View in Chinese (PDF) HomeJournal ContentsIssue Contents

Volume 10 Number 1

©The Author(s) 2008

Appreciating Diversity through Children's Stories and Language Development

Abstract

Appreciation of diversity begins in our classrooms with the children we know and interact with on a daily basis. Each child has a unique history—a story that gives us insights when we interact, plan our classroom community, and design our instruction. Children who have a primary language other than English have stories that they can communicate to others in a variety of ways. By becoming aware of children's histories, we focus on them as people first and language learners second. Adults can learn children's histories through children's play, dramatics, and artwork. This article describes some of what the author has learned through her own young children, who have English as a second language, and discusses her children's growth and development in ways that make what she has learned applicable to all children.

Introduction

My husband and I adopted our two young children from Guatemala, where we have been involved in several projects over the past 13 years. We adopted our daughter Yoselin when she was 2 years old, and we adopted our daughter Flor de María when she was 4 years old. Yoselin joined our family understanding only her first language, Spanish, but she did not speak much because of her age. Flor de María spoke only Spanish, but she also communicated with us through drawing, pantomiming, and play.

Understanding Guatemalan culture has helped us better understand Yoselin and Flor de María by providing us with a context for viewing their challenges and successes. Guatemala is a very beautiful and poor country where many people live in absolute poverty—poverty where basic needs are not met. With the poverty, there is hunger, disease, and illiteracy, and many babies and children are relinquished for adoption. Older children who are adopted or have recently immigrated to the United States from Guatemala have stories that often involve neglect caused by poor living conditions, and many children also feel the pain of leaving family members behind. Guatemalan families speak Mayan languages or Spanish, so not only do adopted children have to adjust to another culture, but they are also required to quickly learn a new language in which to communicate. As teachers, helping children be successful requires not only teaching them English but understanding the stories of their pasts as well. Understanding a child's stories provides a window into the child's emotions, behaviors, and thinking.

I am an education professor at the University of Northern Colorado, and working with Flor de María's learning of English came at a time when I was involved in a grant project to help university faculty teach preservice teachers how to work with children who have English as a second language. As part of the grant, we were involved in seminars, held discussions on readings, and traveled to Mexico and El Paso, Texas. My involvement with the grant, in addition to working with Flor, taught me many things that I now share with my university students. This article describes some of what I have learned and now teach my preservice students so that they can help children who have English as a second language and share an appreciation for the difficulties encountered by children acquiring a second language.

Children's Stories

Diversity begins in our classrooms with the children we know and interact with on a daily basis. Sarah, who likes to water the plants because she takes care of the garden at home; Juan, who likes to be a tiger when feeling shy in order to separate himself from the group; and Andrés, who compassionately hugs all the boys and girls upon their arrival to school—all deserve and long to be part of a caring community. The community we share together can provide strength to individual children and demonstrate tolerance and appreciation of differences.

Each child and family has a unique history—a story that gives us insights when we interact, plan our classroom community, and design our instruction. Children who have a primary language other than English have stories that they can communicate to others in a variety of ways. By becoming aware of children's histories, we focus on them as people first and second-language learners second. This approach allows us to attend to children's language needs while viewing their understanding and use of language within the context of their experiences and all areas of development (Rigg & Allen, 1989).

Adults can learn children's histories through children's artwork, play, and dramatics. Much is being written about children's play and artwork—not only as ways for children to better understand one another, but as wonderful ways in which children can express and communicate their ideas, experiences, and feelings (Thompson, 2005; Schirrmacher, 2002; Jones & Reynolds, 1992).

Art

Children can tell their stories through art, whether in collage, paint, or other media. Illustrations or other artwork can convey thoughts, actions, events, emotions, and experiences that words may not express (Thompson, 2005). For example, when Flor de María first came to live with us, she drew a picture of me carrying her on my back. In Guatemala, it is common for a mother to carry her baby on her back in a shawl until the child is 4 or 5 years of age. The picture reflects Flor's experiences in Guatemala.

Figure 1. Flor drew herself being carried on her mother's back.

The first several months that Flor lived with us, she drew family pictures on a daily basis, and those pictures were her efforts at working through the process of joining a new family and struggling to feel a sense of belonging. At first my husband was drawn very small at the bottom of the page, but as Flor began to develop a safe relationship with him, he moved to the middle of the page. In the illustration below, he is even playing ball with her.

Figure 2. Flor drew a picture of playing ball with her father.

As we work to understand children's stories through their artwork, it is extremely important to ask children to tell about their drawings, because it is easy to interpret something into their work that may not have been intended by the child (Schirrmacher, 2002; Thompson, 2005). At the same time, when they tell us orally about their artwork, we gain additional insight into what they are trying to communicate.

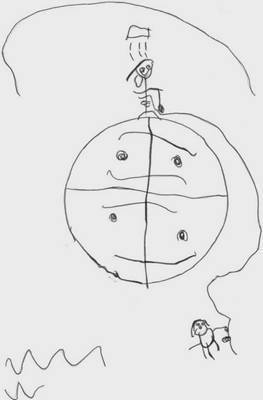

Some of Flor's drawings were intense and complicated. For example, the illustration below communicates her feelings about having to leave a brother behind when she was adopted. Her brother, Jerison, stayed in Guatemala when she came to be with our family because he had a father in Guatemala City who saw him regularly. In this illustration, Flor is at the top of the Earth, her brother is at the bottom, and a cord connects them. There is a rain cloud with rain pouring down on Flor's head to represent her feelings surrounding separation from a brother she loves.

Figure 3. Flor's drawing represents her feelings about being separated from her brother.

Artwork can also provide children with a way to record events and help them make sense of their experiences. This function is particularly significant for children who are taking part in new cultural experiences. "Their paintings, drawings, collages, songs, stories, and constructions reveal what they see and understand about the world around them" (Kieff & Casbergue, 2000, p. 172). For example, Flor made the drawing below when she experienced Christmas for the first time in the United States.

Figure 4. Flor drew this picture during her first Christmas with us.

Play

When focusing specifically on language and play, many theorists, including Piaget (1951) and Vygotsky (1978) state that through play, children develop symbols and symbolic capacities that contribute directly to the development of language and concept formation.

One very important aspect of language and play is that, when playing together, an ELL (English language learner) child and an English-first child can communicate and make adaptations as their play evolves. In a journal I have kept over the past few years, I have recorded language interactions between Flor de María and Yoselin. As they were playing in the bathtub one month after Flor's arrival, the conversation between the two of them went like this:

Yoselin: You got water in my ojo [eye].

Flor: Lo siento [I'm sorry], Yoselin.

During a walk by the river during this same time period, the conversation was like this:

Yoselin: This rock is muy grande [very large]!

Flor: Vamos a [we are going to] lift me up.

When Flor and Yoselin were reading the story of The Three Billy Goats Gruff, the conversation was as follows:

Flor (pointing to goats): Mamá and dos hijos [mama and two sons].

Yoselin: No, just tres [three] goats.

The power of language during play is that it is purposeful and authentic. The interactions are meaningful to the children at the time, and they work together to communicate about what they are involved in (Dudley-Marling & Searle, 1991). The approximations they make when exploring with words in Spanish and English are necessary in developing language and in expressing the concepts they understand and want to communicate. This use and learning of language is powerful and cannot be substituted through the use of word cards or other artificial means.

At school, Flor also adjusts and adapts her language, as do the other children who play with her. They support the socially correct use of her words, even if approximated—but not when the approximations are personal. For example, her preschool teacher said that the boys did not like it when Flor put together phrases such as, "Her don't want to play," in which the pronoun "her" refers to the boys. Actually, this statement was quite an advanced translation of Spanish to English in its implication that Flor understood the concept of pronouns but did not yet recognize gender delineations.

Another example of her use of Spanish language grammar patterns in her English happened during a game of hide-and-seek. She was looking for the boy who was hiding and, upon finding him, happily exclaimed, "I found to you!" Although this sounds awkward in English, the grammar would be entirely correct if translated directly into Spanish. At other times, Flor uses adjectives after the noun, such as when describing her new shoes at school to her friend: "See my new shoes beautiful?" In Spanish, the adjective comes after the noun, so she is quite clever in taking what she knows about one language system and applying this knowledge to another. Flor has acquired a good understanding of how to use language. However, if she were to write this in a story, a teacher might not recognize what was happening and wonder what was going on with her thinking. Children using language the way that Flor does are very successfully transitioning from Spanish to English.

Dramatics

When we first brought Yoselin home, she got up one morning, came downstairs, and pantomimed patting back and forth with both of her hands. It took me a moment to realize that she wanted me to make corn tortillas. After I understood what she was telling me, I got out the masa, and we made them together for breakfast. Flor still acts things out when she is unsure whether or not I understand. Today she wanted a donut at the store. I thought I understood what she wanted, and I asked her if she wanted a donut. Not quite sure if that was the word for what she wanted, Flor drew a circle in the air with her fingers. "Yes, that is a donut," I responded, and she repeated, "donut." In this way, I help her scaffold her language, and we communicate in a way that is satisfying to both of us.

Communicating through gestures is entirely appropriate and an excellent way to add to the wholeness of communication, which is what language is about. A child can act out a story before he or she tries to tell it orally so an adult or another child can help scaffold for meaning. Or perhaps the child can draw the story first, act it out to help the viewer gain an understanding of what has been created, and then try to tell the story orally or through writing.

Vivian Paley is well known for a technique called "storyacting," during which children tell a story to an older child or teacher who is acting as a scribe. The scribe checks with the child throughout the story to make sure he or she understands what is being told and writes it down. Then the child who tells the story selects other children to be characters and props in the story. The young author then directs the acting out of his or her story (Paley, 1990).

Oral Language Development

Oral language develops with reading, writing, and listening in a variety of contexts. Children's reading, writing, and speaking work together simultaneously as children express themselves and make meaning (Dyson, 1993). I have used some of the same reading and writing activities successfully with Flor and Yoselin that I used with my older children at home who have English as their first language.

Each day my husband and I read several books to Flor and Yoselin. Of course they want to hear their favorites over and over, but they also want to hear new, exciting stories yet to be told. After reading a book, Flor loves to hold the book by herself and retell the story to us in her own words. This process is fascinating in that it not only makes her a reader and gives her ownership of the words she tells when creating the story, but if the story is not one she has heard repeatedly, she will make up her own story line based on the pictures in the book. When she does not have the Spanish or English vocabulary to express what she wants to express, she uses the words she does have in unique and interesting ways.

For example, we had just read Big Bad Bruce by Bill Peet (1977) for the first time when Flor told the story to us based on the pictures, improvising with her language. In the story, a witch turns a large bear into a very small bear about the size of a kitten so that the bear can live peacefully with the witch. On one page, when the witch starts to shrink Bruce, there are three images, each a little smaller than the previous one. Flor pointed to the first image and said, "Big," pointed to the second and said, "chiquitín" [little], and then pointed to the third image and said, in a very, very small voice, "chiquitín."

Now that Flor has been with us for a year and read many books repeatedly, she retells the stories fairly accurately. Last night she read aloud Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? written by Bill Martin (1992) and illustrated by Eric Carle. Her language was impressive in that her retelling was based on her new experiences, recent exposure to books, understanding of how Spanish transitions to English, and the new vocabulary she has acquired. She opened the book and read (the actual text is in italics):

Bear, bear,

Brown Bear, Brown Bear,What you look?

What do you see?I look at bird.

I see a red bird looking at me.Bird, bird,

Red Bird, Red Bird,What you look?

What do you see?I look at duck.

I see a yellow duck looking at me.Duck, duck,

Yellow Duck, Yellow Duck,What you look?

What do you see?I see a horse look at me.

I see a blue horse looking at me.Horse, horse,

Blue Horse, Blue Horse,What you look?

What do you see?I see la rana [the frog] look at me.

I see a green frog looking at me.Rana what you look?

Green Frog, Green Frog, What do you see?I see a cat look at me.

I see a purple cat looking at me.Cat, cat,

Purple Cat, Purple Cat,What you look?

What do you see?I look at dog.

I see a white dog looking at me.Dog, dog,

White Dog, White Dog,What you look?

What do you see?I look at oveja [sheep].

I see a black sheep looking at me.Oveja, oveja,

Black Sheep, Black Sheep,What you look?

What do you see?I look at fish.

I see a goldfish looking at me.Fish, fish,

Goldfish, Goldfish,What you look?

What do you see?I look at maestro [teacher].

I see a teacher looking at me. Maestro, maestro,Teacher, Teacher, What you look?

What do you see?I look at niña [girl].

I see children looking at me.Niña, niña, Children, Children,¿Qué ves ahí? [What do you see there?]

What do you see?Bear, bird, rana [frog], duck, horse, oveja [sheep], pez [fish] y maestro [teacher].

We see a brown bear, a red bird, a yellow duck, a blue horse, a green frog, a purple cat, a white dog, a black sheep, a goldfish, and a teacher looking at us. That's what we see.

Flor read the book with expression and for meaning. The pictures provided her with clues as to which animal was coming next. Not knowing the names of colors in Spanish or English, she eliminated the colors of the animals. "What you look?" substituted for "What do you see?" but captured the meaning of the book and was consistent throughout. When Flor got to the frog looking at her, she slipped into Spanish with "rana" [frog]. She did this again for "sheep" and read "oveja." After the sheep page, she was getting tired and words in Spanish became more frequent as she read "pez" for "fish." It was obvious that she knew the word "fish" because she read it in the line above. The word "teacher" was read "maestro"; "girl" was read as "niña"; and "what you look?" became "¿qué ves ahí?"

Another pattern book, The Gingerbread Man by Jim Aylesworth (1998), was not as familiar to her. The following excerpt is what she said as she looked at the pictures:

One a time a pie

Old woman and old man

Look at me a gingerbread man.

Yo [I] feet yo head bake.

Her cook in the oven and smell oh good.

Her run faster and faster.

Cow say, get back.

Run, run her said. I a gingerbread man.

You can't catch me. I a gingerbread man.

Flor started her story with "One a time a pie," which was very knowledgeable and showed that she was developing a story schema where many tales start with "Once upon a time" and have a middle and an ending. She switched to first person to describe the gingerbread man through his voice, saying, "Look at me a gingerbread man. Yo [I] feet yo [I] head bake." This was a good technique for giving the gingerbread man a voice and was again something she had learned since coming to live with us and listening to many books where the characters speak.

Flor uses the pronoun "her" for all people, so when she switched back to first person, she read, "Her cook in the oven and smell oh good. Her run faster and faster." Flor demonstrated that she was beginning to figure out the linguistic code by adding "-er" to "fast" in order to communicate how the gingerbread man was running (Jones & Fuller, 2003). The cow then called to the gingerbread man, telling him to wait so he could eat him, which Flor stated concisely as "Cow say get back." Again, she changed to first person, saying, "Run, run her said. I a gingerbread man. You can't catch me. I a gingerbread man."

Brian Cambourne (1988) wrote about the conditions that need to be in place in order for children to develop oral language. I have found the conditions to be true for children learning a second language as well as for children learning a first language. When children learn language through immersion, the people around them are demonstrating the use of language in meaningful ways. Children also become engaged because of the power that language has when it is used in authentic environments. Our expectations of children and language are important—conveying our expectations that they will learn language results in a self-fulfilling prophecy.

It is also important to understand that children learn language in individualized ways. One child may develop fluency a word at a time, whereas another child might begin speaking in full sentences. Allowing children to learn in their own unique ways gives them the responsibility to be successful.

Perhaps, most importantly, children need many chances to approximate with language in varied situations. When adults respond to children's approximations of language, they give powerful messages to the children about their uses of language. Responding to approximations also provides wonderful opportunities to scaffold children's use of language, taking them to the next level without correcting them.

Conclusion

I draw on these experiences when I teach my education courses. Relating what I have learned from my work with ELL at our university and from my daughters Flor de María and Yoselin and their language development has helped me to understand that language is one piece of a child's larger development. Understanding each child's story helps us to be able to adjust instruction to the child. By understanding individual children and their successes and challenges, we can help children be successful.

When we understand children's experiences, we can design authentic instruction that links new information to what children are experiencing. Our teaching will engage children's minds in learning if it is meaningful and true to their worlds. Children's art, play, and dramatics are a few of the ways that children can be who they need to be and communicate with others.

When we brought Yoselin home to live with us, one of my friends said not to worry about her adjustment—"she was so young she probably would not even realize that her environment had changed." We know this is very untrue. Helping others understand where children are developmentally, how they learn, and the need to celebrate the processes that children go through during their learning of language is important in order for children to learn in a healthy and positive manner.

References

Cambourne, Brian. (1998). The whole story: Natural learning and the acquisition of literacy in the classroom. New York: Scholastic.

Dudley-Marling, Curt, & Searle, Dennis. (1991). When students have time to talk: Creating contexts for learning language. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Dyson, Ann Haas. (1993). Social worlds of children learning to write in an urban primary school. New York: Teachers College Press.

Jones, Elizabeth, & Reynolds, Gretchen. (1992). The play's the thing: Teachers' roles in children's play. New York: Teachers College Press.

Jones, Toni Griego, & Fuller, Mary Lou. (2003). Teaching Hispanic children. Boston: Pearson Education.

Kieff, Judith E., & Casbergue, Renee M. (2000). Playful learning and teaching: Integrating play into preschool and primary programs. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Paley, Vivian Gussin. (1990). The boy who would be a helicopter: The uses of storytelling in the classroom. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Piaget, Jean. (1951). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood (C. Gattegno & F. M. Hodgson, Trans.). New York: Norton.

Rigg, Pat, & Allen, Virginia G. (1989). When they don't all speak English: Integrating the ESL student into the regular classroom. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Schirrmacher, Robert. (2002). Art and creative development for young children (4th ed.). Albany, NY: Delmar.

Thompson, Susan C. (2005). Children as illustrators: Making meaning through art and language. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Children's Books Cited

Aylesworth, Jim. (1998). The gingerbread man (Barbara McClintock, Illus.).New York: Scholastic.

Martin, Jr., Bill. (1992). Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What do you see? (Eric Carle, Illus.). New York: Henry Holt.

Peet, Bill. (1977). Big Bad Bruce. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Author Information

Susan Thompson is a professor of education at the University of Northern Colorado. She coordinates the early childhood program and teaches social studies education courses and graduate courses in multicultural education. Her research interests include social studies, diversity, young children, child abuse and family violence, and high-quality instruction for all children.

Susan Thompson

University of Northern Colorado

Greeley, CO 80634

Telephone: 970-351-2070