Volume 2 Number 1

©The Author(s) 2000

Implementing the Project Approach in Part-time Early Childhood Education Programs

Abstract

This paper explores both the benefits and the difficulties of using the Project Approach in part-time early childhood education programs. Teachers of three different types of part-time programs share their experiences one year after taking a one-credit course in the Project Approach. The teachers' responses are organized by topic as follows: (1) curriculum, (2) assessment, (3) parent involvement, (4) time and space management, (5) lesson plans, and (6) program quality. The article notes that one year after initial training in the Project Approach, the teachers in these three part-day programs remain enthusiastic about the approach and have been fairly consistent in including it in their curriculum. They value the approach because it lends direction to their lesson planning, involves parents, helps with collection of samples for assessment, challenges children with diverse abilities, and provides for a more well-rounded "hands-on" curriculum.

Introduction

In my experience, teachers of part-time early childhood education programs often dismiss the possibility of trying the Project Approach in their classrooms because they believe that it will be impossible to implement given their existing classroom structure. Their concerns center around the lack of daily teacher contact with the children, the inability of children to work together given the discontinuities in their schedules of attendance, short class days, and the difficulty involved in managing multiple projects in space that is shared by two or more groups of children. It is possible that teachers of part-time programs do not always see the possibilities for successful implementation of this approach because they have always seen it presented as it functions in a full-time program. Hearing the stories of part-time programs that have successfully begun to implement the Project Approach may prove to be helpful in this regard.

In the spring of 1999, I offered to teach a one-credit-hour class on the Project Approach on-site at a child care center in Princeton, Illinois, a small town in north central Illinois. I was delighted on the first night of class to find that the members of this class included teachers from three types of part-time early childhood programs. With great interest, I watched, listened, and documented the experiences of implementing the Project Approach that these teachers shared during our weekly class meetings. I was curious to see whether their experiences would support my earlier claim that doing project work provides continuity to programs in which children do not attend full time, or in which children follow irregular attendance patterns (Beneke, 1998).

The teachers completed their first project as a requirement of the one-credit class. At the time, I was pleased with the overwhelmingly positive response to their experience of introducing project work in their teaching. However, I wondered whether their enthusiasm would fade as time distanced them from the support offered by their fellow students and instructor. I wondered whether these teachers of part-time programs would find project work to be as useful as have many teachers of full-day programs. So it was with great curiosity that I recently visited each of these teachers in their respective classrooms and interviewed them about their response to project work one year after their initial training and first implementation of the approach. I asked them to share both the benefits and the obstacles to implementing projects in their program, and I also asked them to offer advice about getting started in implementing the Project Approach to teachers of part-time programs. My hope is that their comments will allay some of those concerns that seem to deter teachers of part-time programs from trying the Project Approach. In addition, this article contains the comments of the administrator of two of the programs. For the sake of discussion, I have organized their responses under the following headings: curriculum, assessment, parent involvement, time and space management, lesson plans, and program quality.

The Three Programs

Gingerbread House Nursery School

Jan Whitlock, Mary Stone, and Julie Brown are the three teachers at Gingerbread House Nursery School in Princeton, Illinois. This private preschool has served two generations in this small community. Forty children ages 3-5 attend the program on either a two- or three-day pattern (see Table 1). Class sizes range from 13 to 18, grouping is multi-age, and children attend for approximately 2-1/2 hours per session. All three teachers work on a part-time basis and share the same classroom.

Malden Early Childhood Special Education Program

Kathy Bankes teaches in a multi-age cross-categorical early childhood special education program at an elementary school in Malden, Illinois. The children in her class have been identified as having a significant delay (at least one year) in one or more areas of development. Children in her class attend either four mornings or four afternoons per week (see Table 1). A maximum of 10 children may be enrolled in each class. One day per week is available to Kathy for home visits, professional development, and classroom preparation. Her assistant teacher was also a member of the one-credit Project Approach class, but she has since resigned from the school. Renee H. is currently the aide in Kathy's classroom.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gingerbread House Nursery School Teacher/Child Attendance, Planning, and Portfolio Collection Patterns |

|||||

| AM | Group A Lead Teacher: Mary Teacher: Julie Assistant: Sheila Planner: Mary |

Group B Lead Teacher: Mary Teacher: Jan Planner: Mary |

Group A Lead Teacher: Julie Teacher: Mary Assistant: Sheila Planner: Julie |

Group B Lead Teacher: Jan Mary Planner: Julie |

Group A Lead Teacher: Jan Teacher: Julie Assistant: Mary Planner: Jan |

| PM | Group C Lead Teacher: Mary Teacher: Julie |

Group C Lead Teacher: Julie Teacher: Mary Assistant: Sheila |

Group C Lead Teacher: Jan Teacher: Julie Assistant: Carla Assistant: Lisa |

||

Malden Early Childhood Special Education Teacher/Child Attendance Patterns |

|||||

| AM | Group A Teacher: Kathy Assistant: Renee H. |

Group A Teacher: Kathy Assistant: Renee H. |

Group A Teacher: Kathy Assistant: Renee H. |

Group A Teacher: Kathy Assistant: Renee H. |

Preparation and Home Visits No child attendance |

| PM | Group B Teacher: Kathy Assistant: Renee H. |

Group B Teacher: Kathy Assistant: Renee H. |

Group B Teacher: Kathy Assistant: Renee H. |

Group B Teacher: Kathy Assistant: Renee H. |

Preparation and Home Visits No child attendance |

Malden Prekindergarten At-Risk Teacher/Child Attendance Patterns |

|||||

| AM | Teachers: Renee C. Assistant: Penny Class A |

Teachers: Renee C. Assistant: Penny Class A |

Teacher: Renee C. Assistant: Penny Class A |

Teacher: Renee C. Assistant: Penny Class A |

Preparation and Home Visits No child attendance |

| PM | Teacher: Renee C. Assistant: Penny Class B |

Teacher: Renee C. Assistant: Penny Class B |

Teacher: Renee C. Assistant: Penny Class B |

Teacher: Renee C. Assistant: Penny Class B |

Preparation and Home Visits No child attendance |

Malden Prekindergarten At-Risk Program

Renee Carlson teaches a multi-age prekindergarten at-risk program in the same building with Kathy Bankes. Her students also attend either four mornings or four afternoons per week, but her maximum enrollment is 15 per class. Children are identified for Renee's class by any of a number of developmental or environmental criteria that indicate that they could be at-risk for future school failure. Like Kathy, Renee has one day per week for home visits, professional development, and classroom preparation. Her assistant teacher, Penny, was also a member of the one-credit class on the Project Approach.

Deb Dalton is the administrator of the early childhood programs at Malden public schools. Deb was formerly a teacher in both early childhood special education and prekindergarten at-risk classrooms. She took part in a one-credit course on the Work Sampling System (Meisels et al., 1994) also attended by her teachers.

Curriculum

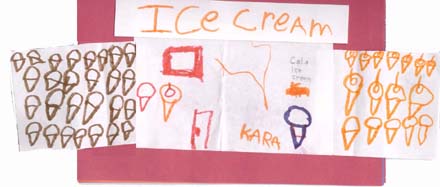

All three of the Gingerbread House teachers continue to be very enthusiastic about project work and were pleased to share information and documentation of a long-term project on the community that they recently completed. Their display revealed highly individualized and creative work by the children, as well as an understanding of many of the businesses and services that make up a community (Figs. 1 & 2). In discussing the way their teaching has changed, Mary explained:

It seemed we used to do a theme like "flowers," and for that week we'd have to do an art project about flowers. We'd have to find the book about flowers. And we might talk about them a little bit. Now we're doing more in-depth study. It's more concrete and more hands-on. We say, "Okay, we're going to plant flowers, and we're going to draw the flowers." For example, last semester, we planted Paper White bulbs. And every day the kids drew them, and they measured. And every day they couldn't wait to come in and measure how high they had gotten.

Figure 1. A piece of the Community Project wall display

depicting the "weigh thing" at the recycling center.

Figure 1. A piece of the Community Project wall display

depicting the "weigh thing" at the recycling center.  Figure 2. A child's representation of the local

ice cream parlor from the Community Project wall display.

Figure 2. A child's representation of the local

ice cream parlor from the Community Project wall display.

Mary shared her belief that the most helpful thing about project work is the contribution it makes to planning, "I think it's easier mainly because you have a goal—to see, first of all, what knowledge the children have, where their interests are, and then once you know where they want to go, it's easier to plan along those lines." Planning is based on the children's interests. One way the teachers pick up on the children's interest is by listening to what the children say, for example, "if they were still asking questions, or if they ask for materials." Mary explained that they have learned to shift the focus of their lesson plans to match the children's interests:

We could start out the week talking about the postman, but if they didn't get into the postman, and they were really interested in something else, it doesn't take a long time to change and get the information that they want. It's not set in stone—what we're going to do.

Project work has also influenced these teachers to include more science in their curriculum. Mary said, "I guess when we first started to do this, we realized that we weren't doing as much science as we thought we were. So now we've really picked up on the science."

Selecting a common overall topic of study for all four groups of children who use their classroom setting has helped these teachers to create a context that unites the children in their programs, despite the discontinuities created by varying schedules and combinations of teachers. This practice eliminates the concern that teachers of part-time programs may have about planning and implementing projects for more than one classroom at one time. Individual classes of children may be interested in different aspects of the project, but these interests generally complement one another and contribute to the experiences of all the children. Mary added, "I find, myself, that it almost has to be a topic that I'm somewhat interested in, too, or I can't get my enthusiasm across to them."

In their respective classrooms at Malden Elementary School, Renee and Kathy also typically select one topic that is investigated by both the morning and the afternoon classes in their programs. This strategy helps them to plan experiences and collect resources for both the morning and the afternoon classes that meet in each of their rooms. Recently, Renee and Kathy have selected the farm as a topic of investigation that has been shared by their two classrooms. This topic is natural for investigation because the Malden school sits along the edge of a cornfield where the children often see tractors and combines. One of the fathers of a child in Renee's class brought a tractor, a combine (Fig. 3), and a semi to class over a period of several weeks, and Kathy's class was able to take advantage of the wonderful opportunity to explore and draw these farm implements along with Renee's class. The two classes also took two field trips together to the local John Deere implement dealer and to a local farm where they explored a hay loft and saw many animals and grain bins. Kathy explained that they did their field trips together, but then "each room sort of did their own thing" to develop the project in their own classroom.

Figure 3. Children from Malden school look at a combine.

Figure 3. Children from Malden school look at a combine.

Like the teachers from Gingerbread House, the two Malden teachers of part-time programs see the firsthand exploration as one of the biggest changes in the way they teach. When asked how their curriculum differed from what they would have done before they learned how to implement the Project Approach, Kathy replied, "We wouldn't have done as many field trips and seen things firsthand. It would have been more of an intellectual thing, rather than the kids actually doing."

As an administrator, Deb Dalton is very pleased with the effect of the Project Approach on her school. When asked how she thinks the teachers' study of project work has affected their teaching, she answered:

I think it's made them think of what level the children are on and where they are taking the kids. I think the webbing does that a lot. Instead of cute themes, they really have to look at where the kids are and what they're doing, what they are interested in. And then they have to figure out how to teach it. They can't find that [ready-made] in a book. [In this process], they've had the kids do things that you don't often think about young children doing. For example, they had two of the kids in the Farm Project do a tally of their favorite farm animals. And the kids did it as a team.

Deb really likes the Project Approach because it serves children with diverse abilities: "It really stretches some of them. And yet, it also allows the child who is not functioning as well, like some of the children in our early childhood special education class, to produce something and to pull on their language abilities."

Deb believes that teachers who use the Project Approach do more work than they would if they were using a traditional curriculum. In the typical early childhood curriculum, more reliance is placed on books:

You know, you can buy a book that says, "101 Things to Do with Teddy Bears." With this [project work], they've got to plan field trips, they've got to be talking to people. They've got to figure out what's hands on [that the children can explore]. They have to bring in the stuff that the kids use to create—make things available to the kids beyond papers with the directions for a fingerplay.

Assessment

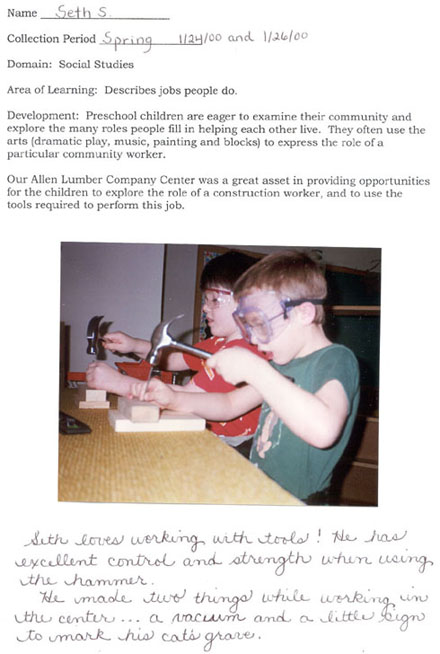

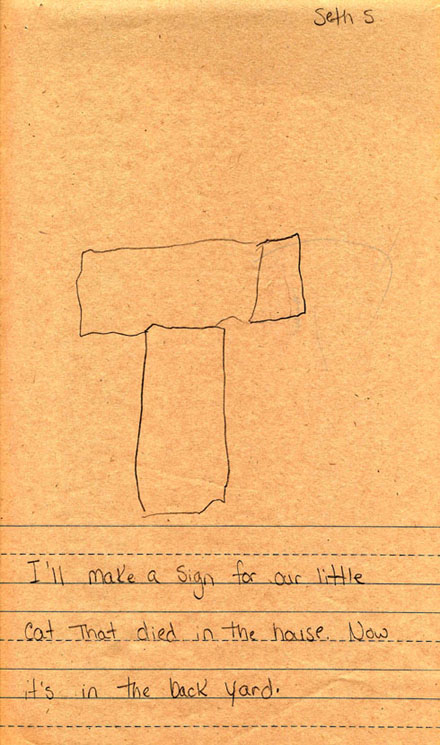

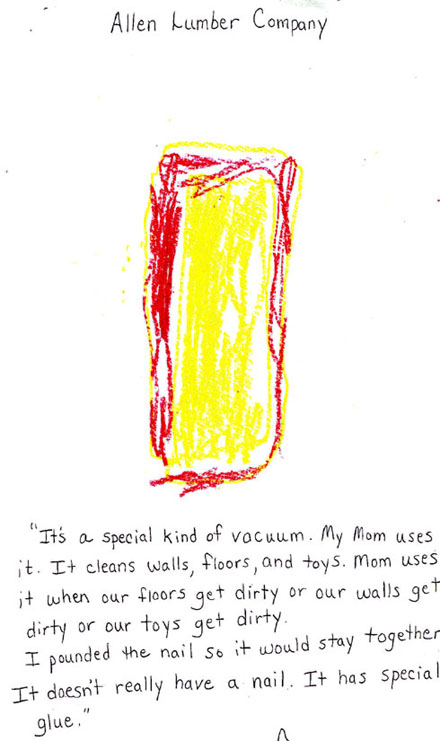

As more and more part-time programs begin to adopt systematic authentic assessment practices, identifying ways to collect samples has become increasingly important. Teachers of children who attend part-time programs often have more than twice the number of children to assess than teachers of similarly aged children in full-day programs. For example, the three teachers at Gingerbread House have 45 children to assess at the end of each collection period. It was very clear in talking with these teachers that they have found project work useful in providing samples for assessment. In fact, they observed that providing samples for documentation is one of the most useful things about the Project Approach. Julie observed that since implementing the Project Approach, "We do more documentation than we used to." Jan had previously taken a one-credit course on using the Work Sampling System. Work sampling is a system for authentic assessment that includes a checklist, portfolio, and narrative summary report (Meisels et al., 1994). She has shared what she learned with Mary and Julie, and together they have designed their own Core Item sheets for portfolio collection. They were eager to share examples of project work that they had collected for the children's portfolios. For example, Mary brought out social studies samples produced as a result of a trip to the lumber store that took place during the Community Project. The accompanying Core Item sheet summarizes the learning that is demonstrated in the two samples (Fig. 4). In one sample, a child whose cat had recently died had drawn a grave marker for the cat and then built the marker out of wood, using his two-dimensional plan as a guide (Fig. 5). He also built a model of a vacuum cleaner and then drew it (Fig. 6).

Figure 4. This Core Item sheet summarizes the learning

that is demonstrated in two work samples.

Figure 4. This Core Item sheet summarizes the learning

that is demonstrated in two work samples.  Figure 5. A child whose cat had recently died had drawn a grave marker for the cat and

then built the marker out of wood, using his two-dimensional plan as a guide.

Figure 5. A child whose cat had recently died had drawn a grave marker for the cat and

then built the marker out of wood, using his two-dimensional plan as a guide.  Figure 6. A child built a model of a vacuum cleaner and then drew it.

Figure 6. A child built a model of a vacuum cleaner and then drew it.

Teamwork appears to be a key ingredient in the successful implementation of the Project Approach and documentation in this program where children and teachers are present on variable schedules. The Gingerbread House teachers handle the discontinuities in staffing and children's attendance by sharing a list of the documentation that is needed. Mary explained their approach this way:

I do the Monday/Wednesday/Friday morning class, and Julie takes the afternoon class, and Jan takes the Tuesday/Thursday morning class, so that, really, I'm more in tune with the morning class, because I do their portfolios. But, we always leave a running list of what we're looking for, so that, for example, if Jan's not here one day, we can get the samples that she needs.

These teachers are very comfortable with sharing the role of planner, lead teacher, assistant, and documenter. As Mary put it, "Our schedules may look complicated, but it works well for us."

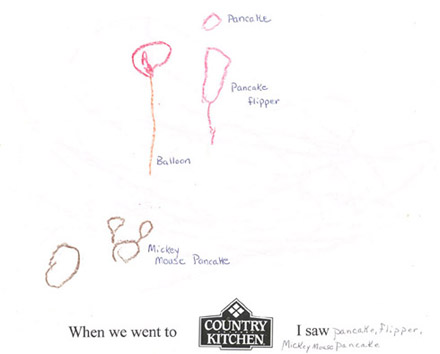

The importance of drawing in project work and the insight it provides into a child's understanding are valued by all three of these teachers. As part of their Community Project, the Gingerbread House children took a field trip to the local Country Kitchen restaurant. Mary, Jan, and Julie showed me how the children's field sketches reflected what they had noticed and what had been important to them during their trip. For example, one boy's sketch included the pancake flipper from the kitchen, the balloons that were given out, and the Mickey Mouse pancakes they were served (Figs. 7 & 8).

Figure 7. The children took a field trip to a restaurant

and ordered Mickey Mouse pancakes.

Figure 7. The children took a field trip to a restaurant

and ordered Mickey Mouse pancakes.  Figure 8. This field sketch shows what one child noticed during a field trip to a restaurant.

Figure 8. This field sketch shows what one child noticed during a field trip to a restaurant.

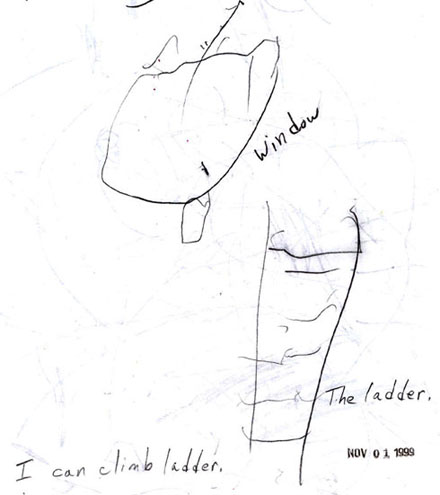

Kathy has been particularly impressed with the drawings that her students have produced in the process of project work. In the past, she has had difficulty motivating the children in her class to draw on their own. Her students typically are delayed at least one year and often have multiple impairments. She shared a drawing of the combine by a 5-year-old girl, who drew a picture of the ladder and the window of the combine during the Farm Project (Fig. 9). Prior to this experience, Kathy had not seen any recognizable shapes in this child's drawings. Putting the drawing in the context of a project helps the teacher to recognize what the child is attempting to draw.

Figure 9. A 5-year-old girl drew a picture of the ladder

and the window of the combine during the Farm Project.

Figure 9. A 5-year-old girl drew a picture of the ladder

and the window of the combine during the Farm Project.

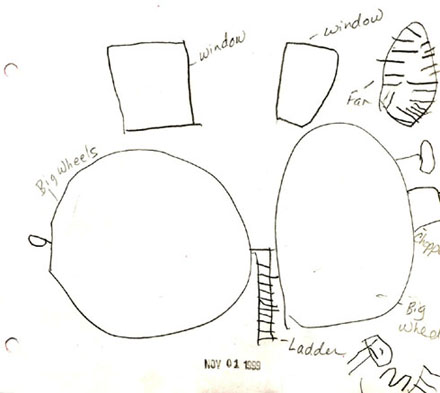

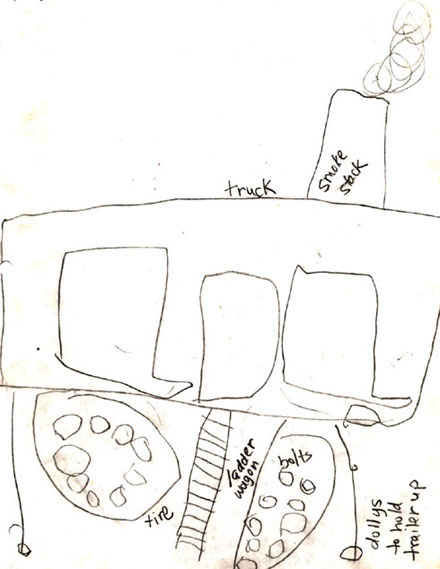

Renee finds the drawings that children produce during project work helpful for demonstrating children's growth and understanding. For example, she showed me drawings of the combine by one little boy on November 1 (Time #1) (Fig. 10) and contrasted them with his drawing of a semi on November 9 (Time #2) (Fig. 11). In the first drawing, he was interested in many of the parts of the combine, but they were not enclosed or connected into a whole. In the second drawing, the little boy was able to include many parts, and he was able to convey information about how they fit together into a whole truck.

Figure 10. A child's drawing of a combine on November 1 (Time #1).

Figure 10. A child's drawing of a combine on November 1 (Time #1).  Figure 11. A later drawing by the same child of a semi on November 9 (Time #2).

Figure 11. A later drawing by the same child of a semi on November 9 (Time #2).

Parent Involvement

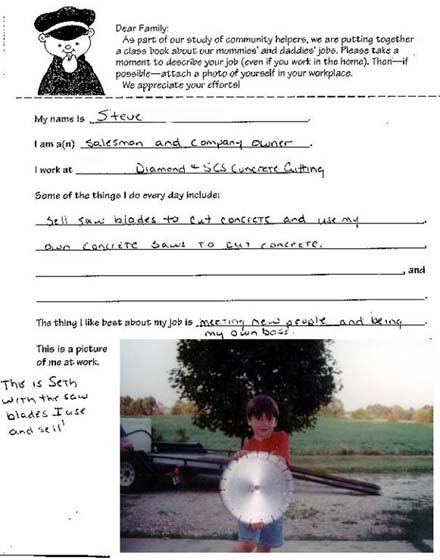

The challenge of parent involvement is similar to the challenge of assessment for teachers of children in part-time programs in the sense that there are simply more parents to involve than there would be in a typical full-time program. The Gingerbread House teachers have been very impressed with the involvement of their students' parents in project work. For example, in their recent Community Project, parents were sent an optional sheet on which they could describe their job. The teachers were surprised at the number and quality of the responses they received (Fig. 12).The teachers indicated their feeling that when parents are kept aware of the ongoing project, a better home-school connection is formed. They saw this connection in the Community Project where they noted that parents were "really supportive. They were interested."

Figure 12. A father filled in an optional sheet

sent home as part of the Community Project.

Figure 12. A father filled in an optional sheet

sent home as part of the Community Project.

Renee has a concern that it is sometimes "hard for the parent to understand the project until it's all done—until you have a project display board to show them," and you can say, "we've done this, this, and this." She sometimes sends a "week in preview" letter home to the parents, but this approach is more difficult with the Project Approach because she's not always sure what will interest the children. On the positive side, parents are invited to help out when the children go on field trips; consequently, the increased number of field trips that the Malden early childhood students have been taking have translated into more parent contacts.

Deb Dalton, the administrator of the Malden programs, finds that the memory books that Renee and Kathy make are really valuable to parents. These are simply bound, laminated books that contain the drawings the children have made and photographs that were taken during a project. For example, both Kathy and Renee have memory books about the combine and the semi for their classes. These books are kept out in the hall all year, and parents, as well as other children and staff at the school, love to look at them when they visit the school.

Deb says that it has not been costly for her teachers to implement the Project Approach because so many of the parents have donated items. She used the current project in Renee's classroom on the grocery store and a past project on the post office as examples: "Parents brought in everything for the grocery store, and parents either brought in or they got from the grocery store, or [from] recycling, everything the children used for the Post Office Project."

Time and Space Management

All the individuals that I interviewed identified some aspect of time as an obstacle to project work. However, in each case, these statements were tempered with statements about the benefits of the approach that seem to justify the time spent. For example, Julie, Jan, and Mary agree that if the children are not interested in what's taking place in school, the time spent in school is less satisfying and a "waste of time" for both the children and the teachers. Consequently, even though they say that it takes a lot of time to prepare for and document project work, they feel that in the long run, it is a better use of their time. Authentic assessment and project work are so intertwined in the practice of these three teachers that their comments regarding obstacles were centered on the time it takes to develop the skills for managing children's portfolios.

Kathy noted that project work is "very time-consuming" in terms of "gathering up and finding materials and setting up field trips." On the other hand, she added, "time-consuming is good. It seems like your whole focus is on the topic, and you're really involved in it." Reflecting about the concerns of other teachers of part-time programs who believe that it will not work to include project work in their part-time programs, Kathy observed:

Until I actually tried, I think I might have said the same things too, but when I see what these children can do and how involved they get ... they're really, really interested in it. And being a half-day program, [to make it work] you just stretch things out. It takes longer.

Kathy is sometimes frustrated about the time available during the year to finish an in-depth project. Referring to the Farm Project, she said that she felt as if "we could've spent another month at least on it, because we had some that were interested in farm machinery, and they would have done more, I think, if we would have had time." The beginning of the long winter vacation caused them to end the project.

Renee and Kathy sometimes find it frustrating to complete a project, given the half-day schedule. Children attend her program from 8:30 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. or from 12:00 p.m. to 2:30 p.m. Project work often is deferred due to other valuable experiences, such as 45-minute physical education classes and regularly scheduled visits to the school library. These teachers have to think of ways to keep project interest and momentum up. Often, they can accomplish this goal by simply reminding the children involved. For example, a boy in Renee's class had been particularly interested in the cash register on their field trip to the grocery store. When they returned from the store, he began to construct a model of the cash register for their classroom grocery store. At the end of class, they saved the partially completed construction and a Polaroid photograph they had taken of the actual cash register at the store. Almost a week later, they interested him in resuming work on the cash register by showing him the construction and photograph and saying, "remember when you were working on this?" He may also have been interested in resuming work on the construction because he could see that it was needed as a prop for the class grocery store that was under construction in the dramatic play area.

Deb describes the way Renee and Kathy manage the shared space:

If one child has made something, like a cash register, in the morning class, and the other kids come in in the afternoon and say, "What's that?," then they just say, "that's a cash register that the kids in the morning made," and they just incorporate it into their play. And there have been some times when they've maybe added to it or painted some more on it. They just seem to think it's their project, whether it's the morning or the afternoon class.

Jan, Mary, and Julie had similar observations. When asked, they could not think of a time when the children ever had a problem sharing their space with the constructions produced by children from other sections. Julie explained that "when kids would come on Tuesday, and somebody on Monday had already started something, they would finish it, and the first child would come back on Wednesday and they would not be offended that this person on Tuesday had worked on their project. There has never been a problem with that." On only a few occasions, there have been children who have worked on a special construction that they wanted the teachers to set aside for them until the next class meeting, but the teachers did not see these requests as problematic. "The other kids knew that, that was theirs, and they couldn't bother it."

Lesson Plans

Julie, Mary, and Jan operate as a team in many of the administrative duties of Gingerbread House, as well as in the teaching duties. Each teacher creates the lesson plans for designated days of the week (see Table 1). Plans are made on a week-by-week basis. Because they are each so intimately involved with the life of the current project, they do not find it difficult to plan for the coming week. They allow each other the flexibility to make changes in the plans based on the interests of the children in their individual classes.

Renee and Kathy are in a somewhat different situation because they are required to submit their plans to a school administrator. However, their administrator has given them the flexibility to respond to the interests of the children in their classes. "Deb is fine with it if we write project work in [a section of] our lesson plans, but some other administrators might not be. They want to know exactly what you're doing." Renee believes this flexibility is allowed because "Deb sees what we do, and she took the [work sampling] class, so she has a good idea of what we're doing and understands. She is very supportive." When asked about her expectations that teachers will follow their plans as written, Deb explained that she sees the teachers' lesson plans as a projection of where the curriculum might go during the week, but "they may or may not have done what's on them [the plans]." She sees lesson plans as a way of thinking about what might happen and planning for the possibilities, but she doesn't believe teachers should be bound by them: "You don't have to be on page one when it says page one. No teacher should, not even in high school."

Program Quality

When asked to reflect on how the Project Approach has affected the quality of their programs, the teachers of all three part-time classrooms were decidedly positive. Mary, Jan, and Julie believe that project work has made their program "more substantial." In explaining their reasoning, Mary stated, "We're not doing all of the teaching. They [the children] are teaching each other. It seems that we are letting them take more responsibility. I feel that the quality of our program has definitely gone up." They agree that they had a good program before, but according to Julie, "This is just better. They come up with some of the most intelligent things! It's just unbelievable to me what kids this age can do and think." Mary agreed and added, "I think doing project work makes you a better listener."

Kathy and Renee are also positive about the effect of the Project Approach on their part-day program. They feel that it challenges the children in their classrooms and enables the teachers to assess children's ability to apply knowledge and skills in a natural context. They believe that by documenting and sharing the project work of the children, others in their community have been able to see the potential of young children to do meaningful work:

We presented to the school board, and they were just amazed. One response was that they couldn't believe these were 3- and 4-year-olds doing this work. I showed them the project we did on the post office, and the things they drew in the [memory] book, and the mailbox the kids created. They were just surprised that students this young were doing that kind of work.

Conclusions

One year after initial training in the Project Approach, the teachers in these three part-day programs remain enthusiastic about the approach and have been fairly consistent in including it in their curriculum. Although they have occasional difficulty finding the time to do project work on a consistent, day-to-day basis, or for as many weeks as they might wish, they have few other frustrations with using the approach. On the whole, they appear to see the Project Approach as an enhancement to the quality of their teaching and to their students' learning. They value the approach because it lends direction to their lesson planning, involves parents, helps with collection of samples for assessment, challenges children with diverse abilities, and provides for a more well-rounded "hands-on" curriculum. Large portions of the afternoons in many full-day programs are often taken up with lunch, naptime, and outdoor play, so the amount of time available to some part-day programs for project work may be more comparable than it might seem at first glance.

The potential of rich topics to interest and unite multiple classrooms may be one reason that the Project Approach works so successfully in these part-time programs. The teachers were able to follow the interests of the different groups of children in different aspects of a topic. The products produced by following these aspects enhanced the shared play environment. Had each group in an environment shared by two or more part-day programs been investigating a different topic, the approach might not have been as successful.

The teachers interviewed here were teaching part-day classes that met at least two days per week, and most met three or four days per week. They felt that the children in their classes met frequently enough to work well together on the project. However, it seems likely that a class that meets only one day per week would not have the same success. On the other hand, it may be that we, as adults, do not give children enough credit for having the desire and ability to maintain interest in a topic over time.

Similarly, it may be that when we doubt children's ability to share the construction of the products of a project with other children whom they never see, we are imposing our own adult sense of competition and territoriality on them. Perhaps the need to impress others with their individual performance may be less important to young children than is the need to develop a rich play environment by building on each other's efforts to construct props. It was clear in talking to teachers from all three of these part-day classrooms that sharing space for construction of project work was not a problem.

The grouping of the children in these classes may also have contributed to the successful implementation of the Project Approach. Multi-age grouping was used in all three of these programs. The older or more developmentally advanced students were able to maintain interest in the topic, whereas a homogeneous group of younger children might not have maintained interest in the topic given the discontinuities in scheduling.

Administrative support and flexibility in lesson plan requirements were evident in the two public school classrooms, while the teachers who shared the private preschool classroom, in essence, were the administration and consequently could provide each other with support and flexibility. Support and flexibility for the implementation of the Project Approach are key ingredients for successful implementation of the approach in a part-day, as well as a full-day, program.

It was apparent that the teachers of the three part-day programs value project work because of its propensity to produce products that could be used for authentic assessment purposes. In programs such as these, where teachers have more children to assess than they would likely have in a full-day program, this propensity proved very helpful. Prior training in authentic assessment practices probably contributed to their recognition of this aspect of the Project Approach.

The teachers who have shared their classrooms here all began this new approach to teaching together with classroom teaching partners and with colleagues. They made a commitment to support one another and to see their first project through. This team approach may also have contributed to their success. They were all quick to say that they struggled in their first projects, but they found, after completing one project, that implementing projects became easier. They felt that the effort required to learn the approach was well worth it.

References

Beneke, Sallee. (1998). Rearview mirror: Reflections on a preschool car project. Champaign, IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education. ED 424 977.

Meisels, S. J., Jablon, J. R., Marsden, D. B., Dichtelmiller, M. L., Dorfman, A. B., & Steele, D. M. (1994). An overview: The work sampling system. Ann Arbor, MI: Rebus Planning Associates.

Author Information

Sallee Beneke is an instructor in the department of Early Childhood Education and the director of the Early Childhood Education Center at Illinois Valley Community College in Oglesby, Illinois (http://www.ivcc.edu/ecec/About.html).

She has previously worked as a master teacher, prekindergarten at-risk teacher, early childhood special education teacher, and day care director. She is author of Rearview Mirror: Reflections on a Preschool Car Project, and coauthor of Windows on Learning and Teacher Materials for Windows on Learning with Judy Helm and Kathy Steinheimer.

Sallee Beneke

Early Childhood Education

Illinois Valley Community College

815 North Orlando Smith Ave.

Oglesby, IL 61348

Telephone: 815-224-0218

Email: beneke@ivcc.edu