From Themes to Projects

Abstract

Many teachers who begin to implement the Project Approach are familiar with a learning center or theme approach to teaching. Often there are some important differences to become aware of. Projects are especially valuable for children in undertaking in-depth study of real-world topics. This paper presents the reflections of several teachers on their experiences moving from the use of a theme approach in their classrooms to using the Project Approach. The paper is presented in two parts. First there is a description of how a project on shoes undertaken by a kindergarten class might unfold, based on a synthesis of several teachers’ accounts of how they proceeded with such a project. The description serves as an example of the potential of a project for the in-depth study of a topic. The second part of the paper is a commentary, interwoven with the narrative description of the project, and draws on the work of different teachers who have also carried out projects on the topic of shoes. This commentary, which features the different possibilities that may occur for teachers in different locations and working with different ages of children, also discusses a few of the challenges commonly experienced by teachers beginning to do projects, particularly the distinctions between projects and themes.

Introduction

This paper presents the reflections of several teachers on their experiences moving from the use of a theme approach in their classrooms to using the Project Approach. Some of these teachers were doing their first projects, while others had been working this way for several years. The paper is presented in two parts. First there is a description of how a project on shoes undertaken by a kindergarten class might unfold. This description is a synthesis based on several teachers’ accounts of how they proceeded with a project on the topic of shoes and is used as an example to show the potential of a project for the in-depth study of a topic.

The second part is a commentary, drawing on the work of different teachers who have also carried out projects on the topic of shoes. This commentary is interwoven with the narrative of the project and features the different possibilities that may occur for teachers in different locations and working with different ages of children. As part of the commentary, a few of the challenges commonly experienced by teachers beginning to do projects are offered, especially their comments about the distinctions between projects and themes.

Projects on Shoes

The topic of "shoes" arose in discussion with the children because it was the beginning of the school year and several of them were wearing new shoes. The shoes had many interesting features: some lit up, some made noises, some had laces with different patterns and colors. The teacher and her assistant thought of many possible directions in which the children’s interests might develop through a study of shoes. They brainstormed ideas and represented where the study might lead in a topic web.

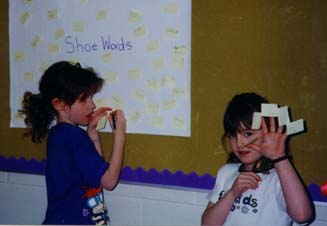

Second-grade children adding words to a collection of ideas for a topic web.

Second-grade children adding words to a collection of ideas for a topic web.

Commentary

The preliminary planning that accompanies much successful project work involves the preparation of the mind of the teacher for the possibilities that could arise from the children’s study of the topic. It is not the kind of objectives-driven planning that characterizes much direct instruction, where the objectives can be operationalized and prespecified in considerable detail. Instead, planning for project work involves the imaginative anticipation of the prior experience and level of interest that might reasonably be expected from a given class of children. The teacher can make a personal topic web of ideas and information that an investigation of the topic might include. She can discuss possibilities for field work, investigations, and representations with co-workers. A teacher who has done these things before the work gets underway can be mentally ready to gauge the children’s experience and interest and is likely to be receptive to the many different possibilities that might arise in the course of the project.

Phase 1: Getting Started

The children in the class talked about their shoes and their experiences buying shoes. They began to wonder about shoes and raise questions. A list of questions was begun and added to throughout the first week of the project. The children painted and drew pictures of shoes and of their experiences buying shoes. The children were encouraged to ask their parents, friends, and neighbors for any kinds of shoes they might contribute to the class shoe collection for the study. The teacher brought in some shoes from her 16-year-old daughter’s closet and added these to the dramatic play corner.

The class set up a simple shoe store in the dramatic play area and tried on the different shoes there. The parents were informed of the topic of study and were invited to discuss shoes with their children. They were also invited to share with the class any special knowledge they might have about shoes. At the end of the first week, the teacher arranged for a child in the class to bring in his baby brother to show them his first pair of "walking" shoes.

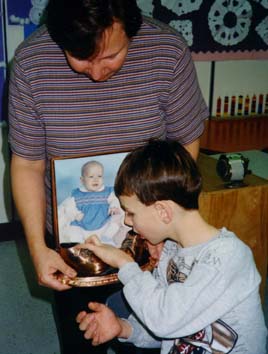

A child examining a pair of bronzed baby shoes.

A child examining a pair of bronzed baby shoes.

Commentary

The process of encouraging children to tell personal true stories about their experiences with shoes is not as simple as it sounds. Here is an account of the experience of one second-grade teacher, Margaret E., who had been teaching through traditional themes for many years until this first attempt at a project. Her first plan to have the children tell stories about their experiences might have led to very constrained efforts on the part of the children. Here is how she described what she was going to do:

I may hold my shoe in my hand and tell a story about the day I could not find my shoe. I may ask the students to hold up their shoe and tell a story about the day they lost their shoe. I may ask the students to get a partner and share a funny story about their shoes.

Instead, because this teacher was taking a course in the Project Approach at the time, her plans were discussed with the class and modified accordingly. Many "lost shoe" stories would limit the number of other kinds of shoe stories the children could tell. The word "funny" in the second sentence would again limit the freedom of the children to share their experiences, whatever these might be. Instead, Margaret E. wrote about her experience with the children as follows:

I started the project with a simple story about the time I lost my shoe. I took off my shoe and held it in my hand as I told my story. Before I finished my story, I could sense that students wanted to tell me a shoe story, so I asked, "Does anyone have a true shoe story to tell the class?" About half the class (13) put up their hands. I thought I would listen to as many as I could, without having the rest of the class getting bored. My first thought about this storytelling session was that the students would all tell a "lost shoe story." After about 20 minutes, my fears changed to excitement. My students told the most interesting, diverse, funny, sad, and totally awesome shoe stories. Here are a few of them:

- Erika told a shoe story about learning to tie her shoe. Her mother would show her every day how to tie her shoes, but she didn’t get it. Then one day she went in the living room by herself. She tied her shoes. She had a big smile on her face when she told this story.

- David told a story about the kinds of shoes he wore in Chile. He described the leather. He said he might be able to bring a pair of these shoes to school for us to look at. We said "wonderful."

- Ryan told a story about the day he tried roller blading in the house. He was roller blading down the hall making black marks. He got in trouble with his mom.

- Joelle told a story about the day her house burned down last month. All her shoes were burned in the fire. She had a hard time telling this story, so I helped her.

- Shelby told a story about the time she got her new shoes. She wanted shoes like the ones that the Spice Girls wear. She got her wish.

- Stephanie told a story about the tap shoes that Spanish dancers wear. Her family is from Costa Rica. She may be able to show us the tap shoes.

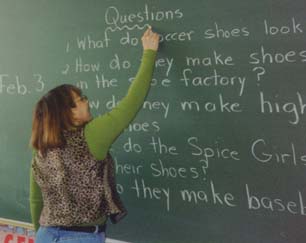

Many teachers find the process of developing lists of questions with children very difficult, as well. Sometimes it helps to have a particular pair of shoes for the children to think about. It also helps to model the process of "wondering" prior to formulating a question. In the case of the second-grade teacher quoted above, there was a pair of antique shoes from her collection that she was able to bring in to show the children. Here is list of questions from the same class of second-grade children, with the teacher’s account of the process of eliciting them through modeling her own wondering:

I held up a pair of antique lady’s and men’s shoes. I told the students two things that I wondered about with respect to these shoes. I told them that I wondered who had worn these shoes, and I wondered who had made these shoes. Then I asked the students what they wondered about and recorded it on chart paper.

- Marcel wondered if they would fit him.

- Kyla wondered if they would stink.

- Megan wondered what they would feel like.

- Ryan wondered if they have any gum stuck on the bottom.

- Kaylyn wondered how long it would take to make these shoes.

- Kaitie wondered how much they cost.

- Brandon wondered if they would fit me.

- Shelby wondered how long the shoelaces were.

- Martin wondered where I got them from.

- David wondered what they were made of.

The teacher records children’s questions about shoes.

The teacher records children’s questions about shoes.

Some of these questions would be answered at the central location in the classroom where the shoes would be on display, available for the children to investigate for themselves.

Phase 2: Developing the Project

The teacher and the children talked about what they could do to get answers to their questions about shoes. The questions included: What are shoes made of? Where are shoes made? How much do they cost? How do you know what size you wear?

As the children began to discuss money, they talked about what the storekeepers did with the money people paid when they bought shoes. Some thought the salespersons gave it to poor people, others thought they took it home for their pay, and some thought the boss kept it all. The variety of predicted answers to questions heightened the children’s curiosity and desire to find out more details about what went on in a shoe store. The teacher arranged a trip to a family shoe store in their city. The children worked for a whole week to prepare for the trip. They decided what parts of the store needed to be investigated, and who would take responsibility for drawing what parts of the store and for asking which questions of the boss and of the salespersons. The field work was planned to get the information needed to make a more elaborate shoe store in the classroom upon their return.

Five groups formed around the children’s special interests. The children were interested in investigating:

- The cash register, how many shoes are sold in a day, and the amount of money collected each day.

- How the shoes are displayed in the shop windows and presented for customers’ viewing in the store.

- The storeroom, and how the shoe boxes are arranged (e.g., men/women/children, sizes, dress/sport, etc.).

- The shoe salesperson’s responsibilities and activities.

- The different kinds of shoes available.

- Sizes, colors, and numbers of shoes in stock.

- Where the shoes came from, where they are delivered, and the frequencies of deliveries.

- The shoe collection brought by children to the class in terms of their materials, their special functions, and style, model, and manufactures’ names.

The teacher and her assistant worked in turn with each group to talk about the questions they wanted to ask and what they wanted to find out. The teachers helped the children develop ways to record the information to be gathered at the store.

The teacher contacted the personnel in the shoe store in advance to prepare them for the visit by explaining the expectations she had for the field experience. She outlined the questions the children wanted them to answer and described the drawings planned, the observations the children wanted to make of them at work, and the items the children wanted to examine closely.

When the big day arrived, the three people at the shoe store spent about 20 minutes with each group of children. The children returned to school with a great deal to think about! The teacher and her assistant led discussions in large and small groups to debrief the children about the visit.

Each group told the whole class about the information the group had acquired. Then the children set out to build a shoe store in their classroom. Groups and individual children found out what they needed to know to make what they wanted to add to the shoe store. Throughout the next 3 weeks, the teacher talked to each group about its progress, and the children listened to each other’s ideas and made suggestions.

The children worked on making models of cars to get to the store. They made a bird in a cage and a television set like the ones they had seen in the store. They made catalogs for their store’s shoes. They marked the shoe boxes so they would know which kinds of shoes were in the boxes. Some children made money for the little cash register the teacher provided. They made a shoe chart so that shoppers in their store could tell their shoe sizes. They worked on a book to tell new shop workers how to sell shoes. They made a wooden bench for children to sit on while waiting to be served. In some cases, several versions of these things were made because children wanted to be personally involved in particular contributions to the store. In particular, children made many shoe catalogs! A Turkish guest worker also helped two children from her country to use their own language in the context of the project by producing a Turkish version of a shoe catalog and posting advertising and directional signs in Turkish.

During this period of investigating and representing the items they wanted to put in their shoe store, the children invited several visitors to their classroom. Another teacher in the school was a dancer and showed her tap shoes and her special jazz dancing shoes. One parent visitor showed her special shoes for bicycle racing. A grandfather of one of the children had repaired shoes in his work and was able to tell the children about how shoes are made and what they are made of. With this knowledgeable man’s help, the children were able to examine the parts of a shoe: the leather, thread, tacks, and glue used in shoe construction. Various other kinds of sports shoes were shown to the children by older siblings, and their special features were discussed: ice skates, roller blades, Doc Martens, ski boots, fishing waders, golf shoes with cleats, wooden shoes from the Netherlands, ballet slippers, cowboy boots from Texas, and soccer shoes.

During the field visit, the children had been able to watch the process of selling a pair of shoes to a customer. They noted the steps in the process from the salesman’s and the customer’s points of view. The children were able to use these steps in the dramatization of the sale and purchase of shoes in their own shoe store. They took pride in showing several pairs of shoes to prospective buyers, measuring their feet, interviewing them as to the kind of shoe they wanted and the color and price they wanted to pay. Then children concluded the sale and put the unsold shoes back in their boxes and back on the storage shelves.

The children who made the dollar bills set up a bank so that their money could be used in the purchase of shoes in the store. A number line was provided to help those children who wished to use it to count out the money they wanted to spend. Prices were added to the information on the shoe boxes.

Commentary

In the second phase of a project, the work tends to become much more investigative and diversified than in the first phase. The directions the project takes often reflect the variety of sources of information the teacher finds among parents, family members, and people and businesses in the local community. In other shoe project descriptions, the following stories were told by teachers about the resources they discovered for their projects.

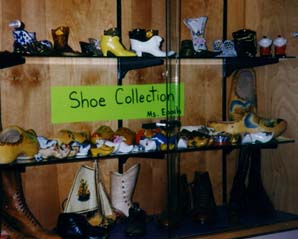

One teacher developed a project on shoes with her second-grade class. A teacher of an older class in the same school had written a children’s book called Sneakers: The Shoes We Choose. This teacher, Robert Young, came as a visiting expert to the class and brought the largest professional basketball player’s shoe (that of Shaquille O’Neal) and the smallest baby’s shoe he could find, for contrast. The basketball player’s shoe was a size 22, triple E! Margaret E., the second-grade teacher quoted earlier, had inherited some antique shoes and a shoe ornament collection containing 300 items. She had bone china shoes, glass shoes, bronze shoes, stained glass shoes, wooden shoes, miniature shoes, and hundreds of shoes from different countries: Holland, India, Germany, France, England, Scotland, Canada, the United States, and Japan.

A collection of antique shoes and shoe ornaments.

A collection of antique shoes and shoe ornaments.

In one kindergarten class I visited, the father of one of the children was a lawyer. He helped the children understand the importance of shoe print evidence at the site of a crime in finding criminals. In another class, one of the parents had worked for some years in a shoe store and was able to tell the children about how a shoe store operates, as well as a good deal of information about different kinds of shoes. In Margaret E.’s classroom in northwestern Alberta, Canada, a group of children went out on snow shoes. Before they went, they drew what they remembered snow shoes looked like; later they were able to draw snow shoes from observation in the classroom. Elsewhere children learned about the shoes sled dogs wear to protect their foot pads from becoming rough and icy, and about how, until recently, women in the Yukon would gather with friends to sew hundreds of these little felt booties for the winter.

Snow shoes.

Snow shoes.  A child doing a field sketch of snow shoes.

A child doing a field sketch of snow shoes.

In the second phase of the project on shoes, the teacher, Margaret E., tried to increase the quality of the children’s work and their commitment to their own choices and the development of their own interests and ideas:

When I teach using systematic instruction with the Thematic Approach, all the children do all the activities at the same time. They try to finish as many as I have presented for that class time. If they finish the art project or worksheet, I give them the next one. The students follow the instructions, and if everything goes as planned, I should have 26 similar art projects or worksheets. They think they have to do everything that I have presented even though I have stressed that I want quality, not quantity. Now, with the Project Approach, I am listing a lot of project choices to untrain my class and myself. I need to let my class experience that they have many alternatives to choose from. I would like them to try the ones that interest them and work on them to a high standard. I would like them to apply their own skills at their own independent level.

Making choices does seem to help children feel competent and become more committed to completing their work to a standard that will be satisfying both to them and their teacher. For teachers beginning to work with projects, giving children choices can be a challenging step, and choice is something that children learn to exercise with increasing responsibility. Dot Schuler, an experienced teacher at implementing the Project Approach, writes:

Even now, I always feel apprehensive about what they will choose, but being allowed to make these choices with guidance from their teacher is one of the main reasons why children enjoy their project work so much. (Dot Schuler, PROJECTS-L Listserv, January 23, 1999)

Children themselves can also discuss the process and value of making choices in their work. Some benefits of making choices were expressed by a group of first-grade children to their teacher as follows:

Carrie: When you work on projects you choose what to do. So usually you choose something you can do, or maybe something that you think you can do, so you can get to work.

Teacher: But maybe you’ll need help if it’s something you only think you can do?

Diana: Well, not really. You chose to do that because you thought you could do it, so you must have some ideas of what to do.

Carrie: And if the first one doesn’t work, the next idea might.

James: And if you make the choice, you try harder to make it work. (Leskiw, 1998, p. 127)

Phase 3: Concluding the Project

After several weeks, the children became interested in new kinds of play. They wanted to explore the bus travel that had begun during the shoe project as some customers came to town to buy shoes using the local transit system. At this time, the teacher arranged an opportunity for the parents to come to the school to visit the children’s shoe store and see what had been learned in the process of developing the children’s interests in shoe store construction and play. The parents had the opportunity to buy shoes in the store and be served by their children.

The parents were able to look at the children’s drawings and paintings. They were able to read the documentation of the project, including the word labels and captions written by children and teachers on the representational work, and the photographs taken throughout the project to record the high points and various aspects of the children’s learning. Among the skills applied by the children were counting; measuring; using technical vocabulary; color, shape, and size recognition; and interviewing and other social skills. The knowledge children had gained concerned the processes of designing, manufacturing, and selling shoes, and much information about the variety of materials used in making various kinds of shoes and different parts of shoes. Children also appreciated the working of a store and the interdependence of the several different people involved in enabling people to wear something as basic as shoes. The parents who were able to take part in the final sharing of the work were left in no doubt that valuable in-depth learning had taken place over the 8 weeks of the life of the project.

Kaitie’s drawing of snow shoes from observation is much more detailed than her drawing from memory.

Kaitie’s drawing of snow shoes from observation is much more detailed than her drawing from memory.

Commentary

The third phase of a project often involves a review and evaluation of the work that has been done. It can also involve arranging a culminating event to share the highlights of the work with parents or another class of children. This phase also serves as a debriefing for the children on the detailed work accomplished. The children often show good recall and understanding in their presentations and deliver their explanations with considerable confidence.

One second-grade teacher was invited to talk about her shoe project at a "school-to-work" conference in the local city. She was to be one of a team of teachers from the school. She decided to take a child to tell the story of the school project. The 7-year-old showed overhead transparencies of the work and talked informatively and with confidence about the work the class had done. The teacher said she could not have given a more impressive account if she had done it herself.

Many teachers who begin to implement the Project Approach are familiar with a learning center or theme approach to teaching. Often there are some important differences to become aware of. Projects are especially valuable for the children in undertaking in-depth study of real-world topics. However, they are not the only approaches to teaching. The second-grade teacher, Margaret E., writes about such distinctions in her journal:

When I started a theme, for example on cats, my whole room would be transformed into a cat room. I would be the expert on the topic, I would set up the room before the theme would start, I would get all the materials ready, I would plan every center, make every worksheet that I was going to use, find every art project that I was going to make with the children. My own knowledge would be the starting point for the study on cats. Everything would be preplanned. I would pull out my boxes on cats and use the same stuff year after year.

As I can see now, the thematic approach would be a good way to start a unit on something quite foreign to grade 2 students, for example Australian wildlife or the planets. I think another time for thematic work would be when you need to present a short study on a part of the curriculum or review on a unit, like money.

Teachers doing projects for the first time talked about the challenge of responsive and ongoing planning that includes frequent negotiations with the children. They also commented on the importance of being a model for the children of dispositions that enhance learning. For example, children become curious, interested, and committed to their investigations and representations as they see such interest and commitment modeled around them. The teacher has an important role as a model, and children in older classes who may come and work with the younger children as part of a project can also model desirable dispositions.

One first-grade teacher completed a case study of a project for her master’s thesis. In it she wrote about her experience with this way of teaching, making special reference to her modeling role: "I knew, too, that it was essential for me to model questions, expectations, and standards without prescribing or limiting the ideas the children might offer" (Leskiw, 1998, pp. 20-21). This kind of modeling is also important to develop children’s interest. Interest is important for its capacity to energize project work. Interest may already be present in children in relation to a topic of study, like "shoes," but for many children, interest will develop following lively discussion about the topic in the classroom.

The topic itself, "shoes," is only as interesting as the questions that can be investigated—as what it is possible to find out about shoes. The teacher’s role is critical in formulating the questions. I once had a teacher tell me about how she had tried to interest a group of children in the topic of shoes, but that they had resisted any attempt to focus their attention on the topic. It might have been that the particular group of children was more interested in almost anything else, but their resistance also may have been due to the teacher’s inexperience at developing interest among the children. One teacher, Margaret B., with many years of experience with projects, refers to her role as "spokesperson for reality." In this role, the teacher interprets reality in terms of the opportunities it offers for investigation. Children who have little experience with project work are not aware of how thoroughly topics can be investigated. They cannot become interested in what they know nothing of. Teachers who only have experience with preplanned themes likewise must discover the richness of the investigative potential of project work.

In this article, I have presented an account of a project on shoes. Among the descriptions of the phases of development that this project took, I have included commentary based on teachers’ accounts of their project work. There has been discussion of the distinctions between themes and projects and references to the challenges faced by teachers beginning to do this kind of work with children. Particularly, the relationship between teacher and children is likely to be changed through project work. Project work can provide a view of a child that most clearly reveals to the teacher what the child is capable of. As one teacher writes about her grade 1 children, "The way I perceive students has changed somewhat. My students are capable of completing any task they undertake. I spend more time developing their strengths, rather than on focusing on their deficiencies. This has meant a change in the way I report student progress to parents. I must still complete a report card, but I do so with many anecdotes directly relating to work completed rather than percentages or marks. As well, a monthly portfolio is sent home to parents" (Leskiw, 1998, pp. 144-145).

As Dot Schuler writes, "Gradually, and continually, I am learning not to doubt the potential capabilities of children when they become involved in their project work" (personal communication, 1999).

Note: Pictures for this article were contributed by teacher Margaret Epoch and her second-grade students, but the activities shown could be undertaken in shoe projects with children from kindergarten to third grade.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the following teachers for their contributions to the information here on the projects undertaken in classrooms and for the reflections and comments freely given in journals, personal communications, and phone interviews: Margaret Brooks, Margaret Epoch, Candy Ganzel, Lorraine Leskiw, Dianne Roth, and Dot Schuler, whose classrooms are located, respectively, in Alberta, Canada; Indiana; Oregon; and Illinois.

References

Leskiw, Lorraine. (1998). A study of the engagement of children’s minds. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Alberta.

For More Information

Katz, Lilian G., & Chard, Sylvia C. (1989). Engaging children’s minds: The Project Approach. Norton, NJ: Ablex. ED 407 074. Project Approach Web Site (http://www.ualberta.ca/~schard/projects.htm)

PROJECTS-L Listserv (http://ecap.crc.illinois.edu/listserv/projec-l.html)

Author Information

Sylvia C. Chard is associate professor in the department of elementary education at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. She previously served as the head of the department of early childhood education and principal lecturer at the College of St. Paul and St. Mary in Cheltenham, England. Sylvia has taught at the preschool, elementary, and high school levels in England. She is coauthor with Lilian G. Katz of Engaging Children’s Minds: The Project Approach (Ablex, 1989), and has written several articles and two Practical Guides to the Project Approach (Book 1 & Book 2, Scholastic, 1998). She has taught numerous courses and workshops on the Project Approach in Canada, the United States, Japan, Korea, and Europe; and she co-owns and manages an electronic discussion group (PROJECTS-L), is designing online courses, and continues to develop a Web site (http://www.ualberta.ca/~schard/projects.htm) to help teachers share their experiences of project work in classrooms. Sylvia’s research is in teacher development and the implementation of the Project Approach in schools.

Sylvia C. Chard

Associate Professor of Early Childhood Education

Director of the Child Study Centre

Department of Elementary Education

551 Education Building South

Edmonton, Alberta

Canada T6G 2G5

Telephone: 403-492-4273 Ext. 236

Fax: 403-437-7987

Email: Sylvia.Chard@ualberta.ca