Volume 2 Number 1

©The Author(s) 2000

The Project Approach: Meeting the State Standards

Abstract

This paper suggests that when engaged in project work, children apply most of the skills identified in the age-appropriate state learning standards. To illustrate how good-quality project work addresses the Illinois state learning standards, this paper describes a project conducted by a second-grade class on their community—Grafton, Illinois. The paper focuses on two children who, as part of the Grafton project, studied churches in the community. The paper describes the project's three phases and discusses how, through the process of investigating a topic of interest to them, representing their new knowledge, and sharing their work with others, the children applied the skills identified by the Illinois state learning standards as necessary for early elementary school students.

Introduction

According to Lilian Katz and Sylvia Chard (1989), a project is an in-depth investigation of a topic worthy of investigation in the students' immediate environment. By using the Project Approach to complement other parts of the curriculum, teachers can create a learning environment in which state learning standards for elementary students are addressed in an integrated and meaningful way. For example, when they are engaged in project work, children will meet many, if not most, of the state of Illinois standards for several domains in the process of investigating a topic of interest to them, representing their new knowledge, and sharing their work with others (see the Appendix for a partial list of Illinois Learning Standards for Early Elementary Grades). In addition to the skills applied in project work, other skills can be taught systematically and practiced during the course of a project. Project work intrinsically meets many of the Illinois state standards, even before considering the content of the project. Therefore, by also attending carefully to the standards relevant to the content of the project, teachers can be assured that project work is a good-quality instructional strategy that encourages children to practice and apply an abundance of skills. This article describes how a project on their community conducted in a second-grade classroom in Grafton, Illinois, helped two children meet many of the state standards for their grade level. Although this article focuses on two of the children in the class, all of their classmates had similar opportunities to acquire knowledge and practice and apply skills required in the state standards.

Project Work

Project work provides a context in which individual children or small groups of children choose an area of study that appeals to their interests and pertains directly to the project topic chosen by the class. The teacher facilitates the work as children progress through the three phases of a project (see Katz, 1994; Chard, 1998a, 1998b). In Phase 1, the teacher and the children create a topic web, or concept map, based on a discussion of the teacher's and children's knowledge and ideas related to the project topic; share personal stories; and spend ample time discussing various aspects of the topic and wondering about it. As they share their thoughts about the topic, questions arise. These questions remain open for discussion and are documented by the teacher for future reference.

During Phase 2, the children collect data (e.g., take notes, make sketches, count, and measure) during field experiences planned by the teacher. In addition, guest speakers may be invited to the classroom to answer the children's questions on the topic while they record the answers. Again, questions arise, and children begin to focus on their own areas of interest.

After choosing their area of study within the topic, children begin to seek answers to their questions as they explore, experiment, interview, survey, or use secondary sources such as books, the Internet, and encyclopedias. When sufficient data have been collected, the children choose the best modes to represent their findings (e.g., graphs, diagrams, writings, models, charts, mobiles, or murals). Along the way, they frequently share their progress with peers, teaching them what they have learned and accepting their comments and suggestions for improving their work.

In Phase 3, the culmination of the project, the children share their work with families, peers, and school and community members. State standards are met, not only through the content of the project, but through the processes of investigation and completion of products that reveal what the children have learned.

To better show how good-quality project work addresses the state learning standards, in this paper I follow two children from our second-grade classroom who took part in a project on our community—Grafton, Illinois. The Grafton project began on December 1, 1998, and ended on March 11, 1999. As part of the project, two of the children, Mark and Nora, expressed an interest in learning more about their own church in the community, St. Patrick's Church. After collecting data on their church, they decided to compare and contrast St. Patrick's Church with two other churches in the community. By following the Grafton project through each of its three phases and studying examples of the children's work, one can see clearly the goal of project work: to learn more about a worthwhile topic and to use a wide variety of skills while engaged in learning and recording the findings.

Phase 1

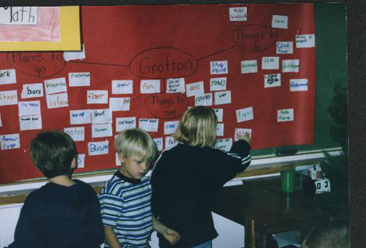

To begin Phase 1, the second-grade class made a topic web, or concept map, based on a discussion of the teacher's and children's experiences, knowledge, and ideas related to the Grafton community. The web was composed of small pieces of paper with words or phrases written on them by the children. The words or phrases were shared as a group to avoid repetition on the web. During our group sharing, we also concurred on various categories in which to organize the ideas. After printing the words or phrases on the pieces of paper, each child glued his or her own ideas near the appropriate categories (Fig. 1).

After completing the web and displaying it in the classroom, the children proceeded to brainstorm various ideas about our community, responding to several open-ended questions that I posed: "What is good about our community?" "What is bad about it?" "Where is it?" "How big is it?" "Why is it important?" "What would we do without it?" Working in cooperative learning teams and contributing answers for each question, the children then documented their collective ideas on class charts (Fig. 2). The charts were also displayed in the room for reference. As the children developed the topic web and class charts, working together to "communicate ideas in writing to accomplish a variety of purposes," they applied English/Language Arts skills identified in Goal 3 of the Illinois Learning Standards.

Figure 1. Children are engaged in writing for

the purpose of generating and organizing ideas.

Figure 1. Children are engaged in writing for

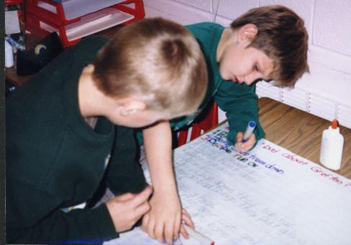

the purpose of generating and organizing ideas.  Figure 2. Cody and John work together on a chart, which documents

the collective ideas of their classmates on "What is bad about Grafton?"

Figure 2. Cody and John work together on a chart, which documents

the collective ideas of their classmates on "What is bad about Grafton?"

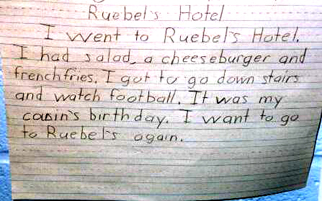

After listening to my personal story about Grafton, the children, participating in cooperative learning teams of four members each, worked in pairs as they told personal stories related to the topic. Ample time was given for them to ask each other questions about the stories. Using the "Three-Step Interview" cooperative learning structure (Kagan, 1992), the children paraphrased their partner's story and shared it with the rest of the team. Then they wrote the stories in learning centers. The stories were revised, proofread, and "published" for display (using best handwriting and correcting all mistakes). Our district, and many others, use what is called the five steps to good writing: Prewriting (making plans such as webbing), First Draft (getting ideas down on paper without conventional spelling or best handwriting), Revisions (making changes), Proofreading (checking for mistakes), and Publishing (using best handwriting and correcting all mistakes). After reading the stories aloud and sharing illustrations at group meeting, the children displayed the stories in the hall. Mark's personal story was about dining out at Ruebel's Hotel, a local restaurant and hotel that has been in our community since 1884 (Figs. 3 & 4).

Figure 3. Mark's published personal essay is in the hall

for peers, teachers, and passersby to enjoy.

Figure 3. Mark's published personal essay is in the hall

for peers, teachers, and passersby to enjoy.  Figure 4. Mark's illustration accompanies his personal essay.

Figure 4. Mark's illustration accompanies his personal essay.

From these examples of Mark's work, it can be seen that English/Language Arts Goal 1, Goal 3, and Goal 4 of the Illinois Learning Standards are addressed by sharing personal stories in the first phase of the project. By telling a personal story to his partner, Mark has presented a brief oral story to an audience. His partner listened attentively and paraphrased what he said by retelling his story to the rest of the team. Teammates had opportunities to ask questions as they each participated in the team discussion of personal stories about a common topic—their community. Mark's published personal narrative shows that he has used "correct grammar, spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and structure" to compose a well-organized personal narrative. He read it aloud to his peers "with fluency and accuracy." In addition, skills identified in the Illinois Learning Standards related to Social Science Goal 18 were practiced as peers demonstrated an understanding of "the roles of individuals in group situations."

Phase 2

Having completed and displayed our web, personal stories, and charts that documented our ideas on the topic, we began Phase 2 with several walks around the community to collect data. The data included observational drawings of buildings, notes (observations as well as answers to prewritten questions of interest), measurements of buildings, photographs, videotape, and pamphlets distributed at several community locations. The mayor of Grafton visited our classroom as well, telling us about the history of our town, sharing old photographs of buildings, and answering questions. Many of the children had already decided on their area of interest for investigation. Whenever possible, they asked questions pertaining to their subtopic of interest. After taking notes, whether from a field experience or a visiting expert, we gathered at the carpeted area in our classroom where we held our group discussions. Taking turns, each child contributed one of his or her notes while the teacher wrote the note on a large sheet of chart paper. Children who had written the same note would put a check mark beside it to eliminate repetition. By continuing in this manner until all notes were documented, we had a collective set of notes to be displayed and used for reference. Again, English/Language Arts skills stated in Illinois Learning Standards Goals 1, 3, and 4 had been practiced and applied by the children as they wrote for a specific purpose (Fig. 5), read their notes to the class, and listened to their peers' notes while discussing a common topic. Moreover, by sharing notes and documenting collective class notes, they again showed an understanding of the roles of individuals in a group situation and addressed Social Sciences Goal 18 in the Illinois Learning Standards.

Figure 5. Mark records notes and makes

an observational drawing of the church.

Figure 5. Mark records notes and makes

an observational drawing of the church.

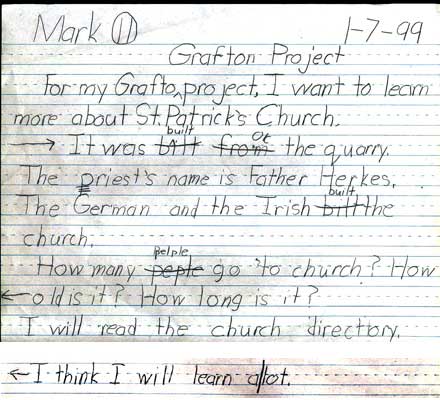

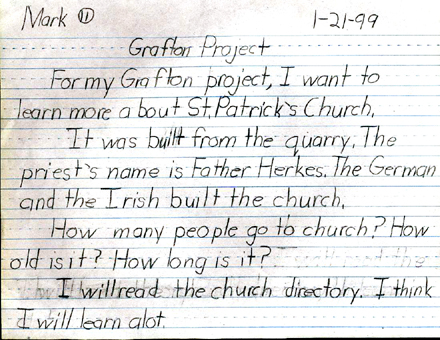

As Phase 2 continued, the children pursued topics of interest to them and formulated questions for investigation. In his four-paragraph essay (Fig. 6), Mark identified what he wanted to study, explained several things he had already learned about the topic, and listed several questions for investigation. He concluded his essay by indicating the resource he planned to use to find answers to his questions. Again, in learning centers and using the five-step writing process (Prewriting, First Draft, Revisions, Proofreading, and Publishing), Mark completed his essay and shared it with the class. The essay was then displayed for future reference. By referring to Mark's published essay (Fig. 7) as an example, we can see that the children have communicated in writing for a specific purpose and addressed Goal 3 of the English/Language Arts goals in the Illinois Learning Standards. They have also addressed English/Language Arts Goal 5 by identifying questions for research and naming the sources to be used.

Figure 6. Using proofreading marks, Mark has found

and made notations for correcting his essay.

Figure 6. Using proofreading marks, Mark has found

and made notations for correcting his essay.  Figure 7. Mark published his essay for display, using

his best handwriting and making all corrections.

Figure 7. Mark published his essay for display, using

his best handwriting and making all corrections.

Having identified questions for investigation, Mark and a classmate shared a local map to locate familiar places in the community. Mark was particularly interested in finding where East Main Street and West Main Street began because the mayor told us that the Catholic Church was built on the German end of town (west) but was given an Irish name. This decision, she explained, was a compromise between the Irish, who lived on the east end of town, and the Germans. After Mark located St. Patrick's Church on the map, he noticed that it was indeed on West Main Street. He also discovered that our own school was close to the center point of the town where the East Main addresses stopped and the West Main addresses began (Fig. 8). As Mark engaged in the investigation of the church, he practiced English/Language Arts skills stated in the Illinois Learning Standards. The skills listed under Goal 1 were applied as Mark "use[d] information presented in . . . maps . . . to form an interpretation." When he "locate[d] information using a variety of resources," he applied skills stated in Goal 5.

Figure 8. Mark studied a local map with a classmate, locating St. Patrick's

Church and finding out where East Main ends and West Main begins.

Figure 8. Mark studied a local map with a classmate, locating St. Patrick's

Church and finding out where East Main ends and West Main begins.

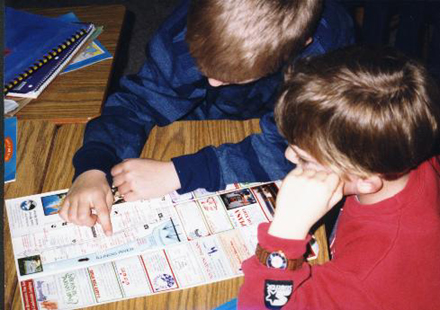

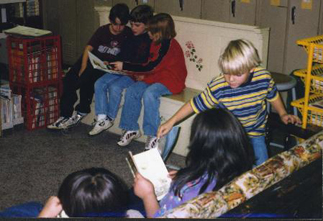

Later, Mark and Nora gathered in the reading center with several of their peers, ready to engage in research. Mark (Fig. 9, center, back bench) read the church directory as Nora and another classmate listened carefully. Mark was a gifted reader, while Nora was a strong auditory learner. As Mark and Nora read the church directory, they applied "reading strategies," and "word analysis and vocabulary skills," while reading for a specific purpose and verifying their predictions and/or linking their prior knowledge to the content of their reading. By applying these skills in their reading from a variety of sources, they addressed Goal 1 of the Illinois Learning Standards related to English/Language Arts. As they gathered information from their reading, they applied skills stated in English/Language Arts Goal 5. In addition, Goal 16 of Illinois Learning Standards related to Social Science was applied as they sought out "answers from historical sources" and identified "key individuals and events in the development of the local community."

Figure 9. Mark brought his parents' church directory to school.

He read to Nora as they searched for answers to their questions.

Figure 9. Mark brought his parents' church directory to school.

He read to Nora as they searched for answers to their questions.

Because the church building had been surrounded by deep snow when we walked past it on our field experience, we had not measured it. Mark and Nora found the dimensions of the building, however, in the church directory. They also enjoyed reading the story of the compromise between the Germans and the Irish. The directory explained, as had the mayor, that the stone used to construct the building had come from one of the old Grafton quarries that no longer existed. Mark and Nora began planning the construction of a scale model of the church. They planned, also, to make a triple Venn diagram, in order to compare and contrast all three churches in Grafton.

Mark and Nora started on the model first. Other groups planned to build models as well, so at one of our group meetings, we discussed the sizes of our models. Because of space, I asked the children what unit of measurement we might use instead of feet. Both inches and centimeters were suggested, but after trying each one, we decided on centimeters. Nora and Mark went to the "treasure room" (our room for storing boxes, paper towel rolls, egg cartons, foam meat trays, and other materials) and found a box that was very close to the dimensions they needed. Work on the model of St. Patrick's Church was then underway. For details, they referred to a photograph in the church directory, as well as their own observational drawings.

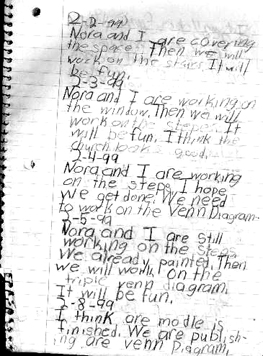

Each day, before engaging in their project work, the children were given time to record their plans in their "learning" journals. We then gathered as a group so that at least three children, whose names were drawn from a container, could read their plans to the group. We stayed in our meeting long enough to determine if anyone was having problems or needed additional supplies before beginning work. By the time the meeting ended, the children were focused on what they would be doing that morning. Encompassed in writing their plans are skills listed in the Illinois Learning Standards, specifically English/Language Arts Goals 1, 3, and 4. Children write for a specific purpose and read with fluency as the group listens attentively and participates in a discussion of the morning's work plans.

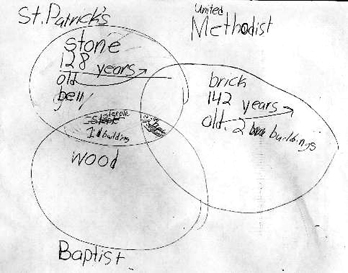

By reading Mark's learning journal entry from February 4, 1999 (Fig. 10), one can tell that he was beginning to be concerned about time. Mark and Nora decided that while Nora continued to work on the model, Mark would begin a first draft of the triple Venn diagram. They discussed what should be included in the Venn diagram before Mark began. Included in their plans for the Venn diagram were the ages of each building, the building materials, addresses, number of buildings, and whether or not each building had a steeple or bell. Their notes from field experiences and research included the date each church was constructed. To figure out the ages of each church, they decided to subtract from the present year. In Figures 11 and 12, it can be seen that Goal 5 of the English/Language Arts Illinois Learning Standards is being applied as Mark works diligently on a first draft of the Venn diagram. He and Nora have analyzed and organized their acquired information from various sources, and he is planning a format in which to communicate the information. As stated in Mathematics Goal 6, he has selected the correct computational procedure to use in order to compute the age of each church. Mathematics Goal 10 has also been applied as he collected his data, analyzed and organized it, and planned a format to "communicate the results."

Figure 10. Entries from Mark's learning journal reveal how his writing is

organized and serves the important purpose of making plans for work.

Figure 10. Entries from Mark's learning journal reveal how his writing is

organized and serves the important purpose of making plans for work.  Figure 11. Mark works on the first draft of his Venn diagram.

Figure 11. Mark works on the first draft of his Venn diagram.  Figure 12. The early work on the Venn diagram shows how Mark is organizing

his newly found information about the three churches in the community.

Figure 12. The early work on the Venn diagram shows how Mark is organizing

his newly found information about the three churches in the community.

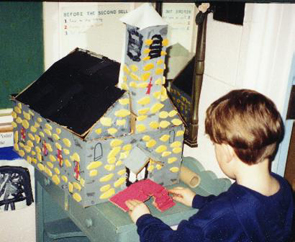

While Mark completed the final copy of the Venn diagram on poster board, Nora continued to add details to the model. After searching through the treasure room, they decided to use torn pieces from yellow foam meat trays for the stone on the building. The yellowish color resembled the stone from the old quarry that was used in many older buildings around town, including the church. Gluing on the wheelchair accessible ramp in the front of the church and constructing the top of the steeple became subsequent challenges, but Nora persevered, and, with occasional assistance and encouragement from Mark, they successfully constructed a very realistic model of the church (Figs. 13 & 14).

Figure 13. Mark admires Nora's handiwork; she persisted

in attaching the wheelchair ramp and the roof over the porch.

Figure 13. Mark admires Nora's handiwork; she persisted

in attaching the wheelchair ramp and the roof over the porch.  Figure 14. Saint Patrick's Church, Grafton, Illinois. By persisting in the long-term effort of constructing a scale model of St. Patrick's Church, Nora applied many Illinois Learning Standards. Skills listed in Mathematics Goal 7 were applied as she converted the measurements of the building from feet to centimeters and then measured cardboard boxes to find one that was nearest to the correct measurement. By referring to Figures 13 and 14, one can see that many geometric shapes were used to construct the model. The most challenging shape was the pyramid at the top of the steeple. After many trials, Nora finally discovered that by cutting four triangles, she could create the pyramid shape that she needed. By "demonstrat[ing] and apply[ing] geometric concepts" such as these, she applied the skills of Mathematics Goal 9. The end result reveals that skills stated in Science Goal 13 have also been used: the scale model was accomplished through "careful observation," accurate measurements, and reuse of discarded materials.

Figure 14. Saint Patrick's Church, Grafton, Illinois. By persisting in the long-term effort of constructing a scale model of St. Patrick's Church, Nora applied many Illinois Learning Standards. Skills listed in Mathematics Goal 7 were applied as she converted the measurements of the building from feet to centimeters and then measured cardboard boxes to find one that was nearest to the correct measurement. By referring to Figures 13 and 14, one can see that many geometric shapes were used to construct the model. The most challenging shape was the pyramid at the top of the steeple. After many trials, Nora finally discovered that by cutting four triangles, she could create the pyramid shape that she needed. By "demonstrat[ing] and apply[ing] geometric concepts" such as these, she applied the skills of Mathematics Goal 9. The end result reveals that skills stated in Science Goal 13 have also been used: the scale model was accomplished through "careful observation," accurate measurements, and reuse of discarded materials.

Every day, as the investigations progressed, we gathered as a group to give several of the individuals and small groups an opportunity to share their work. Children listened as others explained their progress, teaching them along the way. They offered comments and encouraging remarks. Often, the children gave suggestions or ideas for improving the quality of their work. Perhaps a new question would arise during the discussion, and someone would suggest a new investigation directly related to the first, as an ongoing process.

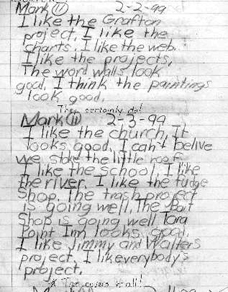

At the end of each day as well, we gathered as a group to share entries from daily journal writings. Children wrote about their progress often, and I wrote back to them each day during their silent reading so that they could also read my response to the group. Because of their ongoing interest in their progress, the children contributed their ideas for categories to be used in a rubric for evaluating their projects. Mark's daily journal entries from February 2 and 3, 1999 (Fig. 15) reveal his concern that all investigations were going well. They also show that he once again applied English/Language Arts State Goals 1, 3, and 4: focused and organized writing, ability to read the diary entry fluently to his peers, and competence in speaking in front of a group. Listening skills were exhibited on a daily basis as the children listened carefully and attentively to each other.

Figure 15. Mark writes about our progress in his daily journal.

Figure 15. Mark writes about our progress in his daily journal.

Phase 3

As Mark and Nora completed their triple Venn diagram of the three churches in Grafton and put the finishing touches on their scale model of St. Patrick's Church, they each began helping with two other student investigations. By the time we were ready for project culmination, Phase 3, our class had completed eight separate investigations of Grafton. Each of these investigations, of course, met many and various state standards, just as the project on the church did. Four scale models of local buildings had been built. A book or a web of information accompanied each of the models. Another group made a timeline to show the years that our various school buildings had been constructed or razed. Two boys interviewed the adults in the school in order to find out what trees and plants grow in Grafton. They made mobiles to indicate the names of the trees as well as leaf shapes, and they made a web to depict and label the plants. One group studied the two rivers that converge at the east end of our town. They made a map of the United States, showing the source and the mouth of the Mississippi River and the Illinois River. Their Venn diagram compared lengths, number of bordering states, sources, and mouths of each river. Another student was concerned about the trash in our town. He wrote a letter to the mayor asking what our class could do to help. He also wrote an acrostic poem about trash and printed many large signs with the poem on them. He planned to ask local merchants to hang the signs in their windows. The mayor paid a personal visit to our classroom to donate a large red trash can to be placed outside our school building to help the community with the trash problem.

The entire class was invited to participate in still another project when I asked them to contribute "Did you know?" facts and sketches for a class book. The children decided to name the book Things about Grafton That You Never Knew. Three hundred copies were printed, and a few still remain on sale in local stores.

As mentioned before, project work, independent of content, meets many state standards, simply by the investigative nature of good-quality project work. In fact, the entire English/Language Arts State Goal 5 is met in every project, no matter what the topic:

Illinois Learning Standards, English/Language Arts, State Goal 5: Use the language arts to acquire, assess and communicate information.

A. Locate, organize, and use information from various sources to

answer questions, solve problems and communicate ideas.

5.A.1a Identify questions and gather information.

5.A.1b Locate information using a variety of resources.B. Analyze and evaluate information acquired from various sources.

5.B.1a Select and organize information from various sources

for a specific purpose.

5.B.1b Cite sources used.C. Apply acquired information, concepts and ideas to communicate in

a variety of formats.

5.C.1a Write letters, reports, and stories based on acquired information.

5.C.1b Use print, nonprint, human and technological resources

to acquire and use information.

Other state standards are also related to our topic—the Grafton community. The following state standards related to our topic were met by at least one of the eight small-group investigations or through field experiences or through the visit from our mayor. State standards met by small-group investigation were taught to the whole class at group sharing time:

- Social Science State Goal 14 was addressed by one child as he showed traits of "responsible citizenship" by "working with others" to improve the quality of the environment in our community. His peers encouraged him as he made numerous signs to be placed throughout the community. After culmination, our entire class walked around town picking up litter and disposing of it properly. Many community members and business people came out to talk to us as we worked, commending the children on their display of good citizenship. In addition, the visit from the mayor had given the children an opportunity to "identify the roles of [one of our] civic leaders," yet another state standard in Social Science Goal 14.

- The two children who made a timeline about the history of our school were able to help the children "explain the difference between past, present, and future time" concerning our school. They were also able to "place themselves in time" by referring to the timeline. Their investigation had addressed Social Science State Goal 16. Each investigation of local buildings had exemplified our application of Social Science State Goal 16, as well. The children had asked "historical questions," "sought out answers from historical sources," and "identif[ied] key individuals and events in the development of the local community."

- The visit from our mayor had also addressed several aspects of Social Science Goal 16 as she talked to the children about how "the economy of the students' local community has changed over time." Grafton once had 8,000 people compared to our 612 people now. Jobs abounded in the two local quarries, boatworks building, and button factory, to mention a few. She also helped the children "identify how people . . . in the past made economic choices to survive and improve their lives" as she explained the use of metal roofs on the older buildings in order to preserve trees.

- Our visit to city hall to interview the senior citizens who had gathered there for lunch was another example of meeting Social Science State Goal 16. The children became acquainted with the senior citizen group, as well as the community members who helped serve their food. In addition, many children brought in pictures of the 1993 flood during the course of our project, helping us to "describe how the local environment has changed over time" as stated in Social Science Goal 16.

- The small group that studied the rivers contributed an abundance of information related to Social Science Goal 17. Their investigation "identif[ied] physical characteristics" of our area. The mayor had explained the importance of the rivers to our economy by "identify[ing] ways people depend on and interact with the physical environment." She had "identif[ied] . . . constraints of the physical environment" as she told the children about the numerous floods in Grafton's history. As she told about the floods, she helped them "identify changes in geographic characteristics of [our] local region." Each of these standards are included in Social Science Goal 17.

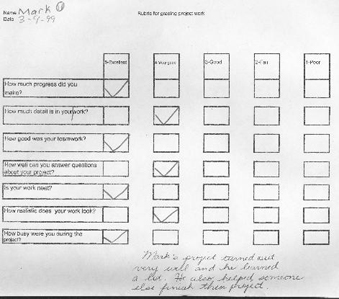

Right before project culmination, children were ready to evaluate their projects by completing their own rubric (Fig. 16) at a learning center. Knowing that a teacher's aide would be asking them questions about their investigation, the children asked if they could use their own resources for information (Venn diagrams, charts, books, and so forth). This request revealed an acute awareness of their newly acquired knowledge.

Figure 16. Mark evaluated his own project by using

the rubric that he and his classmates had developed.

Figure 16. Mark evaluated his own project by using

the rubric that he and his classmates had developed.

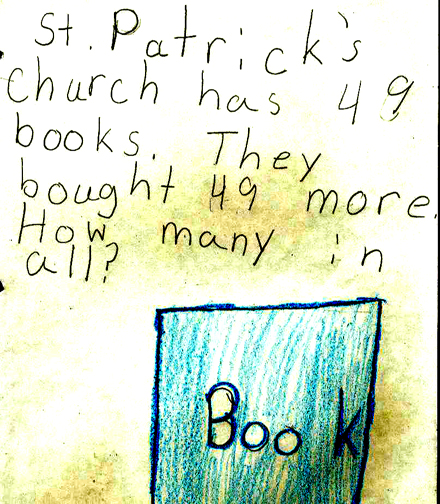

In addition to these skills that were both applied and systematically taught as a result of small-group investigations in the mornings, other skills were being taught and practiced at learning centers in the afternoons. Whenever possible, these assignments were related to the project topic. At the math center, children used English/Language Arts skills stated in Goal 3 as they wrote their own story problems (Fig. 17). The problems were published, solved by their classmates, and put into a class book. By solving the problems, the children were applying mathematics skills listed in Goal 6, specifically "select[ing] and perform[ing] computational procedures to solve problems with whole numbers."

Figure 17. Nora wrote her own math problem about the books at church.

Figure 17. Nora wrote her own math problem about the books at church.

Poetry was written at the writing center (Fig. 18), shared orally at our group meetings, and then put into another class book. Children demonstrated their application of state Goals 1, 3, and 4 related to English/Language Arts when they wrote a poem, read it to their peers, and listened attentively, recognizing poetry as a writing form.

Figure 18. Nora's poem about the church shows her enthusiasm for her work in progress.

Figure 18. Nora's poem about the church shows her enthusiasm for her work in progress.

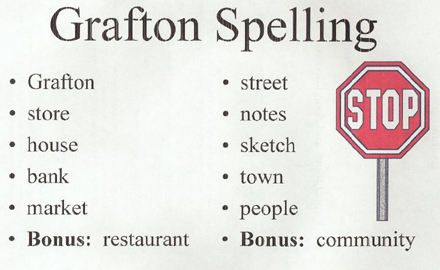

Project-related spelling words were sometimes assigned (Fig. 19). "Correct spelling of appropriate high-frequency words," a skill listed in Goal 3 related to English/Language Arts, was yet another Illinois Learning Standard applied during the project.

Figure 19. Assigned spelling words for the week were often project related.

Figure 19. Assigned spelling words for the week were often project related.

A learning center assignment on opposites contributed yet another class book (Fig. 20). The assignment also created an additional opportunity to practice English/Language Arts skills included in state Goal 1, "Read with understanding and fluency" or, specifically, "Apply word analysis skills to recognize new words."

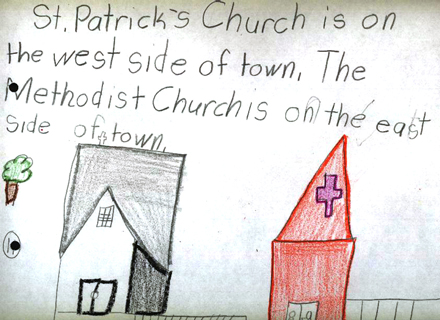

Figure 20. Mark used the opposite words east and west to

describe the location of two local churches.

Figure 20. Mark used the opposite words east and west to

describe the location of two local churches.

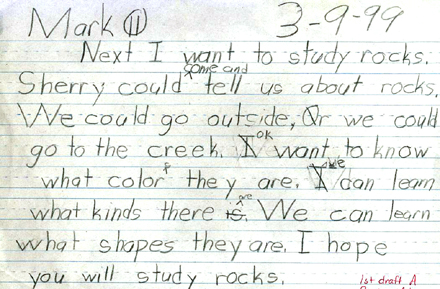

As project culmination approached, the children and I began discussing what topic to study next. Many good ideas surfaced. I used this opportunity to teach the children about persuasive writing and then asked them to write essays on the topics they would like to study next. Each persuasive essay was published and shared orally with the class, after which we voted to see which was the favorite topic. Once again, English/Language Arts skills in Goals 1, 3, and 4 were put to use as the children carefully drafted, revised, proofread, and published their essays (Fig. 21); read "aloud with fluency and accuracy"; and listened attentively to each other before the vote was conducted. By participating in the voting process, the students practiced Social Science Goal 18 as they demonstrated their understanding of the role of each individual in the group voting situation.

Figure 21. With his persuasive essay, Mark wished to convince his peers to study rocks next.

Figure 21. With his persuasive essay, Mark wished to convince his peers to study rocks next.

Conclusion

Instead of thinking of "teaching" as providing instruction in one subject area at a time, we can think of teaching as one part of the learning process. The topic, the end results, and the learning process are all equally important in project work. The learning process becomes an intricate tapestry of children and teachers working toward a common goal: to learn more about the topic while practicing curriculum skills and sharing new knowledge with peers, family, and school and community members.

When using the Project Approach to study a topic from the immediate environment in depth, state standards are met in an integrated way, rather than through segmented subject areas. Rather than being an "add-in" to an already congested school day, project work helps integrate learning in several areas and offers an approach to meaningful learning. Children practice and apply many skills in order to identify a topic, investigate questions, represent their findings, and share them with others. Children acquire skills in the natural course of meeting their personal goals. Other skills may be taught systematically, but often in the context of a project.

After hearing about our project work, teachers frequently ask me: "When do you have time to teach the curriculum?" Rather than not having enough time to teach curriculum skills, I have found that the reverse is true—by using project work and learning centers in large blocks of time, curriculum skills are abundantly practiced and applied. Children enjoy learning on their own and from each other. The teacher enjoys watching, listening, collaborating, facilitating, and participating in the learning process. The process of learning, practicing, and meeting the state learning standards becomes an interactive, purposeful, and enjoyable experience.

References

Chard, Sylvia C. (1998a). The project approach: Developing the basic framework. Practical guide 1. New York: Scholastic. ED 420 362.

Chard, Sylvia C. (1998b). The project approach: Developing curriculum with children. Practical guide 2. New York: Scholastic. ED 420 363.

Illinois State Board of Education. (1997). Illinois learning standards. Springfield, IL: Author. ED 410 667.

Kagan, Spencer (Ed.). (1992). Cooperative learning. San Juan Capistrano, CA: Resources for Teachers.

Katz, Lilian G. (1994). The project approach. ERIC Digest. Champaign, IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education. ED 368 509.

Katz, Lilian G., & Chard, Sylvia C. (1989). Engaging children's minds: The project approach. Greenwich, CT: Ablex. ED 407 074.

Author Information

Dot Schuler (M.S.Ed.) is the second-grade teacher at Grafton Elementary School in Grafton, Illinois. She previously taught kindergarten in Dow, Illinois, third grade in Arlington, Virginia, and fourth grade in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. She has written an article titled "Teaching Project Skills with a Mini-Project" in The Project Approach Catalog 2 (ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education, 1998). She also has a forthcoming article in Social Education; the title of the article is "In-depth Study of the Community." She has presented numerous workshops on the Project Approach and teaches a summer class on the Project Approach at Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville.

Dot Schuler

Second-Grade Teacher

Grafton Elementary School

P.O. Box 205

Grafton, IL 62037

Email: dschuler@jersey100.k12.il.us

Appendix

Selected Illinois Learning Standards

The learning standards listed in this article are excerpted from the Illinois Learning Standards for Early Elementary Grades adopted July 1997 by the Illinois State Board of Education. A complete list of the Illinois Learning Standards is available at http://www.isbe.state.il.us/ils/standards.html

Illinois Learning Standards, English/Language Arts, State Goal 1: Read with understanding and fluency.

A. Apply word analysis and vocabulary skills to comprehend selections.

1.A.1a Apply word analysis skills (e.g., phonics, word patterns) to recognize new words.

1.A.1b Comprehend unfamiliar words using context clues and prior knowledge; verify meanings with resource materials.

B. Apply reading strategies to improve understanding and fluency.

1.B.1a Establish purposes for reading, make predictions, connect important ideas, and link text to previous experiences and knowledge.

1.B.1b Identify genres (forms and purposes) of fiction, nonfiction, poetry and electronic literary forms.

1.B.1d Read age-appropriate material aloud with fluency and accuracy.

C. Comprehend a broad range of reading materials.

1.C.1a Use information to form questions and verify predictions.

1.C.1f Use information presented in simple tables, maps and charts to form an interpretation.

Illinois Learning Standards, English/Language Arts, State Goal 3: Write to communicate for a variety of purposes.

A. Use correct grammar, spelling, punctuation, capitalization and structure.

3.A.1a Construct complete sentences . . ., appropriate capitalization and punctuation; correct spelling of appropriate high-frequency words. . . .

B. Compose well-organized and coherent writing for specific purposes and audiences.

3.B.1a Use prewriting strategies to generate and organize ideas.

3.B.1b Demonstrate focus and organization . . . in written composition.

C. Communicate ideas in writing to accomplish a variety of purposes.

3.C.1a Write for a variety of purposes including description, information, explanation, persuasion and narration.

Illinois Learning Standards, English/Language Arts, State Goal 4: Listen and speak effectively in a variety of situations.

A. Listen effectively in formal and informal situations.

4.A.1a Listen attentively . . . and paraphrase what is said.

4.A.1b Ask questions and respond to questions from the teacher and from group members to improve comprehension.

B. Speak effectively using language appropriate to the situation and audience. . . .

4.B.1a Present brief oral reports, using language and vocabulary appropriate to the message and audience.

4.B.1b Participate in discussions around a common topic.

Illinois Learning Standards, English/Language Arts, State Goal 5: Use the language arts to acquire, assess and communicate information.

A. Locate, organize, and use information from various sources to answer questions, solve problems and communicate ideas.

5.A.1a Identify questions and gather information.

5.A.1b Locate information using a variety of resources.

B. Analyze and evaluate information acquired from various sources.

5.B.1a Select and organize information from various sources for a specific purpose.

5.B.1b Cite sources used.

C. Apply acquired information, concepts and ideas to communicate in a variety of formats.

5.C.1a Write letters, reports and stories based on acquired information.

5.C.1b Use print, nonprint, human and technological resources to acquire and use information.

Illinois Learning Standards, Mathematics, State Goal 6: Demonstrate and apply a knowledge and sense of numbers, including numeration and operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division), patterns, ratios and proportions.

C. Compute and estimate using mental mathematics, paper-and-pencil methods, calculators and computers.

6.C.1a Select and perform computational procedures to solve problems with whole numbers.

Illinois Learning Standards, Mathematics, State Goal 7: Estimate, make and use measurements of objects, quantities and relationships and determine acceptable levels of accuracy.

A. Measure and compare quantities using appropriate units, instruments and methods.

7.A.1a Measure length, volume and weight/mass using rulers, scales and other appropriate measuring instruments in the customary and metric systems.

Illinois Learning Standards, Mathematics, State Goal 9: Use geometric methods to analyze, categorize and draw conclusions about points, lines, planes and space.

A. Demonstrate and apply geometric concepts involving points, lines, planes and space.

9.A.1a Identify related two- and three-dimensional shapes including circle-sphere, square-cube, triangle-pyramid, rectangle-rectangular prism and their basic properties.

9.A.1b Draw two-dimensional shapes.

B. Identify, describe, classify and compare relationships using points, lines, planes and solids.

9.B.1a Identify and describe characteristics, similarities and differences of geometric shapes.

Illinois Learning Standards, Mathematics, State Goal 10: Collect, organize and analyze data using statistical methods; predict results; and interpret uncertainty using concepts of probability.

A. Organize, describe and make predictions from existing data.

10.A.1a Organize and display data using pictures, tallies, tables, charts or bar graphs.

10.A.1b Answer questions and make predictions based on given data.

B. Formulate questions, design data collection methods, gather and analyze data and communicate findings.

10.B.1b Collect, organize and describe data using pictures, tallies, tables, charts or bar graphs.

10.B.1c Analyze data, draw conclusions and communicate the results.

Illinois Learning Standards, Science, State Goal 13: Understand the relationships among science, technology and society in historical and contemporary contexts.

A. Know and apply the accepted practices of science.

13.A.1c Explain how knowledge can be gained by careful observation.

B. Know and apply concepts that describe the interaction between science, technology and society.

13.B.1a Explain the uses of common scientific instruments (e.g., ruler, thermometer, balance, probe, computer).

13.B.1b Explain how using measuring tools improves the accuracy of estimates.

13.B.1e Demonstrate ways to reduce, reuse and recycle materials.

Illinois Learning Standards, Social Science, State Goal 14: Understand political systems with an emphasis on the United States.

C. Understand election processes and responsibilities of citizens.

14.C.1 Identify concepts of responsible citizenship including respect for the law, patriotism, civility and working with others.

D. Understand the roles and influences of individuals and interest groups in the political systems of Illinois, the United States and other nations.

14.D.1 Identify the roles of civic leaders (e.g., elected leaders, public service leaders).

Illinois Learning Standards, Social Science, State Goal 16: Understand events, trends, individuals and movements shaping the history of Illinois, the United States and other nations.

A. Apply the skills of historical analysis and interpretation.

16.A.1a Explain the difference between past, present and future time; place themselves in time.

16.A.1b Ask historical questions and seek out answers from historical sources (e.g., myths, biographies, stories, old photographs, artwork, other visual or electronic sources).

B. Understand the development of significant political events.

16.B.1a Identify key individuals and events in the development of the local community (e.g., Founders days, names of parks, streets, public buildings).

C. Understand the development of economic systems.

16.C.1b (US) Explain how the economy of the students' local community has changed over time.

16.C.1a (W) Identify how people and groups in the past made economic choices (e.g., crops to plant, products to make, products to trade) to survive and improve their lives.

D. Understand Illinois, United States and world social history.

16.D.1 (US) Describe key figures and organizations (e.g., fraternal/civic organizations, public service groups, community leaders) in the social history of the local community.

E. Understand Illinois, United States and world environmental history.

16.E.1 (US) Describe how the local environment has changed over time.

Illinois Learning Standards, Social Science, State Goal 17: Understand world geography and the effects of geography on society, with an emphasis on the United States.

A. Locate, describe and explain places, regions and features on the Earth.

17.A.1a Identify physical characteristics of places, both local and global (e.g., locations, roads, regions, bodies of water).

C. Understand relationships between geographic factors and society.

17.C.1a Identify ways people depend on and interact with the physical environment (e.g., farming, fishing, hydroelectric power).

17.C.1b Identify opportunities and constraints of the physical environment.

D. Understand the historical significance of geography.

17.D.1 Identify changes in geographic characteristics of a local region (e.g., town, community).

Illinois Learning Standards, Social Science, State Goal 18: Understand social systems, with an emphasis on the United States.

B. Understand the roles and interactions of individuals and groups in society.

18.B.1a Compare the roles of individuals in group situations.