the ground when a big winter snow arrived two weeks before winter vacation. Our attention immediately shifted from stars to snow. We brought some snow inside and played in it and watched it melt. We mixed colors into it and took its temperature. When it snowed more, we looked at the crystals on black paper. We had many enthusiastic questions about the snow and the water that came after the melt. Where did the snow come from? Where did it go when it melted? Why did the sun melt the snow faster? How did the sidewalk get dry if snow cannot melt into the sidewalk? These were just a few of many questions. As I went through the criteria, I felt that studying water had merit for these young children. It held the most important elements—interest, enthusiasm, and relevance. It also provided many opportunities for experiential learning across curricular areas.

Preliminary Work

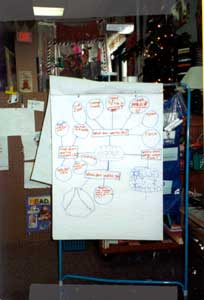

When my student teacher, Jean Salamon, arrived in January, following winter break, we really plunged into our study. We did much preliminary work, organizing groups or "committees" that would fit our main themes, which centered on the children's questions. We gathered many resources, including books (fact and fiction), pictures of water, tapes of the sounds of water, and videotapes of bodies of water and weather-related water. We brainstormed our own list of possible activities involving learning in main areas such as language, math, and science, as well as incorporating motor/movement, artistic expression, and music. We talked about how we would work on a study as a community, as a whole group, and in small groups. We talked about the logistics and scheduling of study work as it would fit into our day. Jean and I felt that this type of preliminary work was critical to the success of our study. Forming our study groups started us off on our project web. The children's questions about water seemed to form four distinct groups, and four groups, or "committees," seemed to work well logistically. The "committee" names were (1) Where does water come from? (2) Where does water go? (3) What can water do? (4) How does water support life? The latter question evolved because of prior interest in water creatures—an earlier untapped interest. The children picked the committee that interested them most as we gave examples of the possible activities involved. We started our web about water with water in the center and our four group questions in array. Our study was underway.

Committee Work Begins

Our committees were eager to get started. Each day at our whole group opening meeting, we would reflect on our progress and discuss the plans for the day related to our project work. The adults usually met with two committees a day during our "choice" time. This strategy seemed to work best for us. Meetings lasted initially 15-20 minutes, allowing plenty of personal choice time for the children. The children decided that personal choice time was important to everyone. Our project work was conducted mostly in the form of small group meetings, while others were involved in personal choices. Some days, especially toward the beginning and end of the project, whole group activities related to the study were planned.

As the project web began to take shape and we had some direction, each group went to the library to find resources. Each of the four committees met with an adult to brainstorm ideas for possible activities, to make resource lists, and to draw plans as necessary. Documentation of the project by teachers and by children was an important part of the process. We kept copies of our notes, lists, and plans in committee folders throughout the study, which later became part of our document board and our final project book. Each committee had a different focus and consequently decided on widely varying activities, experiments, and so forth that would help the class learn and find answers to our questions about water. Each committee's charge was to research water as it related to its study question, experiment with various activities that demonstrated the learned principles, then implement activities with the rest of the class to teach others those principles. Some committees selected one main activity; others chose several activities that were appropriate for their topic. Documenting the children's work as they went through these steps was an important part of the process. Documentation took the form of drawings, diagrams, writings, photographs, and models, and was implemented mostly by children with adult support.

The water web.

The water web.

The Work of Four Committees

Committee 1. Where Does Water Come from?

This group addressed the question we had about the snow falling from the sky. The class wanted to understand more about precipitation. The adults found some great resource books written for young children on projects and experiments on the topic of water. We marked the pages on evaporation and the water cycle for the committee. The children decided on one evaporation experiment with an activity called "rain in a bag." Over the course of the week, they made their own prototypes of the rain activity to test. The committee members introduced and set up the evaporation experiment for the whole class. During week 3, they set up a center during choice time for everyone to come and make their own rain in a bag. The children and adults took pictures to document the work of the committee and the class. During whole group meetings, the committees explained their discoveries, their progress, and how they wanted the whole class to be involved.

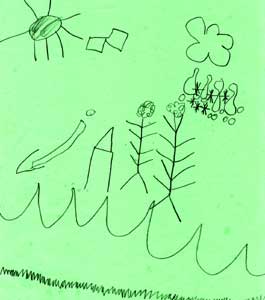

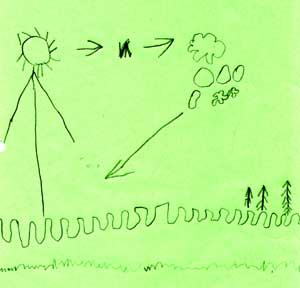

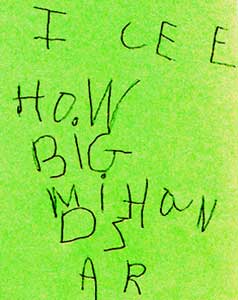

The children documented what they learned about the water cycle.

The children documented what they learned about the water cycle.

Committee 1 set up a rain-in-a-bag activity.

Committee 1 set up a rain-in-a-bag activity.

Committee 2. Where Does Water Go?

The children were intrigued as we watched an old classic film about a boy who made a little wooden canoe and set it afloat atop a mountainside, hoping that it would travel safely all the way to the sea. The children drew in their journals as they watched the film, noting things and obstacles encountered by the boat along the path and mapping the journey as it went from small stream to river to lake and finally to the sea. We took a walk along a creekbed on our school grounds. The children sat on the bridge to draw pictures of the creekbed and the things along the banks. The committee decided they wanted to make a large model of a riverbed to demonstrate the journey a boat might take from a mountaintop to the sea. They made initial plans (maps) on paper. They used clay, Playdough, and Model Magic to construct a mountain and riverbed in our sandbox. A plastic tray became the large body of water at the end of the journey. The children examined pictures and books and used their own knowledge of water areas to add props such as sand, shells, and trees. They also wanted to construct a bridge across the narrow river, which suited the engineering enthusiasts. Finally, they made a little clay boat to bravely embark on the journey from mountain to sea. They had invited others to assist in the construction along the way. The culmination was the launching of the boat by the whole class. Modifications over the course of a week were needed to enhance a smoother journey for the boat!

Committee 2 decided to make a model of a riverbed to demonstrate

the journey a boat might take from a mountaintop to the sea.

Committee 2 decided to make a model of a riverbed to demonstrate

the journey a boat might take from a mountaintop to the sea.

The children planned their model on paper and used clay to

make the mountain and a plastic tray for the water feature.

The children planned their model on paper and used clay to

make the mountain and a plastic tray for the water feature.

Committee 3. What Can Water Do?

This topic was broad! Adult help was necessary to guide the direction of the work of this group. The children were looking for answers to questions involving changing states of water and water's effect on other things. As we looked at our resource books, the children also became interested in how water can change the way things look or sound. We wanted them to explore other properties of water as well—for example, water has weight, water can change its form, water takes up space. The committee picked several activities/experiments to set up for the class. As with all the committees, we experimented as a group before introducing an activity to the whole class. The group conducted sink-and-float exploration in the water table. We examined various materials that would make a good boat and then tested them out. They made a magnifying lens with water and set up a refraction tank in the science area. At the water table, they set up metal pipes to bang on and experiment with water and sounds. They also set up musical water jars. During the last week of the project, this committee implemented an experiment demonstrating water and force. The committee demonstrated to the whole class an experiment looking at mixing of substances in water. This experiment, called "water volcano," mixed hot, colored water in a bottle submerged with an open lid in a tank of cold water. The children drew in their journals as they watched. They also demonstrated the dissolving of salt and other substances in water. This group never tired of its work, and the rest of the class was eager to visit their interactive and exciting exhibits!

Committee 3 made a magnifying lens with water and set up a refraction tank in the science area.

Committee 3 made a magnifying lens with water and set up a refraction tank in the science area.

The children set up musical water jars and metal pipes to bang on and experiment with water and sounds.

The children set up musical water jars and metal pipes to bang on and experiment with water and sounds.

The children also demonstrated water and force.

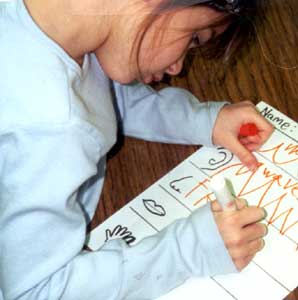

While listening to taped sounds of moving water, children documented

how they could use each of their senses while exploring water.

The children also demonstrated water and force.

While listening to taped sounds of moving water, children documented

how they could use each of their senses while exploring water.

Committee 4. How Does Water Support Life?

This committee attracted our nature lovers. They wanted new classroom pets! The children looked through books on water creatures and pooled their knowledge about living things that we could have in the classroom. In retrospect, a visit to a pet store, or a visit from a pet store worker, would have been of benefit. Through their reading, the children learned that some creatures, such as turtles, could carry diseases and would not be appropriate for the classroom.

Lists were made of possible creatures, and the children settled on two—a crayfish and a frog. These creatures were purchased, and the children worked on their habitats and continued their care. They shared their knowledge with the others about the dependence of the animals on water and other particulars. As part of their work, they also collected water from various sites, our creatures' habitats, a local creek, and a backyard pond.

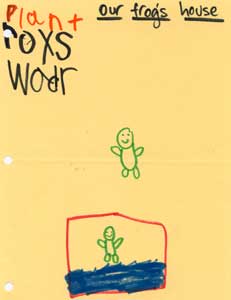

A member of Committee 4 drew our frog's house.

A member of Committee 4 drew our frog's house.

Committee members set up a learning activity and invited others to look at drops of water under microscopes to search for substances—living or nonliving. My student teacher and I also wanted to link water with human life. We extended the focus beyond the group's interest by showing a science video on water usage and conservation. The children were amazed to see a visual demonstration of how much water one person uses in a day—over 100 gallons! Through a whole group discussion, the children decided they wanted to see if they could collect 100 gallon milk jugs, as seen on the video, to see how much this amount really was. As the children brought in milk jugs from home, I strung them along the ceiling in our room, marking groups of 10. They were also intrigued with how water gets from bodies of water to our homes. We looked at Magic School Bus at the Water Works and used our big box of PVC pipe and boxes to bring water to our "homes." A trip to our city water plant or a visit from a plumber would also have been of benefit.

The children used microscopes to look for living and nonliving substances in the pond water.

The children used microscopes to look for living and nonliving substances in the pond water.

An Interest Group: Our Water World

Meanwhile... our class project web took a new direction. There are many children in the class who thrive on daily dramatic play and large motor movement. A small group of children decided to turn our house area into a water world. Those interested made a list of what was to be included. We had read great books about different kinds of boats, and one student had just returned from a cruise. He brought in brochures and pictures from his trip. Some parents who had been on boating trips also brought in artifacts. The teachers contributed four large boxes, an anchor, life jackets, and an underwater scene shower curtain for the floor; the children created the rest. In the art area, our artists made water creatures and stars, which hung from our sky above on netting. They made portholes in our boats and made fishing poles to catch our dinner. They made scenery murals and posters and pictures of tropical islands. They used yarn spools to make spy glasses as they shouted "Land-Ho!" They sang pirate songs and played music from The Little Mermaid and other water-related tunes as they created and played. Along with our cruise brochures, the teachers added books about travel and exploration, past and present. Real compasses and maps were added with which children could track their journeys and record their travels. The stars also assisted our navigations. The plumbing pipes were incorporated so there could be running water and flushing toilets on the boats! Children made paper treasure boxes, with handmade jewelry, which they hid with delight. Several boys then made treasure maps at the writing table with clues as to where you might find the treasure in the water world!

A group of children turned our house area into a water world: "Land-ho!"

Water world props included a box of shells,

a treasure box with jewels, a compass,

and maps to chart our course.

A group of children turned our house area into a water world: "Land-ho!"

Water world props included a box of shells,

a treasure box with jewels, a compass,

and maps to chart our course.

Teacher Roles and Filling in Holes

Although teacher guidance was present throughout the study, visitors were amazed at the confidence children had in managing their own work. The work certainly was owned by the children. For teachers, there is great satisfaction in seeing children leading learning and gaining confidence in their abilities as learners and as contributors to a community of learners. The children conducted themselves responsibly and learned a host of management skills associated with planning, implementing, and assessing a big project. The balance of roles is a critical element for me in a classroom where we respect each other's strengths and individuality and we support each other as needed. Children need the opportunity to work in their areas of strength, which allows them to showcase their competence, while being encouraged and challenged to work in their areas of need.

My student teacher and I did fill in some holes throughout the project with teacher-planned activities to help children make further connections in their learning and to incorporate skills or learning opportunities that did not seem to surface for the group or for individuals who were "on the fringe" of participation. For example, we felt that the class needed more experience with understanding the math concept of comparing the number of objects in two groups (how many more or less?). We planned a thematically related math activity called Feed the Hungry Fish as a learning center activity to meet this need. Each child was invited to participate in small groups, with an adult, until everyone had a turn and their understanding of the concept was recorded. At times, meeting a need was as simple as providing my support as a child tried on a new role, such as my asking a child to draw a diagram for a committee when drawing was not an area of confidence for a child. I do feel it is my responsibility to see that learning takes place for ALL children in whatever form and at whatever level is appropriate for that child. Careful observation and recording are key to following the participation and experiences of each child and addressing those needs or filling in those holes. Doing projects is not an exception to that aspect of a teacher's role. Many children were using beginning reading and writing skills throughout the project. Some children were not. That was a hole for those children. Mathematics was not incorporated as much as we would have liked. That was a hole. I felt a need for more music and large motor activities. These holes were filled in through teacher-planned activities either during whole group, small group, or individual encounters. The activities may or may not have been associated with our water theme. As stated earlier, while recognizing the importance of connected, integrated learning activities, care was taken to balance our study focus time with our other regular classroom activity. Children's individual needs continued to be met whether woven into our project or through other classroom activity.

Teacher activity: How many drops of water will fit on the coin?

Teacher activity: How many drops of water will fit on the coin?

Bringing the Project to a Close

I am not sure when the project actually came to a close. The boxes were tattered and torn. Fewer visits were made to the water world. The committees stopped conducting activities. The model mountain was soggy and crumbling. Every few days, a committee enthusiast would mend a tear or patch a hole. Interest was waning. As the photos came back, we put them in a book. Our language arts practicum students helped the children reflect and write about their experiences, responding to questions such as, "What did you learn?" "What was your favorite committee activity?" "How did you use literacy, math, or science skills?" "How did you work with your peers?" A videotape was also made of our project, which due to technical problems with the camera was of very poor quality. The adults worked on a document board, which was reviewed by parents on family night and hung in our hallway for others to share in our learning journey. The contents of the document board, including photos, drawings, and our web, were later transferred to a project book, which could then be taken home by children to share with families. So much energy and enthusiasm went into our work. After the project, the children slipped into routines naturally. We took time to bask in the accomplishments and to enjoy the down time, returning to more time with old favorites in the classroom. After a big project, we wait and wonder what other encounters await us. Will a new season bring another interest to pursue? For a time, we are happy to wonder.

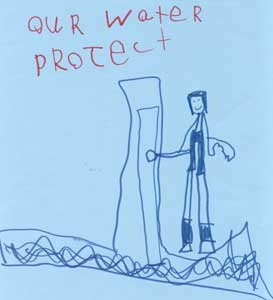

A child drew the cover for our water project book.

A child drew the cover for our water project book.

Linking: Projects and Standards

There is much emphasis these days on curricular standards. Even for the youngest children, the message is ever present. Are there general standards or developmental bottom lines for which children and teachers should be held accountable? I do not wish to engage in a discussion about the appropriateness of particular standards or of accountability issues associated with standards including standardized assessment (that would be another paper entirely!). The fact is that caregivers are responsible for developing the potential in each child through practices that are developmentally appropriate. They are responsible for keeping children safe and nurtured, and they are responsible for creating an environment where children have opportunities to test and stretch their capabilities in every arena. In my role as a public school teacher in the state of Indiana, I am obligated to assist children in reaching certain goals, as they are able. These goals include those I hold dear based on years of experience and personal research—self-worth, risk taking, problem solving, and cooperative living. They also include state and local standards, which come to me via a big red notebook. Some of these standards are very appropriate. Some are rigorous. A few may be inappropriate by my standards. In the following tables and sections, I will attempt to link the most important and appropriate standards (from my knowledge of best practices and from my little red book!) to the knowledge and skills experienced through our water study.

| Standards/Proficiencies | Project Experiences |

|---|---|

| Understand concepts about print (include letter recognition) | Reading, recording, writing, labeling throughout project |

| Phonemic awareness | Reading, recording, writing |

| Decoding/word recognition | Reading, recording, writing |

| Vocabulary/word meaning | Discussion, reading, resources, recording, labeling |

| Reading for information | Modeled reading, resource work |

| Identify structural features | Modeled reading—identified title, author Used table of contents to locate information |

| Use pictures/context/predictions to construct meaning | Reading—resource, factual, fiction, and beginning, predictable books related to topic |

| Connect text to experiences | Reading and sharing throughout project |

| Retell stories/text | Discussion/reflection throughout project |

| Identify/summarize main ideas | Whole group/committee discussions—lots of talking and sharing of ideas! |

| Fantasy/reality | Fiction vs. factual—resource materials |

| Variety of print materials | Incorporated songs, poems, rhymes related to water project |

| Identify character, setting, etc. | Book discussions, charts (We were also doing an author study of Ezra Jack Keats during this time.) |

| Identify favorite books | Graph of favorite Keats books |

| Infer characters' feelings | Chart of what we can tell about Keats and his characters |

Writing Process |

|

| Make a writing plan | Guidance in organizing/planning to write |

| Dictated writing | Some recorded writing by adults, web, charts |

| Writing/picture, letters, words for purpose | Writing/drawing in all aspects of project work for distinct purposes |

| Use various venues for writing for different purposes | Web, chart, diagrams, maps, designs, plans, lists, graphs, journal entries, class book, daily news, school news, parent news |

| Handwriting | Guided, purposeful writing |

| Spelling—using knowledge of sounds | Assisted writing/encouraging risk taking, writing/invented spellings |

Listening/Speaking |

|

| Active listening | Engaged in active, purposeful communication |

| Follow directions | Incorporated in all activities |

| Share ideas with others | Group/one-to-one discussions/committee work |

| Describe events in logical sequence | Discussions—giving directions to others |

| Recite poems, songs, rhymes | Group poems, chants, songs, rhymes |

Study Skills |

|

| Awareness of resources | Many resources gathered and used in project |

| Responsible management | Children managing is focus of project! |

| Follow a set plan | Learning to organize and follow through—being accountable to classmates is a focus |

| Standards/Proficiencies | Project Experiences |

|---|---|

| Communicate problem solving through words/drawing | Diagrams of processes/experiments |

| Compare/contrast attributes | Compared states/properties of water, volume/containers, comparing water's effect on sound/vision |

| Discriminate patterns | Talked about patterns in tides/waves, patterns on fish, pattern of rain cycle, patterns of predictable actions |

| Symbolic representation | Graphing evaporation experiment Records, charts, web, models, drawings |

| Positional relationships | Language constructing water world, mapping, drawing plans, model building |

| Use variety of strategies to solve problems | Used manipulatives to measure snow Used best materials/resources to build model (and modified for optimal use) PVC pipe construction Choosing materials/designs for experiments |

Whole Numbers |

|

| Recognize/write numbers to 21 | Measured/recorded snow depths (to 10) Measured and recorded temperatures of air, snow, water (0-45) Measured water level in evaporation jars over time |

| Compare more/less | Same as above. Feed the Hungry Fish game with dice and fish food (how many more/less) |

| Rote count to 100 | 100 gallon jugs/human water use Examined the lines on the thermometer Counted by tens to 100 |

| Put objects in groups by tens, ones | Thermometer, Feed the Hungry Fish game 100 gallon jugs in groups of 10 |

| Recognize equal parts | Snack time every day! Feed the Hungry Fish Little Blue & Little Yellow activity explored parts becoming whole/bigger |

| Use objects with simple addition and subtraction, small numbers | Feed the Hungry Fish game |

| Read/write symbols: +, -, = | Recording the Feed the Hungry Fish game |

| Use guess/check strategy | Feed the Hungry Fish game, water experiments Recorded prediction-outcome |

| Name/use/sort basic shapes | Art activities related to constructing water world and models |

| Build/create two- and three-dimensional shapes | Blocks, box boats, models, puffer fish |

Spatial Sense |

|

| Identify relative position | Boat/travel play, PVC construction |

| Nonstandard measure | Cubes and ruler to measure snow and water levels Comparative measuring in construction and PVC building |

| Time relativity | Calendar every day Tracked sun movement related to snow melting on the playground Season discussion related to weather |

| Compare objects by weight, length, volume, temperature | Water/container comparisons, evaporation experiment, snow measuring, taking temperature of air, water, snow |

| Identify coins | Teacher activity: How many drops of water will fit on the coin? |

| Standards/Proficiencies | Project Experiences |

|---|---|

| Seek knowledge/participate | Enticing, child-initiated, purposeful activities promoted participation and knowledge seeking |

| Know use for science tools | Used thermometer, microscope, telescope, magnifying lens, rulers, and balance scale |

| Teamwork in solving problems | Most activities, all committee work |

| Exploring systems | Water cycle, habitats |

| Models/simulations can be used to represent/understand real things | Water-in-a-bag activity, model, dramatic play in water world/boats/travel |

| Observe how things can change | Water-in-a-bag activity, evaporation, water volcano, water states, water and sounds/vision |

| Things are different/have different purposes/uses/attributes | Comparing/contrasting discussions/activities |

| Observe change through records and measurement | Already stated |

| Use graphs to show observations | Graphing evaporation over time |

| Estimate quantities | Feed the Hungry Fish game, snow measure |

| Classify objects by attributes | Classification game/activity |

| Make predictions | Already stated |

| Discuss reasons for ideas | Sharing, recording, journal entries |

| Difference between living/nonliving | Plants, aquatic life, water creatures and their habitats |

| Needs of living things | Care of water creatures/plants |

| Recycle | Daily! 100 gallon jugs. Children made lists of materials to acquire from the recycling center for projects. |

| People impact environment | Conservation activity, video, making dirty water, helping slow erosion |

| Recognize/name four seasons | Already stated |

| Describe kinds of weather | Already stated |

| Awareness of sun/moon/stars | Navigation/water world play, art work |

| Where food comes from | Not with this project (but we talked about what water creatures eat) |

| Tools, machines, inventions affect our lives | Books/pictures on exploration by water Tools of navigation, tools of science, plumbing! |

| Understand the human organism (health standards) | Movement activities, motor/body awareness, spatial activities (limited to these through this project) |

Social Studies

Although our district does not have social studies standards, the social benefits of constructing an integrated study are obvious. Among the benefits are that children develop a sense of their role in the community. They develop confidence as they take charge of planning, implementing activities, and sharing knowledge with their peers. There are ample opportunities to encourage even the timid student to make worthwhile contributions to the group effort and then reap the rewards of that teamwork. Children learn to listen, share, and respond to each other through positive and productive negotiation and dialogue. Together they develop plans, set goals, and work toward that end. The rewards to the teacher of observing the immense satisfaction children show when cooperation leads to success cannot be measured. It is perhaps the biggest benefit of all. I have seen my children become more confident in their abilities, socially and academically, through such work, whether it is a large project such as this one, or a smaller, shorter inquiry with a small group of interested participants.

Health/Technology

My red notebook of district proficiencies also contains standards for health and technology, which are not reviewed specifically here. Some of the health standards were certainly incorporated in our project. Many of the kindergarten health standards involve an understanding of self—who we are as living beings; how we function physically, cognitively, and emotionally; and how we relate to others in our environment. The close, cooperative work with others helped the children understand their capabilities and challenges and reflected their roles in a community activity. Caring for living creatures gave us insight into the needs of living things. Some of the technology standards were present as we explored computer programs related to water and used the computer as a resource to find answers to some of our questions. The children's writing was done by hand rather than word processing on the computer. Technology was an area that could have been integrated more into our project.

Music/Art/Motor Development

Although there are no standards for music, art, and motor development, these areas certainly carry as much weight in the early childhood classroom as any "academic" area. Music, art, and fine/gross motor experiences were purposely woven into elements of the entire project. These venues served to meet the needs of those who hold a gift and passion in those arenas, giving them a niche and opportunity to shine. They also were included in whole group activities to encourage those who would benefit from more practice and comfort in these areas.

Conclusion

In planning how I would relate our project activities to the standards, I had intended to focus only on the standards I felt were most critical to early development. However, as I was relating our activities from the project and other activities during the past months to each standard, I realized that all but a few of the complete standards were addressed by the work the children accomplished. This project was in fact most complete, encompassing every area of development and curriculum. Every child participated and contributed to the group effort in his or her own way. It is a personal goal of mine that, while implementing a project, each child has an opportunity to lead a group in an activity of strength and to gain more competence in an area of need. Part of my role as teacher is the challenging task of searching for holes that may occur for individual children. We tried to have every child participate in each of the activities, and I believe through my observations and personal documentation that my student teacher and I were fairly successful in meeting these goals. I am fortunate to have a team of adults comprising parents, university students, and special education staff in the classroom to assist in planning, implementing, and providing guidance for children. These informed adults provided the scaffolding and encouraged children to work at the edge of their potential in each of their endeavors. Records of each child's level of participation were made during some activities, but not during all. For me, assessment of children's experience and growth and of project success is an ongoing area for improvement.

In retrospect, I would also like to have included more "fieldwork" beyond our own school grounds. Field trips have been sharply discouraged of late, making it a difficult, but probably not an impossible, barrier to enhancing real, connected learning. Guest speakers would have also been of great benefit during this project. Next time!

Overall, the water project provided a multitude of enriching experiences appropriate for the kindergarten level. Every child was involved in his or her own way, and every child gained some knowledge, competence, and confidence. I am pleased that such an exciting adventure, lasting nearly a third of our school year, provided our kindergartners with the experiences that our school district, our state, and I thought to be important (and I have much higher expectations than minimum competency!). Watching the enthusiasm in the children day after day as they took the helm convinced me that the project was relevant and important for these children. It was indeed purposeful learning!

Author Information

Becky Dixon (M.S.Ed.) currently teaches kindergarten at Clear Creek Elementary School in Bloomington, Indiana. She previously worked for nearly a decade as a preschool teacher with the Indiana University Campus Children's Center. Becky works closely in teacher training with Indiana University early childhood education students. She conducts numerous lectures and workshops on a variety of topics including documenting the work of young children. She enjoys writing on education topics. Ms. Dixon was the 1999 recipient of the National Kindergarten/Early Childhood Professional Award given by Scholastic Inc., presented at the annual National Association for the Education of Young Children conference.

Becky Dixon

Clear Creek Elementary School

300 Clear Creek Dr.

Bloomington, IN 47403

Email: beckydixon2@comcast.net